Introduction

In a rural part of northwest Alabama sits Russellville City, a community that has experienced tremendous demographic changes in recent years. These changes are reflected in the local school district, Russellville City School District (RCSD), which has seen the number of students identified as English learners (ELs) increase from 16 percent of enrollment in 2014–15 to nearly 30 percent in less than a decade.[1] In response to local pressure, the state recently boosted EL funding—between 2018 and 2021 allocation increased from $2.9 million to $16 million—which amounts to $300 per EL for RCSD on top of basic per-pupil funding.[2] District leaders have used these funds in conjunction with other state, local, and federal revenue to hire EL paraeducators and teachers, and to help Spanish-speaking staff members become certified teachers. Still, local education leaders say more money is needed.

School districts across the country, like RCSD, are grappling with the challenge of determining how much funding is needed to provide ELs with rigorous and equitable learning opportunities. New America convened a group of education finance and EL education policy experts in July 2022 in order to discuss equity gaps in how EL education is funded (please scroll down for the full list of attendees). Attendees were divided into two groups, where they discussed four guiding questions:

- What, if anything, are the current flaws in how EL education is funded?

- Which, if any, states/districts currently provide adequate funding for EL education? What do we know about the funding structures in places that have good outcomes for ELs?

- What would it take to determine the true cost of educating ELs across various contexts?

- What are the benchmarks that can be used to measure the cost of educating ELs uniformly across school/district/state?

This brief will summarize what we learned from this roundtable. It will give a short overview of EL funding context in the U.S., followed by five key takeaways that emerged from the discussion central to making progress towards more equitable funding systems for ELs.

Background

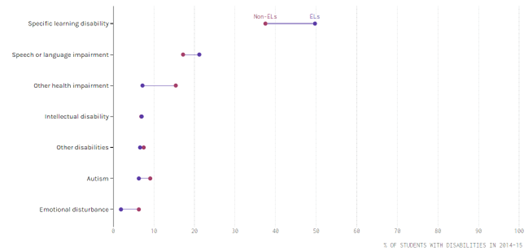

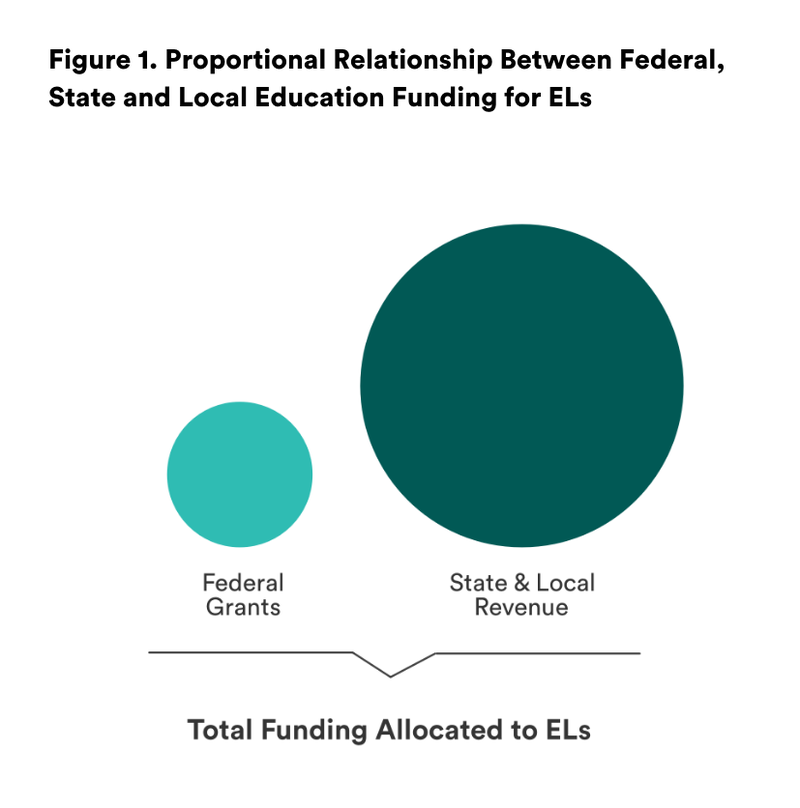

The bulk of K–12 education funding comes from state and local revenue, which means that states and districts are covering the costs of providing core EL services and programming.[3] In addition to the base per-pupil funding, most states provide increased funding for ELs by using student-weighted formulas, categorical funding, reimbursement agreements, and sometimes a combination of these methods.[4] The federal government provides supplemental funding for ELs in K–12 through one designated revenue stream, but ELs qualify to be served by other federal programs as well (see Federal Funding for English Learners).[5]

Federal Funding for English Learners

Funding for ELs is provided through the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965, most recently reauthorized in 2015 through the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), and by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Refugee Support Services Formula Allocation.[6]

- Title I, Part A: Improving Basic Programs Operated by Local Educational Agencies

Provides grants to local educational agencies (LEAs) for improving the academic achievement of economically disadvantaged students. - Title I, Part C: Education of Migratory Children[7]

Provides grants to state educational agencies to assist in supporting high-quality and comprehensive educational programs and services during the school year and, as applicable, during summer or intersession periods, that address the educational needs of migratory children. - Title II, Part A: Supporting Effective Instruction

Provides grants to state educational agencies, which then sub-grant funds to LEAs to improve teacher and principal quality through induction programs, professional development and growth, equitable access to quality educators, and recruitment for hard-to-find educator positions. - Title III, Part A: English Language Acquisition, Enhancement, and Academic Achievement

Provides grants to state and local educational agencies to help implement programs that help ensure ELs, including immigrant children and youth, attain English proficiency and develop high levels of academic achievement in English.[8]This is the only grant program that is specifically geared towards supporting ELs and recent immigrant students in the classroom. - Refugee School Impact Grants

Provides grants to state and state-alternative programs to support school districts impacted by school-aged refugees and Office of Refugee Resettlement-eligible populations.

Congress appropriates money to each of these discretionary grants every year, and how much each state receives is determined using a specified formula. For Title III, for example, each state receives funding based on how many ELs and recent immigrant students are enrolled.[9] States are responsible for distributing the money to local school districts who use the funds for district-wide resources or release the funds to individual schools. Since ELs tend to be overrepresented in low-income schools[10] and the number of teachers prepared to support these students in bilingual and English as a second language (ESL) classrooms is limited, funds provided under Title I, Part A and Title II, Part A can be used. Although not all refugee and migratory children are ELs, many are, so Title I, Part C and Refugee School Impact Grants can be used to support those students.

Education advocates have been pushing for more federal funding for ELs for years, calling attention to the fact that funds have not kept up with the pace of growth among the EL population.[11] In the past 20 years, the EL population grew by 35 percent, yet funding for EL students through Title III—the federal funding stream designated for ELs—decreased by 24 percent when adjusted for inflation.[12]

Much of the advocacy by EL-focused national organizations has aimed to increase Title III funding, but the decentralized nature of education in the U.S. means that state and local revenues play a much larger role than federal funds. In fact, combined state and local revenue made up 80 percent or more of every state’s total K-12 education funding in 2017-18. Districts received, on average, just 8 percent of funding from the federal government.[13]

Previous research has found that state funding structures do not direct more resources to districts with the highest needs (see What Do We Mean by Equity and Adequacy? for what we mean by equity and adequacy). For example, a December 2022 report from the Education Trust found that districts with the most ELs receive approximately 14 percent less state and local revenue than districts with low EL enrollment. This means that although nearly every state, plus the District of Columbia, allocates additional funds for EL education on top of baseline per-pupil allocations, schools and districts where ELs are concentrated are at a disadvantage. Education finance research commonly recommends incorporating differentiated funding levels for ELs to account for their varying needs.[14] However, information is scarce about how many additional resources are required to adequately and equitably meet their needs.

What Do We Mean by Equity and Adequacy?

This brief will apply the concepts of equity and adequacy as defined in “How States Fund Education,” where Ajay Srikanth, Michael Atzbi, Bruce D. Baker, and Mark Weber base their education finance work on the following terms:

- Vertical equity calls for distributing resources differently according to the need, which when applied to education finance means that students with greater needs should receive more resources and greater levels of funding.

- Adequacy is the amount and level of resources sufficient to assist students with different educational needs in obtaining a set of defined educational outcomes across different settings. To determine adequacy, three major components need to be defined:

1. What are the desired outcomes?

2. Which groups of students have greater needs? And,

3. What are the resources required to achieve these outcomes and how do they vary across contexts?

Source: “How States Fund Education,” in The Oxford Handbook of U.S. Education Law, ed. Kristine L. Bowman (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2018), online edition, page 2 in PDF, https://doi.org/10.1093/OXFORDHB/9780190697402.013.10.

A 2012 review of 70 empirical cost studies conducted by Oscar Jimenez-Castellanos and Amelia M. Topper found that ELs have mostly been excluded from large-scale cost studies, making it difficult to understand the true cost of providing them with an adequate education.[15] However, smaller-scale studies have helped establish some parameters around how to approach questions of EL funding adequacy and equity. First, EL funding varies at all levels of distribution, from federal, state, district, all the way to individual schools.[16] Second, funding adequacy is context-specific.[17] Third, what is considered “enough” is closely tied to the programming and services provided, as well as the goals of instruction.[18] Finally, traditional measures of success/student outcomes used in determining whether adequate funding is provided are not always appropriate measures of gauging EL learning and growth.[19]

Roundtable Takeaways

1. Funding systems lack nuance and are loosely linked to EL-specific outcomes.

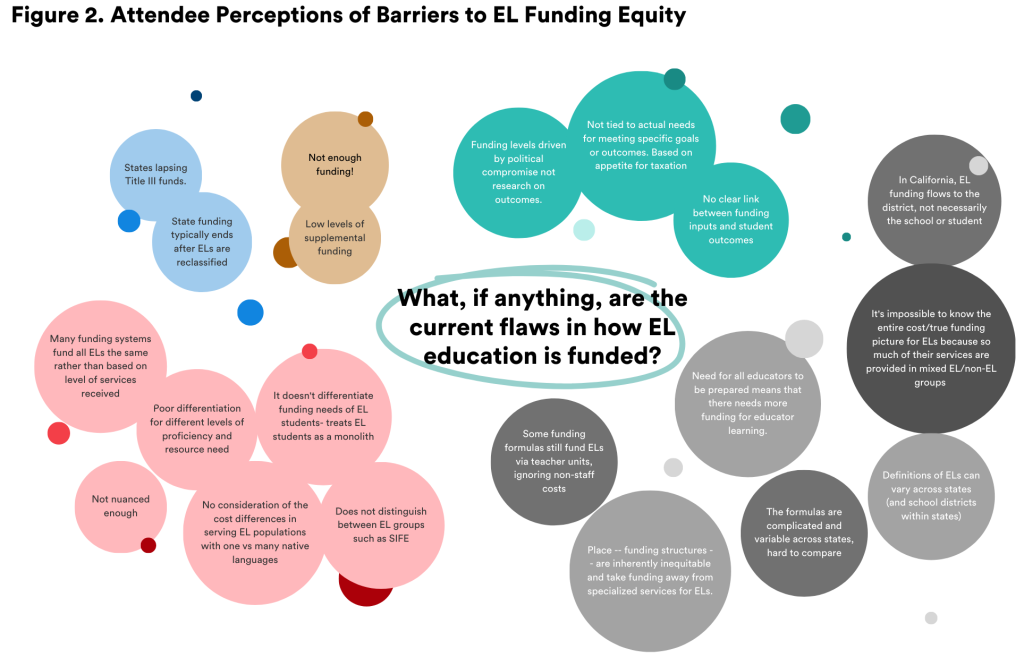

Meeting attendees were asked to reflect on EL education funding. They posted their thoughts on an interactive online tool and identified 20 problems which we organized and color-coded (see Figure 2).

The top issue, noted in pink, was that funding systems are not nuanced enough to account for the different needs of EL students. Participants said that ELs’ educational needs can vary depending on English proficiency level, grade, how recently students arrived in the country, and if students have experienced interrupted schooling. Costs to a district can depend on whether there is one predominant language among the EL population, or if many home languages are spoken. The EL population has become increasingly diverse in the U.S. [20] and funding mechanisms have not kept up with these changes.

Another top issue, noted in dark green, was that funding levels are rarely linked to actual EL education needs, goals, and/or outcomes. Funding levels and decisions are often driven by political compromise and a state’s appetite for taxation rather than research and evidence on the services that result in the best outcomes for students.

Attendees also called attention to the fact that both federal and state funding for ELs typically ends after a student is reclassified as English proficient, which is noted in blue. The two beige notes reference insufficient funding as a key issue. The notes in grey do not have a particular theme.

2. Funding adequacy for ELs is not well conceptualized or understood.

Participants were not able to identify a state or district that provides adequate funding for ELs, mainly because there are still many challenges to how adequacy is conceptualized and understood in relation to EL education. For example, many adequacy studies and funding conversations are focused on specific outcomes that different funding mechanisms produce—outcomes that are often narrowly defined by standardized academic assessments.

However, participants said that using standardized test scores as indicators of whether ELs are being provided with adequate services (and funding) is problematic and largely unfair. Standardized English language arts (ELA) and math assessments, participants noted, have long-standing limitations in their ability to accurately and validly represent what linguistically diverse students are capable of academically.[21] These limitations begin with the monolingual approach to assessment in the U.S.[22] For example, assessments may not be normed based on a representative sample of ELs with more non-ELs represented in the sample. This means test norms tend to be skewed toward non-EL performance.[23] Furthermore, every test, whether it be science or social studies, inadvertently tests the English skills of these students.[24]

“To address adequacy, you need to address the funding side, [as well as] the outcomes [side]. On the outcomes side for ELs this includes English Proficiency, test scores in math and ELA, academic content knowledge, native language development, and long-term outcomes such as graduation rates, college attendance/persistence, and earnings.”

—Ajay Srikanth

Participants discussed the implications of relying on this data, particularly if linguistic accommodations are not being provided, and the need to redefine what “good outcomes” are for these students. Attendees also explored alternative measures that could be used to better define what it means for a school to provide “good outcomes” for English learners. These included whether ELs are meeting their annual growth targets; whether ELs are reaching proficiency within their personalized maximum timeline to proficiency; and the number and proportion of students considered long-term English learners (LTELs).[25]

3. More work is needed to account for EL-specific variables that positively and negatively impact their educational outcomes.

As participants discussed what it would take to determine the “true” or “adequate” cost of educating ELs, it quickly became evident how difficult it is to disentangle “EL costs” from broader services and expenditures, since the sum of students’ education extends beyond the language services they are provided.

Participants called attention to the number of variables in EL education that make it difficult, if not impossible, to come up with a number that would represent equitable and adequate funding for all ELs. One of these variables is the instructional model used (i.e., dual language/bilingual, push-in and pull-out ESL, and co-teaching) and the costs associated with different approaches. As previous research has pointed out, as pedagogy changes, so do the resources needed to implement new approaches.[26] Other variables discussed include geographic location, whether there is a large or small EL presence in a school/district, and the level of linguistic diversity among the EL population.

“It’s incredibly complicated, given all of the different contexts, the ways that students are provided services, the quality of the services, the policies in place at the state level. Everything just folds into making it a very hard number to actually pin down.”

—Julie Sugarman

This conversation highlighted the fact that we need to better understand and identify the additional services (inputs) these students need to achieve desirable education outcomes. That is, what do ELs need that non-ELs do not, and how much do these things cost?

Since the rights of ELs are enumerated in federal policy and various court cases,[27] a good starting point is to look at language-related services and programs. According to ESSA, ELs should be meeting their annual growth targets and reaching the state’s English language proficiency (ELP) threshold in a certain amount of time, so what services should schools be providing to help make that happen? Participants remarked that states and districts have the capability to measure and track specific inputs, but they need clarity on which ones, or combinations, lead to better outcomes for ELs, both linguistic and academic.

A non-exhaustive list of ideal language-related services discussed during the meeting includes:

- Bilingual school counselors, social workers, and school psychologists

- Bilingual family liaisons

- Small teacher to student ratios/small class sizes

- Extra tutoring

- Bilingual teachers and paraeducators

- Professional development and supplemental materials for mainstream/content teachers

- Translations and interpreters

- Welcome centers to support screening and enrollment

“States, and probably districts, are pretty good at measuring specific inputs. So if we could agree on what kind of combination of those inputs we’re aiming for in getting to an outcome, that might be a good first step.”

—Laura Hill

Participants also emphasized the need to ensure that EL students have access to rigorous core curriculum, AP courses, and gifted and talented programs, and that they graduate from high school at a rate similar to that of their non-EL peers. More broadly, participants discussed what “successful schooling” should look like for these students, which includes an asset-based orientation toward bilingualism and biculturalism.

During this conversation, a tension was identified between the motivation to quickly reclassify ELs and the desire to think about what long-term success looks like for these students. This tension is not just a set of conflicting academic aims but a misalignment of financial incentives. Due to the legal requirements that come with EL classification, it may be less costly for a state to have fewer students classified that way. And in some places, EL supplemental funding to help meet those requirements may only be available for a limited number of years. In Iowa and Colorado, for example, ELs are eligible for supplemental state funding for no more than five years. In North Dakota, students performing at a Level 3, or intermediate English proficiency, receive supplemental funding for up to three years.[28]

Several of the group members coalesced around this idea about the misalignment between the short-term goal of testing out of EL status and long-term goal of academic proficiency, and the even greater goal of developing bilingual and bicultural students. They felt this disconnect should be considered in any conversation seeking to define what it means to produce “good outcomes” for ELs. This long-term view means that both currently identified ELs and former ELs must be kept in mind when it comes to ensuring adequate funding.

Lastly, participants discussed the importance of knowing whether language development programs, such as dual language immersion (DLI), or sheltered instruction, are helping students grow from one ELP level[29] to the next, and determining the cause if/when a student stops progressing. Participants felt that focusing on growth on the ELP assessment over time makes more sense than looking at other outcomes that are not linked to markers of EL-specific success.

4. Methods used in school finance scholarship could be better-tailored to the diversity of EL students and their educational contexts.

The group discussed how quantitative methods, such as cost function analysis (CFA), are commonly used in funding adequacy studies. According to a 2000 report from the Center for Policy Research in Education, “cost function provides an estimate of the minimum amount of money necessary to achieve various educational performance goals, given the characteristics of a school district and its student body, and the prices it must pay for inputs used to provide education.”[30] Participants said that the variables used in CFA studies often do not capture fine-grain distinctions between EL subgroups (i.e., LTELs, recently arrived students, etc.) or geographic differences between school districts (such as those that are rural/remote and/or have sparse EL populations), which are important when determining funding adequacy for these students.

“Cost functions are a rigorous approach to calculating the cost of an adequate education. They do, however, face certain limitations with respect to data quality and availability. The next step to improving cost functions would be to collect and use higher quality data that distinguishes ELs by need (English proficiency, years of schooling, SIFE) and to use higher quality spending data.”

—Ajay Srikanth

Participants cautioned that in CFA, the granularity and quality of data are the most important considerations in ensuring accurate estimates. Although CFA may result in a higher numerical estimate than a purely qualitative approach, qualitative data can provide more specialized information about context that can help show the true cost of educating these students in specific communities. Participants discussed how conducting CFA in conjunction with qualitative approaches like a professional judgment panel[31] can provide more reasonable estimates.

Participants brainstormed other ways that could fill the EL adequacy gap in school finance scholarship. Ideas include looking at places that are getting “good outcomes” for ELs, identifying the practices and services being implemented that are known to be effective for ELs, and modeling out how much those services would cost in different contexts. In other words, a budget analysis could show the expenditures necessary to provide best practices for supporting holistic EL development. Another idea was studying the costs of different language instruction models. Research examining this issue is scarce,[32] which makes it difficult to understand whether implementing a DLI program is more costly than implementing an English Language Development program, and how those costs bear out in terms of student outcomes.

5. ELs should be integrated into every component of state and district funding structures.

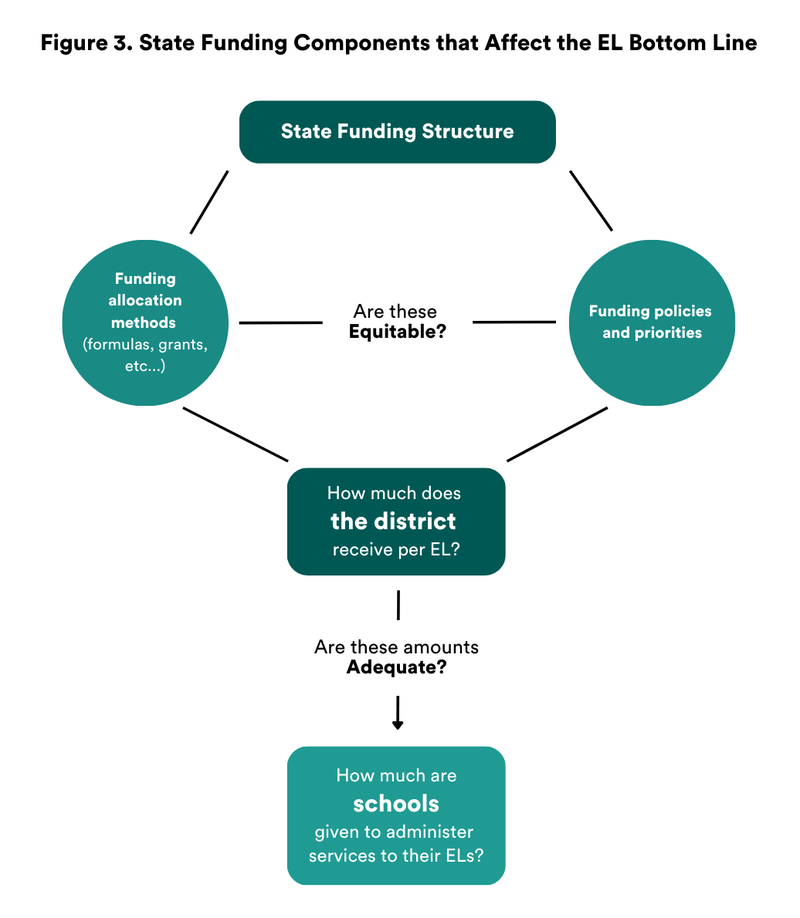

Every part of a state’s education funding structure can impact whether funding levels are equitable and adequate. How much funding EL students receive at the district and school level depends on both the method used to allocate funds and the policies and priorities established by the state (see Figure 3). A lot of attention in education funding is placed on the formulas and methodologies used to distribute funds. However, it became clear during our discussion that a state can have the “best” formula that weighs ELs high and still provide inadequate resources due to other conflicting and inequitable policies.

For example, Georgia provides one of the highest weights for ELs, at 2.588 meaning that per-pupil funding is two and half times that of a non-EL student.[33] However, it also provides one of the lowest base funding levels in the country (just $2,897 per pupil in FY 2023[34]) which limits how much additional funding the weight can actually generate.[35] This is because the weight is a multiplier, and 2.588 times this very low base number might produce less money than a low weight that is applied to a much higher base. For example, Connecticut’s 1.25 EL weight is applied to a much more generous $11,525 base, which results in more funding per EL—$14,406 total funding per EL to Georgia’s $7,498.[36]

Participants identified and discussed various policies that undercut EL funding equity and preclude schools from providing adequate services. For example, state and federal EL funding is only provided for students currently identified as an EL. However, participants discussed the need to fund support for students after they are reclassified, at least for a limited time. Federal law requires states to monitor the academic progress of recently exited ELs for a minimum of two years,[37] but school districts do not receive additional funds to support those efforts. If funding was provided, even for a limited number of years, schools may be able to continue to support their linguistic development. This could help reduce the probability that a student will backslide after reclassification while ensuring they have access to the full curriculum which is not necessarily available while students are classified as ELs.

“I’m hesitating to say, ‘Oh, well, this state funding structure will produce good outcomes for ELs’ when there are so many intervening practice decisions between the decision of the state to structure funding a certain way and the decision of the teacher that affects the student experience and how the structure of the funding is going to impact those incentives and things like that.”

—Zahava Stadler

Participants remarked that nothing precludes a state from providing former ELs with funding and services, though federal law does limit Title III supplemental funds to currently identified ELs. New York was raised as an example of a state that has shown that it is possible to support former ELs by providing a step-down funding weight for these students in their first year after reclassification.

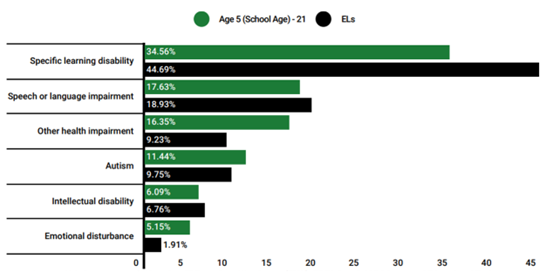

A significant amount of time was spent discussing how state funding structures do not account for students’ intersecting needs. ELs are more likely to experience homelessness, attend a Title I school (economically disadvantaged), or be a migratory student, compared to the overall student population.[38] In addition, roughly 15 percent of ELs are dual-identified for special education services.[39] However, many state funding structures treat students as one-dimensional beings and do not allow students to receive funding for all applicable categories.

It is important to note that not being proficient in English is not a disability, a distinction clearly made in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA).[40] However, there are commonalities in how we fund the educational needs of these two groups of students, which complicate the distinction between them in law and in practice.

Participants talked about the ability to “stack” weights on top of each other in places where additional funding is provided for students who may need additional support if they come from low-income backgrounds, have a disability, or are still learning English. California, for example, provides additional funding for students who fit into those three categories. However, per state policy, a student who is both low-income and an EL cannot receive funding for both categories.[41] Extra funding for “high-needs” students is determined using “unduplicated” counts of students, whereby a student who is low-income, EL, and in foster care is only counted once, and hence generates additional funding for only one of those categories.[42] California recently attempted to address this issue by allocating more funding to districts where unduplicated students make up 55 percent or more of its population.[43] These districts receive an extra 50 percent of the base grant for each high-need student beyond the 55 percent threshold. Here, it is not about the needs of the individual child, but the collection of high needs that generates more funding.

Participants also discussed how schools and districts in rural areas and/or with low EL density experience “diseconomies of scale,” which means that the cost of educating ELs increases because there are simply not enough ELs to make spending efficient, or services have to be spread out over a large geographic area. This funding variability can also pose a challenge if there are many different languages spoken by EL students, which can affect the nature of the program and staffing. Attendees remarked that regardless of how much teachers are prepared, funding limitations affect their ability to meet the needs of these students. On the other hand, places with higher EL enrollment generate more state and federal funding to provide bilingual specialists, family liaisons, and other supplementary services, in addition to the core language development program.

States such as Vermont, which has many rural districts, have moved to remedy this issue by ensuring that a baseline amount of money will be provided for basic support services. The state created a categorical grant to provide schools/districts with one to five ELs a $25,000 grant, and those with six to 25 ELs a $50,000 grant, enough for one full-time equivalent (FTE) employee.

Changes in enrollment can sometimes lead to significant reductions in funding for schools and districts. Some states have created temporary or longer-term “hold harmless” provisions.[44] Such clauses aim to ensure that no district falls below its historical funding levels, to help shield districts from changes that have budgetary ramifications, like declining enrollment, property value reductions, or even state allocation methods. Temporary hold-harmless policies are meant to give districts time to adjust to new budgetary realities.

Lastly, attendees briefly touched on the fact that ELs may be underfunded at the local level because of the methods used to determine each district and school’s per-pupil funding allocation. States determine local funding allocations using student enrollment on a single day or the attendance average over several dates; the average daily attendance over all or most of the year; or the average daily enrollment over all or most of the year.[45] Meeting attendees echoed previous research in urging states to assess their chosen methodology to ensure that ELs are not being undercounted and therefore underfunded.

For example, the rate of chronic absenteeism among ELs has been increasing in recent years,[46] which means attendance-based student counts would likely shortchange districts serving more ELs relative to enrollment-based student counts. And even when state formulas fully account for the number of students in need of EL services, districts are not necessarily required to pass on all the EL formula funding to the schools where those students are enrolled. As a result, some states have adopted policies requiring a specific amount be passed through. For example, state law in Maryland requires districts to pass through 75 percent of the per-pupil amount they receive for ELs enrolled in their jurisdiction to individual schools.[47]

Conclusion

The need to provide funding that allows schools and districts to adequately meet the educational needs of ELs is not going away. As recent population trends show, this group of students continues to grow in terms of number[48] and diversity.[49] Our discussion provided a starting point for identifying the spectrum of approaches that could be used to refine funding systems to better serve the nation’s five million EL students. Most of the work will require a commitment from states and localities interested in reimagining how we define funding adequacy for ELs, how we measure and calculate the educational elements that promote EL success, and how we better integrate ELs into all aspects of state and district funding structures. Researchers, funding experts, practitioners, advocates, and even families should all be part of this process. ELs need access to educational services and programs that develop them into full participants in society, anything less falls short of fulfilling their civil rights.

Acknowledgments

- Brenda Calderon, special assistant in the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education in the U.S. Department of Education

- Maria Coady, professor of rural and multilingual education and a Goodnight Distinguished Professor in Educational Equity at North Carolina State University

- Indira Dammu, senior analyst at Bellwether

- Chris Duncombe, senior policy analyst at the Education Commission of the States

- Roxanne Garza, senior education policy advisor at UnidosUS (formerly the National Council of La Raza)

- Laura Hill, policy director and senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California

- Oscar Jiménez-Castellanos, director of P–12 research at the Education Trust

- Ajay Srikanth, former PhD graduate at the Graduate School of Education at Rutgers University, current researcher at American Institutes for Research

- Zahava Stadler, former special assistant for state funding and policy at Education Trust, current project director for the Education Funding Equity Initiative at New America

- Julie Sugarman, senior policy analyst for PreK–12 Education at the Migration Policy Institute’s National Center on Immigrant Integration Policy

I appreciate my New America colleagues Amaya Garcia, Elena Silva, and Zahava Stadler for their helpful feedback and edits. I am grateful to Sabrina Detlef for her editorial insight, and Fabio Murgia and Mandy Dean for their layout and communication support. New America’s PreK–12 team is generously supported by the Annie E. Casey Foundation, Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Carnegie Corporation of New York, Heising-Simons Foundation, William and Flora Hewlett Foundation, Joyce Foundation, and Walton Family Foundation. The views expressed in this report are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of these foundations.

- Leslie Villegas is a senior policy analyst with the Education Policy program at New America, where she focuses on the PreK–12 policy landscape for English learners. Her work focuses on incorporating an equity-and asset-based approach into federal and state education policy through accountability, assessment, funding, and other key policy areas. Inspired by her own experiences as a first-generation Mexican immigrant raised in California, Villegas believes equitable access to quality education is the key to creating a more fair, inclusive, and representative society.

This article was published by New America (https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/briefs/english-learner-funding-equity-and-adequacy-in-k12-education/) and is reprinted here under a Creative Commons license. Visit New America for more insightful coverage of current affairs.