America-jin desuka? Nai, Africa-jin desu.

Back in 2009, as I sat at a train station in Kobe, Japan, waiting for my train, a young boy aged about six traveling with his mother sat next to me and asked if I was American. I replied no, that I am African. He said I wasn’t African and must be an American. I reaffirmed that I was African and could not be American, but the next question took me aback. He asked why I was wearing clothes. Surprised, I asked why I shouldn’t wear clothes. He went on to say that Africans don’t wear clothes and he still didn’t believe I was African because I had clothes on. I argued that we wear clothes in Africa, and his mother even joined in the discussion to confirm that people in Africa wear clothes.

Perceptions and misperceptions. Nevertheless, in digesting the boy’s understanding of Africa, I couldn’t help but appreciate the fact that his mental picture of Africa is shaped by the visual representation of the continent in the electronic media. The focus by the global television network on famine, wars, diseases, and other ills that have plagued the continent leaves little or no room to highlight aspects of life remotely appealing to the eyes, especially those of young children growing up in other parts of the world. Disney shows, Teletubbies, and Cartoon Network have no African settings and none emanates from within; hence I cannot fault the little boy’s (mis)understanding of the African continent. In spite of its limitless amount of sunshine, Africa is often termed the “Dark Continent,” and at other times the “Forgotten Continent.”

The year 2020 was remarkable in many ways because the COVID-19 pandemic elicited a global response to a situation in a manner never witnessed before. While we applaud the developed economies for making a COVID-19 vaccine available within a year, this feat has been prompted by the fact that they are directly impacted by the pandemic. The argument that it takes two or more years for a vaccine to be certified fit for humans is no longer tenable, and the reaction to the COVID-19 virus shows that where there is the will, there will always be a way. The sad reflection of this advance in medicine is that malaria has killed millions in Africa over several decades, and the story of a malaria vaccine is still a work in progress. It is therefore evident from the COVID response that if malaria were endemic in the Western world, a malaria vaccine would have been on the shelf 50 or more years ago. This is the plight of Africa.

Education infrastructure varies throughout the world; while high-tech learning environments may be commonplace in the developed world, learning takes place nonetheless in other regions that lack such facilities. Africa boasts of individuals who have excelled professionally in different parts of the world because of the enabling environment, and many more migrate to the West, with a good number dying in the process, to prove themselves in the ever-competitive global labor market. Notable are the diaspora of Africans who are products of an education system that is inherently African and go largely unreported or unknown to the outside world. This brings to the fore the question of equity—global equity where world citizens ought to have a sense of inclusion in world affairs.

From Africa, Wole Soyinka of Nigeria was the first Black man to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1986, followed by Naguib Mahfouz of Egypt in 1988. In the English language teaching and learning field, Africa lacks a figure of global eminence because not much is reported from the continent to the wider global audience, for many reasons. Lack of interest in exploring language-classroom practices in the African continent, dearth of resources, general apathy both within and outside Africa, poor technological infrastructure, and lack of wherewithal for personal and professional development of English teachers account for the under-reporting of Africa in the wider English language teaching (ELT) community.

In addition to formal training, language teacher associations exist all over the world to support the professional development of teachers. The conceptualizations of language teacher associations (LTAs) in the Western and non-Western contexts differ in terms of representations, nature of activities, and relationships with external bodies (Padwad, 2016), but their goals and activities are similar even when these differ in quality. Members of these associations have specialized knowledge and resources which they share toward the achievement of a common goal. Membership of such a body comes with personal and professional benefits such as the development of interpersonal, management, leadership, communication, and time management skills (Bailey, 2002). Similar to what occurs in developed countries, LTAs in developing countries provide teacher training and development opportunities for school teachers. Overall, the common denominator is the annual conference organized by the LTA, which serves as the main professional development activity for its members. Among the big players are TESOL International Association, based in the U.S., and IATEFL in the UK. TESOL International Association’s annual convention draws participants from all over the world and has membership from over 100 countries. Its convention serves as the global “go-to” event where networking opportunities abound for language teachers and the latest research findings and cutting-edge classroom practices are shared.

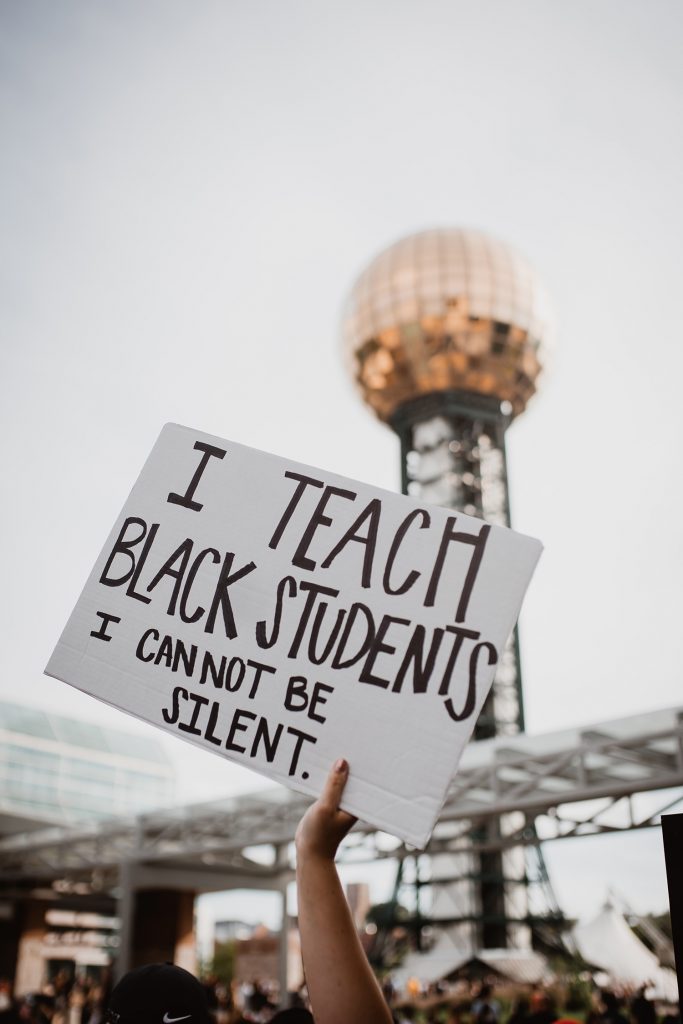

Over the years, African English teachers have not benefited much from these opportunities available only in the international arena. Among the thousands who attend these events annually, only a handful from Africa are sponsored by the U.S. State Department through the Regional English Language Office (RELO) to attend TESOL conventions, while the British Council (BC) supports a few to attend IATEFL conferences in the UK. In all cases, the African teachers participate as attendees, not as presenters with the aim of sharing what English teachers are doing in Africa. This professional news blackout has been persistent over the years, but for how long will it continue? In 2010, I attended the TESOL Convention in Boston and realized only four LTAs in Africa were affiliated with TESOL International Association. A continent comprising 52 countries with only four representative LTAs was simply not good enough. The absence of Africa on the global stage can be attributed to poor national economies, lack of political will by the local education authorities to invest more in teacher education, and at the individual level, the opportunity cost of daily survival instead of investing in the professional development of oneself.

With such a poor showing of Africa at the TESOL Convention in Boston and with no understanding of how LTAs function because this was my first time attending a conference, I wrote an angry email asking the TESOL president at the time to justify why Africa had only four affiliates in such a big international organization. He did respond and outlined the effort by the organization to reach out to the underrepresented regions. Rather than be an armchair critic, I opted to get involved to understand the workings of an LTA, with the sole aim of bringing Africa to the global ELT arena. My journey and involvement with the TESOL Association began at that moment. Subsequently, I went on to form Africa TESOL in 2015, a continental body that would bring English teachers in Africa under one umbrella to ensure they can be not only seen but heard by fellow professionals in and outside Africa. More on the formation of Africa TESOL is documented in Elsheikh and Effiong (2018, p. 74). Africa TESOL is in its fifth year, four successive conferences have been held in four African countries, and in 2020, a virtual symposium was held in August.

The main goal of setting up the continental body was to address the inequity in opportunities for professional development taken for granted by colleagues in more advanced countries. The annual conferences offer a platform for teachers on the continent to share their research findings and classroom practices with other African teachers. The multicultural and multilingual contexts in which these teachers work in Africa make such information sharing more enriching and rewarding for attendees of Africa TESOL conferences. Colleagues and friends of Africa TESOL from Europe and the U.S. offer their support by self-funding trips to these conferences to give workshops, thereby allowing the African teachers to access knowledge that would otherwise be accessible only by attending the big international conferences. Africa TESOL was inaugurated in 2015 with four affiliate countries or LTAs, but it now has 23 affiliates in its fold, and as it continues to add value to what it does, the number will grow. In addition to enhancing research, conducting in-service training for teachers, and sharing experiences and best practices to improve the standard of English language teaching, the leaders of these affiliates also share their challenges (Elsheikh and Effiong, 2018).

As a fledging body, it has its challenges, such as finance, volunteerism, and political bottlenecks. Without a physical secretariat or the financial resources to operate one, Africa TESOL is currently virtual and the leaders of the affiliate LTAs communicate via a WhatsApp group. Another forum on the Telegram app has recently been set up because a WhatsApp group cannot accommodate all our members. The organization has a basic but functional website (http://africatesol.org) and a board of dedicated volunteers charged with steering the organization into the future. Despite the negative impact of the pandemic on all facets of life, Africa TESOL was able to provide a webinar series for its members in 2020 on professional and leadership development. It has expanded its membership base, and members are more engaged than in previous years. It has also engaged in mentoring programs that benefit teachers in Africa. For instance, it collaborated with IATEFL ReSIG (Research Special Interest Group) to mentor 26 teachers from eight African countries who work together to develop contextually appropriate solutions to specific classroom challenges through action research in their different classrooms. Some of the mentees shared their research findings at the 2020 Virtual Symposium.

Africa TESOL in collaboration with EVE (Equal Voices in ELT) is engaged in a female leadership mentoring program to equip female African teachers with the presentation and public speaking skills necessary to present at international conferences and local professional development events. Many of the mentors are friends of Africa TESOL based in Europe and the U.S. who give their time to promote the profession in Africa. In effect, the mentoring programs highlight the work done by these teachers, which is capable of inspiring others and gives them the confidence to become professional conference presenters. It is through such presentations they can share their stories with the wider ELT community. Africa TESOL has also developed a strategic partnership with TransformELT, UK, and Bridge Education Group, USA. Bridge Education Group offers free short professional development courses that help to keep teachers’ skills current and provide fresh ideas for the classroom.

An open-access journal is desirable, to share with the world what goes on in the Africa ELT community and to be accessible to the English teachers in Africa who cannot afford the subscription fees of good international journals. Nevertheless, the future landscape of ELT in Africa will be bright as long as the broad vision of Africa TESOL is maintained and sustained. The challenges are enormous but not insurmountable because where there is the will, there will always be a way. Africa TESOL must not suffer the same fate as malaria.

References

Bailey, K. M. (2002). “What I Learned from Being TESOL President.” In J. Edge (ed.), Continuing Professional Development: Some of Our Perspectives (pp. 32–38). Kent: IATEFL.

Padwad, A. (2016). “The Cultural Roots of Teacher Associations: A case study from India.” ELT Journal, 70(2), 160–169.

Elsheikh, A., and Effiong, O. (2018). “Teacher Development through Language Teacher Associations: Lessons from Africa.” In A. Elsheikh, C. Coombe, and O. Effiong (eds.), The Role of Language Teacher Associations in Professional Development (pp. 71–86). Cham: Springer.

Dr. Okon Effiong is the founder and past president of Africa TESOL. He is currently serving as a board member of TESOL International Association.