|

Supporting young children’s language and literacy development has long been considered a practice that yields strong readers and writers later in life. The results of the National Early Literacy Panel’s (NELP) six years of scientific research synthesis supports the practice and its role in language development among children ages zero to five.

Supporting young children’s language and literacy development has long been considered a practice that yields strong readers and writers later in life. The results of the National Early Literacy Panel’s (NELP) six years of scientific research synthesis supports the practice and its role in language development among children ages zero to five.

The NELP was brought together in 2002 to compile research that would contribute to educational policy and practice decisions that impact early literacy development. It was also charged with determining how teachers and families could support young children’s language and literacy development. Outcomes found in the panel’s report (2008) would be used in the creation of literacy-specific materials for parents, teachers, and staff development for early childhood educators and family-literacy practitioners. Through its work, the NELP uncovered a set of abilities such as alphabet knowledge, oral language, or phonological awareness present in the preschool years that provides the basis for later reading success.

It also found that measures of complex and discourse- level skills are particularly strong predictors of reading success – a finding that is consistent with the fact that language is a complex, multidimensional system that supports decoding and comprehension as children learn to read. In our book Early Childhood Literacy: The National Early Literacy Panel and Beyond, we explore the NELP report, as well as newer research findings and the effectiveness of specific approaches to teaching early oral language development to establish a solid foundation for later reading comprehension.

Below we expand on concepts to help educators understand how oral language relates to reading comprehension, word reading, and language development; where Common Core State Standards factor into the equation; and what teachers can do to foster literacy development.

Laying Down the Building Blocks

Through its research, the NELP discovered that the more complex aspects of oral language, including syntax or grammar, complex measures of vocabulary (such as those in which children actually define or explain word meanings), and listening comprehension were clearly related to later reading comprehension, but that simpler measures of oral language (e.g., the widely used Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test) had very limited associations with reading comprehension.

Put simply, readers must translate print to language and then, much as in listening, they must interpret the meaning of that language. Numerous studies support this approach by showing that word reading and language comprehension are relatively independent skills, but that each contributes significantly to reading comprehension. Simple measures of vocabulary in which children simply point to the picture of a word or name a picture are not strongly connected with later reading comprehension. Nevertheless, many studies have shown that vocabulary plays an important role in fostering reading development in the years before and during formal reading instruction.

The role of vocabulary is likely two-fold. The words, and the concepts that they represent, are obviously of functional importance in comprehension, and vocabulary might also support decoding or the translation of text into language. The NELP established phonological awareness as a key contributor to children’s ability to learn to read. Of course, phonological representations are part of the linguistic system and the ability to gain access to these representations may in part be a by-product of early vocabulary development (Metsala & Walley, 1998). Reading comprehension depends on language abilities that have been developing since birth. Basic vocabulary and grammar are clearly essential to comprehension because each enables understanding of words and their interrelationships in and across individual sentences in a text (Kintsch & Kintsch, 2005).

However, children who comprehend well go beyond word and sentence comprehension to construct a representation of the situation or state of affairs described by the text. In some theories, this is referred to as a “mental model” (Kintsch & Kintsch, 2005) and it involves organizing a text’s multiple ideas into an integrated whole, using both information from the text and the reader’s own world knowledge. To do this, successful comprehenders draw upon a set of higherlevel cognitive and linguistic skills, including inferencing, monitoring comprehension, and using text structure knowledge. Take the following story for example: “Johnny carried a jug of water. He tripped on a step. Mom grabbed the mop.”

The literal representation of the individual words and sentences does not enable the reader to integrate their meanings and construct a mental model. Successful comprehenders understand narrative structure and couple it with their knowledge to infer that Johnny spilled the water. They then understand why Mom grabbed a mop.

They also monitor their comprehension of stories-either written or spoken-and realize the need to make an inference (that Johnny spilled the water) to make sense of Mom’s response. High-level language skills used to create mental models of text are not exclusive to reading. In fact, children begin developing these language skills well before formal reading instruction in a range of language comprehension situations. For example, young children rely on knowledge of narrative structure to do things like follow a set of instructions, share their daily activities around the dinner table, or understand spoken stories, cartoons, and movies.

Assessing Early-Stage Development

The skills needed for reading comprehension come into play as students progress. In the early grades, for example, reading comprehension depends heavily on emerging word-reading skills. As children accomplish the ability to automatically and fluently read printed words, language comprehension begins to contribute more to individual differences in reading comprehension. Most children who score poorly on reading comprehension tests have difficulty decoding words and understanding language.

Those with poor word-reading abilities (i.e., poor decoders) lag behind their typically developing peers on reading comprehension measures in the early grades, even if they have good language development. However, those with poor language comprehension, in spite of relatively proficient word-reading ability, usually do not lag behind their typically developing peers on reading comprehension tests until they have had one or two years of reading instruction (Catts et al., 2005). It’s important to point out that what appears to be a decline in reading comprehension for poor comprehenders is not the result of declining language skills. In fact, these students’ language skills were already poor compared with their typically developing peers at the onset of schooling.

A recent report found that poor comprehenders in fifth grade (i.e., those with poor reading comprehension despite good word-reading abilities) evidenced weak language skills as early as 15 months of age (Justice, Mashburn, & Petscher, in press) compared with their agematched peers who went on to become good comprehenders and poor decoders, and NELP found that early language skills were predictive of later reading comprehension development, but much less so with early decoding skills.

Subsequently, many students who are labeled as “clinically language impaired” prior to, or just beginning, formal education in preschool or kindergarten, do not necessarily have problems learning to read initially (Catts, Fey, Tomblin, & Zhang) Their later “decline” in reading comprehension is thought to be related to the changing nature of reading comprehension assessments: the texts used to assess reading comprehension in the early grades require less complex mental models and very limited language processing, allowing those with weak language skills to answer basic comprehension questions as accurately as their typically developing peers.

In the later grades, however, reading comprehension assessments contain more difficult passages that require more complex mental models. Poor comprehenders lack the language skills needed to construct these complex mental models and begin to score more poorly on reading comprehension assessments when compared to their typically developing peers. Poor decoders with good language comprehension abilities may be able to compensate to some degree for their weak wordreading abilities in the later grades. That’s because even though they might struggle to decode all of the words, their language skills allow them to bootstrap their way to the text’s meaning, using their good language skills and rich knowledge of the world to help construct sufficient mental models to correctly answer comprehension questions (Stanovich, 1980).

Helping Children “Crack the Code”

According to our book, a key challenge facing the beginning reader is the ability to “crack the code” or, learning how written language maps onto spoken language. This is because better decoders devote greater cognitive resources to the processes involved in comprehending text. Children’s oral language skills serve as the foundation for both aspects of reading ability-word reading and language comprehension.

Because few preschool children can yet read words, we must look at precursor skills that develop into word recognition or decoding ability. Knowledge of the alphabet and phonological awareness are both strong predictors of later decoding and comprehension, and it is evident that teaching these in combination has a consistently positive impact on improving students’ later decoding and reading comprehension abilities. Rapid naming, knowledge about print conventions and concepts, the ability to write letters or names, and oral language skills were also good predictors, but teaching these has not consistently led to gains in reading success.

How the Common Core Factors into Literacy Development

With 46 states now working to implement the Common Core State Standards which include grade-specific K-12 standards in reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language, educators may be required to adjust their lessons to align with the standards and assessments used to determine student progress. But what if the road to success with those standards begins when the student was an infant, toddler, or preschooler?

This question was clearly answered through the NELP’s extensive research, which emphasized the importance of print knowledge, phonological processing abilities and oral language skills as important predictors of later literacy skills, and with evidence that teaching these early on can have long-term benefits. Additionally, assessment of these early literacy skills is important for identifying children who are likely to need more intensive instruction to achieve success with literacy. By identifying and working with students across all literacy levels at a very early age, today’s educators can take a proactive role in ensuring that students meet or exceed standards across the board.

Making a Difference: The Teacher’s Role in Literacy Development

Interventions focused on fostering language aren’t easy to develop or implement. The interconnected and complex nature of language comes with a long developmental history and draws on a broad range of linguistic and cognitive capacities. Furthermore, interventions occur within a social context where motivational, behavioral, and social factors can impact the learning climate. Children’s attention to language input and their willingness to respond to it are affected by a host of factors, including their interest in the topic of the conversation, their relationship to the speaker, the number and identities of other conversational participants, and the setting.

Even more vexing is the fact that teachers — the most important source of language input in preschool classrooms — have a history of using language in ways that may not be consistent with the interactions found by research to be conducive to language learning. Teacher’s interactions that best encourage language learning include having conversations that stay on a single topic, providing children opportunities to talk, encouraging analytical thinking, and giving information about the meanings of words. For teachers, key considerations for instruction include the fidelity of the implementation (an extremely important aspect); teaching children letter names and sounds by performing phonological awareness tasks; and understanding that there is no link between curricula with a systematic and explicit focus (i.e. teacher-directed) and negative social-emotional outcomes for children.

Response to intervention in preschool holds promise for successful early language development but several key issues must be considered. For one, preschools often serve disproportionate numbers of children who need Tier 2 or Tier 3 services, which causes staffing concerns. Also, more research is needed on the effect of interventions for children from low-income families, children with disabilities, English language learners, and children from underrepresented ethnic groups. The NELP report, along with other studies of children’s early language development, suggests that early oral language has a growing contribution to later reading comprehension — a contribution that is separate from the important role played by the alphabetic code.

As such, improving young children’s oral language development should be a central goal during the preschool and kindergarten years. In the end, making strides in this area of a child’s educational development can begin with a very simple exercise shared book reading. Although various approaches have been found to improve young children’s language, the approach of shared book reading has gained the greatest research support thus far, particularly when such reading is carried out dialogically, that is, with much language interaction between the reader and the child.

Combining shared book reading along with other language activities with explicit decoding instruction in the context of a supportive and responsive classroom, can make the difference between a child whose literacy development is at or above standards or one who struggles with reading, writing, and literacy throughout his or her K-12 education.

References

Catts, H.W., Fey, M.E., Tomblin, B.J., & Zhang, X. (2002). “A longitudinal investigation of reading outcomes in children with language impairments.” Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 45, 1142-1157. Catts, H.W., Hogan, T.P., & Adlof, S.M. (2005). “Developmental changes in reading and reading disabilities.” In H.W. Catts & A.G. Kamhi (Eds.), The connections between language and reading disabilities (pp. 25-40). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Justice, L.M., Mashburn, A., & Petscher, Y. (in press). “Very early language skills of fifth-grade poor comprehenders.” Journal of Research in Reading. Kintsch, W., & Kintsch, E. (2005). “Comprehension.” In S.G. Paris & S.A. Stahl (Eds.), Current issues in reading comprehension and assessment (pp. 71- 92). New York, Routledge. Metsala, J. L., & Walley, A. C. (1998). “Spoken vocabulary growth and the segmental restructuring of lexical representations: Precursors to phonemic awareness and early reading ability.” In J. L. Metsala & L. C. Ehri (Eds.), Word recognition in beginning literacy (pp. 89-120). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. Perfetti, C.A. (1985). Reading ability. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. Stanovich, K.E. (1980). “Toward an interactive- compensatory model of individual differences in the development of reading fluency.” Reading Research Quarterly, 16, 32-71.

Timothy Shanahan, Ph.D., and Christopher J. Lonigan, Ph.D., are the editors of Early Childhood Literacy: The National Early Literacy Panel and Beyond, available from Brookes Publishing Co. They are two of the nation’s top childhood literacy experts and served on the National Early Literacy Panel (NELP).

Supporting young children’s language and literacy development has long been considered a practice that yields strong readers and writers later in life. The results of the National Early Literacy Panel’s (NELP) six years of scientific research synthesis supports the practice and its role in language development among children ages zero to five.

Supporting young children’s language and literacy development has long been considered a practice that yields strong readers and writers later in life. The results of the National Early Literacy Panel’s (NELP) six years of scientific research synthesis supports the practice and its role in language development among children ages zero to five.

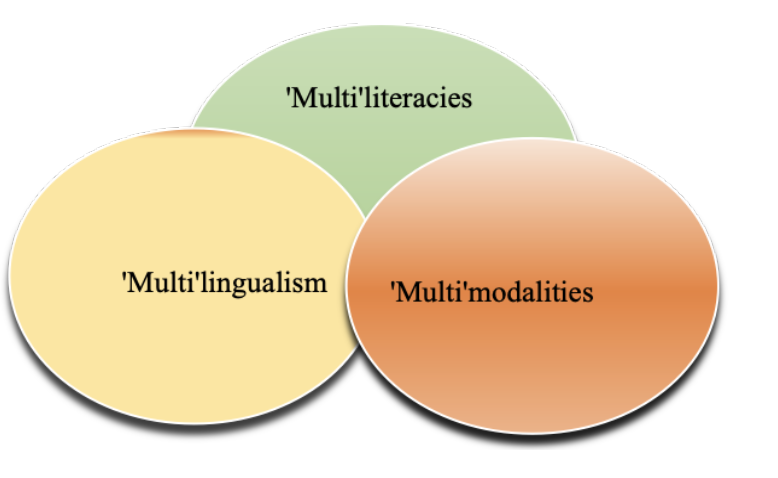

International Education Week (IEW) is an opportunity to celebrate the benefits of international education and exchange worldwide. This joint initiative of the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of State highlights the value of global and cultural competencies and promotes programs that help U.S. students and teachers develop global skills for success in the 21st century. The Department of Education’s I

International Education Week (IEW) is an opportunity to celebrate the benefits of international education and exchange worldwide. This joint initiative of the U.S. Department of Education and the U.S. Department of State highlights the value of global and cultural competencies and promotes programs that help U.S. students and teachers develop global skills for success in the 21st century. The Department of Education’s I