Culturally responsive teaching (CRT), a research-based approach that makes meaningful connections between what students learn in school and their cultures, languages, and life experiences, should be a priority for districts in today’s society. Not only is our nation’s population becoming more diverse, but events like the Black Lives Matter movement, the global pandemic, and the shift to more remote learning have all brought further attention to the need for CRT at the K–12 level.

As districts look to deepen and expand their work around the tenets of diversity and inclusion, CRT serves as a foundation that schools can use to build an ecosystem for equity that transcends all the verticals in the workplace. Whether that means learning a student’s first name, embracing his or her bilingual capabilities, or creating district-wide guiding CRT principles for everyone to follow, these are all steps in the right direction.

This article highlights three steps that they can be taking now to either launch a new CRT initiative or improve upon their existing efforts.

We’re All in a Challenging Place

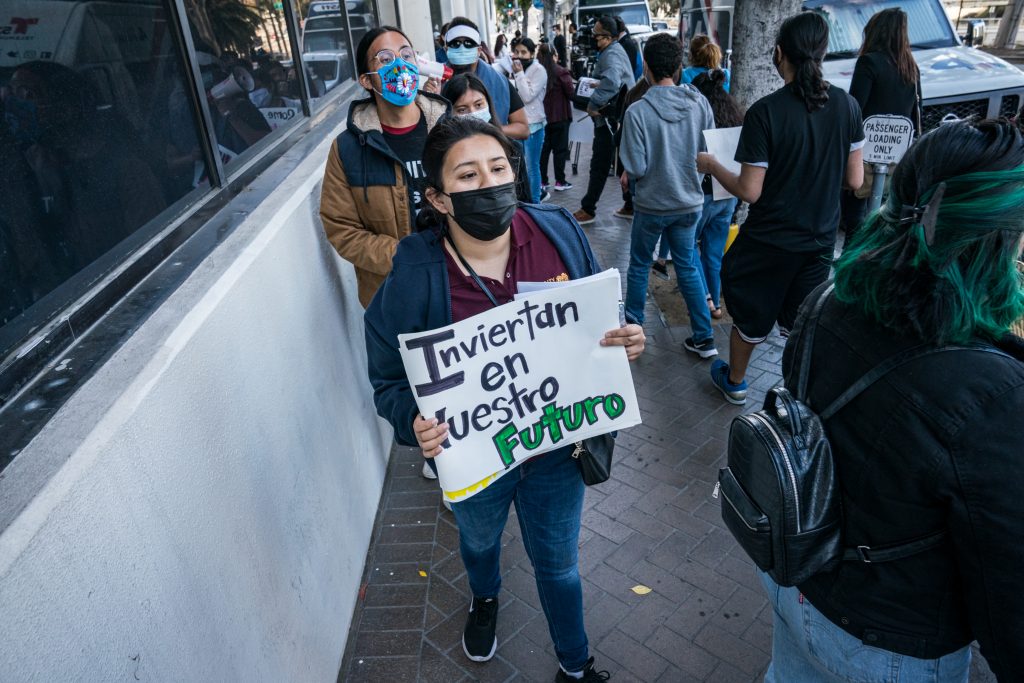

Current events have pushed more districts to think about what they’re doing to develop young minds. These events also show the importance of considering the backgrounds, ethnicities, and beliefs of students as assets to be respected. Essentially, current affairs have highlighted why educators should accept students for who they are instead of viewing students as having a deficit or focusing on who they are not. This is the reason we refer to the learner who is learning English as an emergent bilingual.

We believe that the heritage language a learner knows is an asset and understand that by learning English, the learner is on their way to becoming bilingual. Indeed, the learner could be on their way to becoming multilingual. The point is to focus on what the learner knows as a starting point. With so many students now learning from home, there’s little question that emergent bilingual students who are trying to master the English language can benefit from this asset-model mindset.

These bright young minds no longer have the support of a “live” teacher in the classroom to help them achieve their academic goals. Some students don’t have access to the hardware, software, or Wi-Fi at home that they need to complete their schoolwork. Layer in the lack of exposure to and/or interaction with academic English, and growing language proficiency becomes an even steeper mountain for students to climb.

The Black Lives Matter movement opened the eyes of the average U.S. citizen to the racial inequities that exist in our society. As citizens stood up and took a stand against unfair treatment and police brutality, our educational system began to take a harder look at itself and to seek out ways to create equity and dismantle systemic racism in schools. The question now is, what can educators do in 2021 to support the positive momentum toward equity, justice, and fairness?

Three Steps to an Effective CRT Ecosystem

The COVID-19 virus put a brighter spotlight on equity issues that were already in place long before the global pandemic emerged, particularly in terms of identifying students who weren’t getting the things they needed in order to succeed in school. The push to help individual students succeed has become an even bigger priority because every single student is facing some level of struggle right now—from the first grader who previously worked at or above grade level to the tenth grader who has long struggled with core subjects like English and math.

With its broad brush, the pandemic took a swipe at our entire educational system. As a result, what worked in the past for students simply doesn’t work anymore. It also presented an opportunity to start conversations about how to help all students achieve and attain their educational goals.

The resultant efforts definitely require extra work, particularly when it comes to tackling problems like unconscious bias and systemic racism.

The good news is that there are ways for schools to make strides in this area by developing CRT ecosystems. Here are three course-correcting steps that administrators and teachers can start using now to get on the right path.

Step One: Work to Uncover Unconscious Bias

No teacher wants to be thought of as someone who has a preconceived bias against a specific student (or a group of students), but traditional thinking unfortunately pushes us in this direction, whether we like it or not. Defined as social stereotypes toward certain groups of people, unconscious bias is usually based on the tendency to organize social worlds by categorizing people according to their social or identity groups.1

Knowing this, schools can lay out the framework for a CRT ecosystem by working to uncover, expose, and then eliminate as much unconscious bias as possible. This needs to start at the ground level because even the most advanced CRT plan will fall short if the instructor doesn’t acknowledge his or her own unconscious bias before delivering a lesson.

One place to start is by acknowledging that unconscious bias exists and that it can be eradicated. In terms of emergent bilingual students, we can start by viewing their heritage languages as assets instead of deficits. For example, I’ve heard teachers refer to an emergent bilingual child as “having no language and not knowing anything.” In reality, that student already speaks one language and is on their way to becoming bilingual.

By viewing the heritage language as an asset or even thinking of it as background knowledge, an educator can leverage the first language to help the student learn the second language. Flipping the conversation to the positive includes the teacher as well; they can also be viewed from an asset perspective and focus on being the person who teaches the learner English, which suddenly becomes an honor. This shift will help propel thinking forward in a new and positive way.

In fact, extending this thinking further, we can question the designation of learning English as an intervention. For most of my career, I have heard English learning referred to as part of the tiers of intervention. However, if I view language learning from an asset model, it helps me to see that when learners in other scenarios (the student in China learning English, the dual-immersion student, the person learning at home with an app or a program like Rosetta Stone) begin their language journeys, they are met with praise and enthusiasm. I think that this same sentiment should be afforded to our students who are learning English, even though they have traditionally been relegated to the ranks of intervention students. We can change this point of view by applying the asset-model mindset. The fact is, all students learning a second language are experiencing the opportunity of bilingualism, and it should be praised.

To address the issue of racism and unconscious bias and build an effective CRT ecosystem, schools can start by acknowledging that we each have our own unconscious bias to contend with. If we strive for honest conversations and use the asset-model mindset as our guidepost, we can change our thinking, be more inclusive, and get better results immediately.

Step Two: Develop Guiding Principles

Most school districts have a mission statement, guiding principles, or both. You can either start from scratch or revisit the ones you currently have, which may be found in your English Learner Master Plan or other documents. These guiding principles are designed to be a living, breathing document, meaning they shouldn’t be in a book on a shelf somewhere but instead be a reference point for every decision being made.

If you want to develop guiding principles, we recommend starting by reflecting on your student body. For this, we can learn from what some of our favorite brands do.2 For example, Starbucks refers to customers as “partners,” and they have carefully crafted verbiage describing how the partner should be treated. For a district, we can carefully consider who the learners are, what they’re trying to accomplish, and how we can help them achieve these goals. Be honest with yourself about how you’re serving students and helping them work toward their individual accomplishments (and through their challenges). You can use technology to your advantage during this exercise; having the data about students from the time they stepped onto campus is a big plus.

That data will also help you understand why a student is labeled an emergent bilingual and at what point that label was applied, how many students are at or above grade level, how many of them are designated as special education students, and so forth. Drilling down into this data is the first step. The next step is to get to know your learners better by asking questions about individual students: what was their life like before they started school? What were their parents thinking and feeling? How do they feel knowing that their children are becoming bilingual? How do they feel about learning English?

With this information in hand, you can create some generic yet deep student profiles that, in turn, will help you think creatively about what can be done to support those learners. The more you get to know yourselves and your students, the better the outcome.

When we first built our guiding principles for creating curriculum, we followed the

outline above, which resulted in these:

- Design learning experiences from an asset-based orientation toward learners and learning.

- Design learning experiences in which multilingualism and language variance are valued and seen as resources.

- Design learning experiences in which diverse cultures and identities are valued and seen as resources.

- Design learning experiences that honor and strategically leverage the school–family connection.

These principles might seem standard, even generic. But they inform every single decision we make. One example I often talk about is our work with speech recognition engineers, in which we had the option to use machine learning to push the erroneous notion of “Standard English,” the idea that there is an ideal accent for speaking English.

In reality, we know that English is spoken all over the world and is pronounced based on the heritage language the speaker knows. We had conversations and referred to our guiding principle “Design learning experiences in which multilingualism and language variance are valued and seen as resources,” and we knew that we would not use artificial intelligence to try to create a false sense of a standard accent. Instead, we accept English as it’s spoken by our learners and seek to improve their accuracy with grammar and syntax. We know that pronunciation is subject to heritage language, and as long as a person can make themselves understood, we consider accent variety the spice of life.

We encourage you to re-examine your guiding principles or create new ones. As part of your guiding principles, you’ll also want to include your goals as educators (e.g., to help all learners achieve academic success). And if students aren’t reaching that goal, you will use the guiding principles to help you find solutions to support them.

The good news here is that there is a lot teachers can do to be more inclusive. There are straightforward steps you can take today to help learners feel included. For example, our guiding principle “Design learning experiences in which diverse cultures and identities are valued and seen as resources” can be easily adopted in the classroom—it essentially means to get to know your students. One easy way to do that is to learn their names. For example, I met a teacher once who decided to call a student Sarah because her name, Sarai, was difficult for that teacher to say. She basically refused to say the student’s name, which sent the message to the learner that she was unimportant and that the teacher’s comfort was more important than the student’s.3

Knowing a student’s heritage language and how to say his or her name may sound basic, but research shows that this simple step can significantly reduce school dropout rates.4

This is just one example of a reversable problem that can be solved through strong guiding principles that are reinforced and iterated upon.

Step Three: Put Your Guiding Principles into Action

Your guiding principles will be able to lead your school or district down the path of success and inclusion, if they are put into action, iterated upon, and reviewed regularly. It’s not enough to say you have principles. Much like a company’s mission statement is useless if not upheld by leadership and employees, a district’s CRT ecosystem won’t function properly if its guiding principles aren’t taken seriously.

The principles should also be integrated into every aspect of your institution—from the time you hire a new employee to the procurement of new curriculum to the way teachers interact with students in the classroom and/or online. If you’re starting a new after-school program, for example, consider whether it aligns with the guiding principles and make sure that everyone working in the after-school program knows the guiding principles and adheres to them.

When it comes to new curriculum, think about how the programs are safe, nonjudgmental, and culturally responsive. For example, when Lexia Learning introduced Rosetta Stone English in 2020, it did so with the emergent bilingual student in mind. The program has culturally and ethnically diverse characters who engage with and encourage students throughout their learning journeys as they build the linguistic competence and confidence needed for academic success through academic conversations.

It’s important to involve all departments in this exercise—from the school nurse who treats sick children to the cafeteria employee who feeds them to the librarian who works with them in the media center. Each of these roles is just as important as the individual teacher when it comes to upholding and acting on the guiding CRT principles.

Finally, be sure to revisit these principles on an annual basis to ensure that they continue to reflect the needs of your student body, employees, and changing world environments.

If your school is experiencing a shift in the cultural makeup of its student body, for instance, your existing principles may need to be modified to reflect these changes. A great way to manage this annual task is by assigning it to a group or committee that becomes responsible for making sure the principles are up to date and relevant for the school.

Ready, Set, Go

The learning environment is ripe for change right now, with culturally responsive teaching expected to play a leading role in the online and offline classroom for years to come.

The genie is out of the bottle and isn’t going back in; we all have to stand up and take responsibility for seeing that our diverse student bodies make it over the educational finish line.

Links

https://diversity.ucsf.edu/resources/unconscious-bias

www.fastbusinessplans.com/business-plan-guide/mission-statement-and-guiding-principles.html

www.transact.com/blog/bilingual-name-identity

http://teachingonpurpose.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/Glenz-T.-2014.-The-importance-of-learning-students-names.pdf

Maya Valencia Goodall, MA MEd, and Kristie Shelley, MEd, are both senior directors of emergent bilingual curriculum at Lexia Learning (www.lexialearning.com).

Maya is an entrepreneur and educator dedicated to helping people become bilingual. Her passion exists at the intersection of theory, curriculum design, and practical use in the classroom.

Kristie has spent the last two decades helping bridge the education gap through language and literacy. She’s an educator, entrepreneur, and advocate, elevating educational equity every step of the way.