COVID-19 Impacts Children’s Literacy

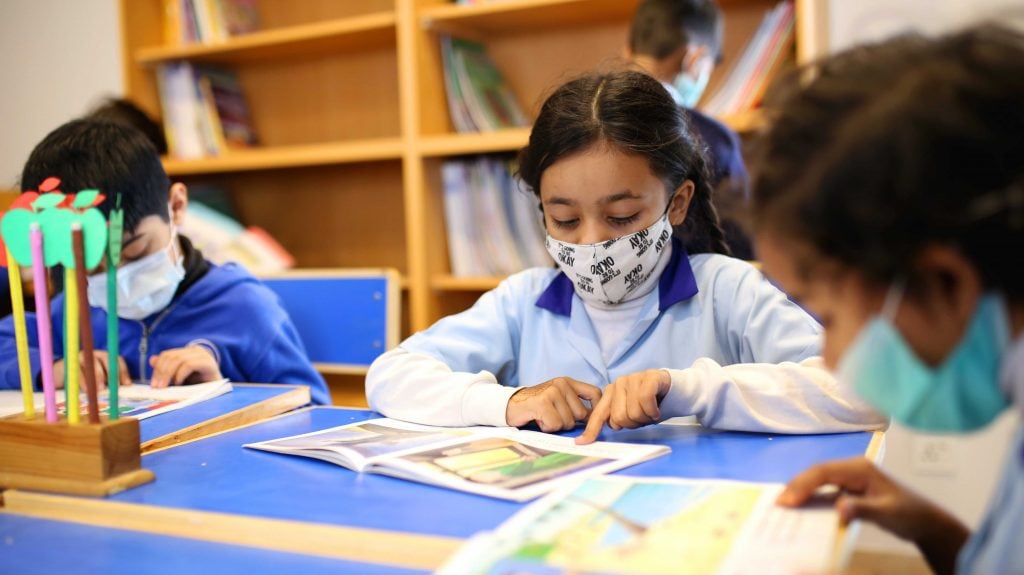

For the past year and a half, instead of heading to the school bus stop and socializing before classes, students across the globe walked over to a device and turned it on to access their virtual classrooms. It was, to say the least, an adjustment for everyone.

The disruption to in-person learning led to losses for students. According to a study from the nonprofit assessment organization NWEA, students across the board lost percentile points in reading and math during the 2020–2021 school year, with Black and Latino students experiencing larger declines than White and Asian students.1 Initiatives designed to stem these losses were critically important.

Beginning in early 2020, the restrictions in response to the COVID-19 crisis required administrators and educators to make dramatic adjustments to almost every aspect of education in order to provide a continuum of learning. It also required Herculean efforts from parents, families, caregivers, and students.

In the face of rapidly changing parameters, Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) and other youth-serving organizations across the nation had to pivot to accommodate the needs of their constituents. As it became clear that in-person learning was not safe, many organizations—including nonprofits, academic clubs, and public libraries—moved their programming to online platforms. Despite the learning curves, the results were instructive and remarkable.

Reading Is Fundamental (RIF) Reacts

For nearly six decades, RIF has been working in communities, interfacing with educators and students, delivering free books for children to build their home libraries. Since 1966, RIF has been able to work hand in hand with communities to bring joy and excitement to children’s faces as they choose books to take home and keep. When most schools shuttered their doors for the school year and after it became clear that in-person events were no longer safe, RIF had to cancel book distributions, the cornerstone of their flagship program, Books for Ownership, that allows kids to browse a wide selection of books and take several home for free. Knowing that it was critical for kids to have access to books, the staff at RIF had to figure out a safe way to deliver books with social distancing guidelines in place.

Working with their partners, RIF devised plans to deliver books as a part of homework pickup programs and meal distributions. Instead of school librarians displaying books on tables for kids to select, heroic volunteers prepared and packaged books in bags that could be safely handed over to families as they waited in their cars.

Whereas students had typically enjoyed celebratory events with read-alouds to make their book choices, activities were pivoted to virtual events. While book browsing and choice had to be sacrificed, RIF concurrently highlighted the availability of their digital library, Skybrary, through free trials and continued to offer free reading resources on its book resource website, RIF.org/Literacy-Central.

RIF also conducted a national survey to direct its response and strategy for the ongoing children’s literacy challenges of the pandemic and created content and programming to address the learning losses of the 2020–2021 school year. Nearly 1,000 respondents including teachers, parents, and caregivers took the survey, which found that 96% of respondents were worried about both the decline in children’s reading motivation and the need to provide reading resources and support to parents and caregivers to encourage reading at home. Economic discrepancies were also highlighted: students lost precious access to books through school and the library, and many were isolated without home libraries.

One teacher said, “I feel like many of my students do not have access to books or the tools to enable them to read at home. I’m worried that I am losing my students who loved borrowing materials from our school library and do not have that ability and now they are losing interest.”

The survey findings were clear: there is a critical need to reinspire and re-engage children while providing tools to parents and caregivers so they can support reading. To specifically address this need, in the fall of 2021, RIF will launch Rally to Read 100, an engaging reading initiative that includes a pledge to read 100 books for classrooms across the country by Read Across America Day in March 2022 and a giveaway of 10,000 books to 100 schools.

Rally to Read will bring students and teachers together for six months of reading fun. With free resources available to everyone, teachers and their students will be able to attend monthly virtual read-alouds with notable authors and illustrators, access free book- and theme-related activities, and celebrate on Read Across America Day with a virtual culminating event.

Access to books in print is important, too (especially since many kids are digitally exhausted), so Rally to Read is an initiative that complements rather than replaces RIF’s Books for Ownership book distributions, which they are looking forward to reinstating as students return to classrooms this fall.

National Literacy Organizations Pivot

Ensuring continuity of reading and learning at a time when it is unsafe to gather has been a significant challenge for every literacy organization over the past 18 months. Everyone has had to shift, whether the shift was for the staff and volunteers, the readers, or both.

With most schools going virtual, shifting to virtual delivery for supplemental programs presented its own hurdles. How could libraries deliver something online that would match the energy of a group of kids in a circle on a bright carpet in their local library? How could a Saturday reading program, staffed entirely by volunteers, be compelling enough online to inspire kids to sign on over the weekend?

Libraries Adapt, Online

Just like niche reading programs, library systems across the country, both large and small, scrambled to offer story times and other programming for children online. Librarians gamely offered up virtual activities from their basements, dining rooms, and living rooms, which they’d transformed into library nooks with bookcases, tables, and music stands. One librarian in Virginia took young readers on a tour of her garden; another, in Maryland, introduced her dog, who always ran into the frame for the song “Open Them, Shut Them.”

From the very start of the pandemic, the Public Library Association was working to take a critical look at their services and to innovate ways to pivot. According to their survey spanning March 24–April 1, 2020, 98% of libraries had closed their buildings and 61% were adding virtual programming.2 In Montgomery County, Maryland, the library offered story times and other activities for children every day, including weekends, and sometimes multiple times a day. Participants could choose to turn their cameras on or leave them off, but children were greeted by name and unmuted for group goodbyes. It was profoundly generous and critically important for keeping kids engaged with books and libraries.

Students and Volunteers Stay Connected

Reading All-Stars (RAS), a literacy program from the nonprofit creative writing organization 826DC, was designed to support one-on-one meetings between volunteer mentors and elementary school students. On Saturday mornings, up until March 2020, volunteers met their reading buddies in the cafeteria and then split off to read in pairs for two hours.

Both the students and the volunteers were dedicated and engaged, showing up in the rain and snow, and on beautiful spring days too, to read and write together. When the pandemic hit, no one knew how the experience could translate online. “The program is focused on creating a positive space for learning and reading, and we wanted to figure out a way to maintain that connection with students and families during this really stressful time,” Kalli Krumpos, RAS coordinator, said. The all-volunteer coordinators started getting the word out to students and volunteers that they would use a virtual platform to continue to meet, breaking out into private sessions for paired reading. A few new rules had to be put in place—two volunteers per student, shorter sessions—but every Saturday, week after week, volunteers signed on and kids joined minutes later. There were some bumps—a lost connection here, a distracting sibling in the background there—but, according to Ms. Krumpos, “It was a bright spot in a dark time and shows what real community can do. We now know that, when we need it, this model works.”

More Ready Than Ever

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced a crisis on many fronts. It has been scary, heartbreaking, and challenging. But it has also allowed for meaningful preparation for educators and policymakers to help them meet the needs of all students at all times. This pandemic has shown us that, ready or not, we can and must pivot to meet all children’s needs. While in-person interactions are deeply important for children, we now know that we can make a difference for millions of students when we pivot and adjust, even when maintaining engagement suddenly requires passing reading materials through a car window or sharing a lively read-aloud online.

Whether providing a literacy event presented entirely online, a virtual space for students to meet volunteer reading buddies, or story times direct from a librarian’s house, organizations got creative during the pandemic and will surely take the best parts of their new programming into the future, pandemic or not.

Help kids enjoy reading! Share a story time | Gift a book | Donate to an organization

Links

1. www.nwea.org/content/uploads/2021/07/Learning-during-COVID-19-Reading-and-math-achievement-in-the-2020-2021-school-year.research-brief-1.pdf

2. https://www.ala.org/pla/sites/ala.org.pla/files/content/advocacy/covid-19/PLA-Libraries-Respond-Survey_Aggregate-Results_FINAL2.pdf

Alicia Levi currently serves as president and CEO of Reading Is Fundamental. Prior, Alicia served as vice president of education for the Public Broadcasting Service (PBS). Before joining PBS, Alicia served as vice president of educational publishing at Discovery Education and, earlier, managed the University of Maryland College Park’s Educational Access Channel.

Jeanette Edelstein is an educator dedicated to making learning fun for students of all ages. She has taught in middle and high schools and currently focuses on K–12 curriculum and instruction. She holds a master’s degree in education from the University of Colorado.