A government decision in 2012 started an official dialogue offering Spanish citizenship to Sephardic Jews in compensation for their ancestor’s expulsion from Spain during the Spanish Inquisition. Citizenship will be granted to descendants of Sephardi Jews provided they hire a Spanish notary and pass exams on Spanish language and history. The tests will be administered by the Cervantes Institute, a Spanish government entity that conducts courses in Spanish culture and language, and offered in over 20 countries. “The procedure for acquiring Spanish nationality regulated in this law will be electronic,” the law reads. “The request will be in Spanish and will be overseen by the General Directorate of Registrars and Notaries.” Portugal recently passed a similar law that is more open-ended and does not require proven fluency in Portuguese.

A government decision in 2012 started an official dialogue offering Spanish citizenship to Sephardic Jews in compensation for their ancestor’s expulsion from Spain during the Spanish Inquisition. Citizenship will be granted to descendants of Sephardi Jews provided they hire a Spanish notary and pass exams on Spanish language and history. The tests will be administered by the Cervantes Institute, a Spanish government entity that conducts courses in Spanish culture and language, and offered in over 20 countries. “The procedure for acquiring Spanish nationality regulated in this law will be electronic,” the law reads. “The request will be in Spanish and will be overseen by the General Directorate of Registrars and Notaries.” Portugal recently passed a similar law that is more open-ended and does not require proven fluency in Portuguese.

Sephardic Jews Learn Spanish Language for Citizenship

Middlebury’s Language Schools Turn 100

The Middlebury Language Schools celebrate their 100th anniversary this year and will be celebrating with academic and festive events from July 15-19 at both their Vermont and California campuses. The German School was the first of Middlebury’s language consortium, and was founded in 1915, followed by the French and Spanish schools in 1916 and 1917, respectively. The program has grown to include Arabic, Chinese, German, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, and Russian. The centennial celebration also marks the official opening of the new School of Korean as Middlebury’s 11th language school. Bernadette Brooten from Middlebury’s School of Hebrew said, “It’s 100 years of attempts to build bridges across cultures in the midst of military and political turmoil, and the commitment to continue to do that.”

The Middlebury Language Schools celebrate their 100th anniversary this year and will be celebrating with academic and festive events from July 15-19 at both their Vermont and California campuses. The German School was the first of Middlebury’s language consortium, and was founded in 1915, followed by the French and Spanish schools in 1916 and 1917, respectively. The program has grown to include Arabic, Chinese, German, Hebrew, Italian, Japanese, Portuguese, and Russian. The centennial celebration also marks the official opening of the new School of Korean as Middlebury’s 11th language school. Bernadette Brooten from Middlebury’s School of Hebrew said, “It’s 100 years of attempts to build bridges across cultures in the midst of military and political turmoil, and the commitment to continue to do that.”

Dual Language Programs Benefit ELLs

Parents of English languages learners (ELLs) often place their children in English language based classroom in hopes that they will pick up the language, but bilingual education may be the better decision. A recent study by the Houston Education Research Consortium found that students learning English as a second language are more successful when they are continually taught in their native tongue. The study is one of the first solid results from the Houston International School District’s (HISD) two-way dual language program.

Parents of English languages learners (ELLs) often place their children in English language based classroom in hopes that they will pick up the language, but bilingual education may be the better decision. A recent study by the Houston Education Research Consortium found that students learning English as a second language are more successful when they are continually taught in their native tongue. The study is one of the first solid results from the Houston International School District’s (HISD) two-way dual language program.

Profile: Mohamed Abdel-Kader

With his basic Spanish and fluency in Arabic, Mohamed Abdel-Kader’s term as deputy assistant secretary in the office of International and Foreign Language Education (IFLE) at the U.S. Department of Education will be short but may be decisive

Since September of last year, Mohamed Abdel-Kader has overseen the International Foreign Language Education team at the U.S. Department of Education, managing two sets of grants: the Title VI programs, which invest largely in capacity at institutions across the country for less commonly taught world languages and world area studies, and the Fulbright Hays programs, which invest largely in small groups and individuals to help them study abroad and hopefully bring that fantastic experience back into the classroom or into whatever environment they operate in.

Mohammed is proud to have been born in New York City to two newlywed immigrants who had just graduated from college in Egypt. They were two young physics majors who had met in a physics lab and were very much in love and a few weeks after they got married, they chose to come to the U.S. instead of going to the UK, thanks to a friend.

Mohammed spent a lot of his childhood going back and forth between New York and Cairo, and early on, on the playground, he had to learn very quickly how to explain what was happening on the other side of the world. This was back in the early ’80s, when the Iran hostage crisis was still very fresh on a lot of people’s minds. “A lot of people said things that weren’t very flattering, but very quickly put me in a position where I had to learn about other parts of the world and articulate what was going on in a way that helped me not get beat up on the playground. It’s not always the most fun story to tell, but I always illustrate that even at an early age little kids are having to think about other parts of the world,” remembers Mohammed.

He also saw the other side of the coin: “When I’d go see my cousins in Egypt and I was playing soccer, folks would always ask me, ‘Well, what’s it like in America? Do you have a Ferrari? Do you have a Lamborghini? Do you run around with guns like Rambo?’ I had to explain to them that that wasn’t really the case either.” After a two-year stint at an international school in Saudi Arabia, he and his family moved back to Clemson, South Carolina, a few weeks before the start of the first Gulf War. So again, he quickly found himself having to explain what was happening on the other side of the world, this time as a seventh grader. “I didn’t always have the answers, but it forced me to dig in a lot.”

As a political science major, he became very interested in various parts of the world and the Middle East in particular. As he explored his heritage and tried to bridge the understanding gap, he realized that he had to articulate what he knew to be a reality on the other side of the planet and became inspired by the role of higher education. Involved in student government at Clemson, he got to work with the university’s leadership and see how a university like Clemson, a state-funded land grant, had an impact on economic development and on helping young kids, who in many cases had never been outside of a two-hour radius of their homes — especially because it encouraged study abroad.

After 9/11, Mohammed studied higher-education policy in graduate school and took an interest in the development of American institutions taking their products overseas. “I kept thinking to myself how powerful it would be if we took the land-grant model overseas into sub-Saharan Africa and what it would do for economic development, or what it would do in the Middle East, or what it would do in China or India and all these emerging economies. I was very excited by that idea and I was also very happy that my parents had insisted when I was a kid that we spoke Arabic at home, because as a kid I kicked and screamed and I was like, ‘Why do we have to be different? Why do we have to speak Arabic at home? Why can’t we speak English like all the other kids?’ But my parents insisted, and I didn’t know any better. Suddenly, I found myself in grad school, I spoke fluent Arabic, and a little bit of Spanish because I started early because we had a substitute teacher in the third grade who infused Spanish into our curriculum. Suddenly I had these tools, and it was really helpful. It was really making my life easier, and I found that I was so far ahead of so many of my peers who hadn’t spent the time acquiring these skills,” enthuses Mohammed.

He helped to develop George Mason University’s programs in the Emirates and South Korea and then moved to Georgetown University, where he continued to see the power of this interdisciplinary learning experience where a language, world area studies, and other disciplines like business, public health, and law were having an impact on society. “These students were leaving our campuses with the toolbox to operate in a sometimes ambiguous environment, and I found that to be just fascinating.”

Now, brought in at the tail end of the Obama administration, he has “a short runway to hopefully do a lot of things.” His operational plan has three “pillars,” the first of which is based around human capital and operations, building capacity on the team, and thinking about operations — how to make things more efficient and more effective. They’ve hired three new program officers and are planning to bring on a few more in the coming months.

The second pillar of the plan is focused on communication, because “I wholeheartedly believe that, generally speaking, we don’t do a great job of articulating the impact of what we do. We don’t tell our story. It’s important that we demonstrate impact. It’s important that we talk about the metrics of our success, but there’s a qualitative piece that I think sometimes we forget about, and what I’d like to do is mix the two together. I’m not going to get away from the quantitative impact, that’s important and we need to be able to measure certain things, but we also need to bring some life to these stories. Where are we falling short? Where are the kids who are falling through the cracks? Who are the kids that are doing really well? I want to hear the story about the kid, from Kansas who had never left an hour’s drive of his home and suddenly finds himself on a scholarship at a place like Ohio State, or Indiana, or Michigan, or Berkeley, and learns Mandarin. The next thing you know, this kid, who’s a finance major, is doing a deal for a bank in Shanghai. I think that’s a great story and we need to talk about that. We need to talk about the story of the young nurse who goes to school and learns another language and ends up in a hospital and is able to treat new immigrants to this country who don’t speak English, but she’s able to provide better patient care because she learned another language at her school. I keep telling my team we’ve got to think about the fact that our classrooms and our neighborhoods and our playgrounds all look different.

“These skills are not a ‘nice-to-have’ — in this town (Washington, DC) a ‘nice-to-have’ is not a good thing. We’ve got to be seen as an essential, and part of that is our storytelling and reframing. For many of us in this room who have drunk the Kool-Aid and believe in what we do, sometimes we take it for granted. I take it for granted all the time, like of course everybody should learn a couple foreign languages, but not everybody on Main Street gets it. Not every college student who’s 18 years old and maybe working a job or two, maybe at the Gap or maybe at the dining hall on campus, is taking out student loans and is maybe the first in the family to go to college, not every student is going to get there and stand in front of the registrar and say, ‘You know what, yeah, I’m going to spend twelve to 16 credit hours on a world language.’ Sometimes the benefit is not entirely clear to our students, and everybody in this room has to play a role in articulating why it’s important.”

Mohammed thinks it’s important to reiterate the President’s line about 95% of the world’s consumers being outside of U.S. borders and 75% of the people in the world not speaking English, despite it being the lingua franca of the business world. He points out that one in five American jobs are tied to international trade and that number is expected to grow, and depending on the state one lives in, that number is likely to be higher. So these skills are not a “nice-to-have,” they’re an essential, and “we’ve got to do a better job of telling that story.”

The last pillar in the roadmap is what he loosely calls innovation, “thinking a little more creatively around leveraging platforms that are out there. Leveraging investments that we’ve currently made, leveraging historical investments, looking for synergies within the ecosystem, and then also looking forward.” With talk of reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, Mohammed’s department is taking time to think a little bit more about the future of their program, talking to grantees, talking to partners and colleagues, and talking to the business community to get a sense of what skills that a person needs and how we need to prepare students for the workforce of tomorrow.

Mohammed and his team have their work cut out over the next few months. Follow their progress on Twitter at @goglobaled, where they also want to hear and share your stories.

This article is based upon a speech given by Mohamed Abdel-Kader to delegates at the JNCL–NCLIS Languages Advocacy Day on May 7, 2015, in Washington, DC.

English on the Upswing Among Latinos

According to a new report out by the Pew Research Center, English proficiency has hit all-time highs among Latinos, while Spanish is spoken less and less in Latino homes. The report, “English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos: U.S. Born Driving Language Change,” by Jens Manuel Krogstad, Renee Stepler and Mark Hugo Lopez, examines language use trends since 1980 among U.S. Latino populations based on U.S. Census data and American Community Surveys.

According to a new report out by the Pew Research Center, English proficiency has hit all-time highs among Latinos, while Spanish is spoken less and less in Latino homes. The report, “English Proficiency on the Rise Among Latinos: U.S. Born Driving Language Change,” by Jens Manuel Krogstad, Renee Stepler and Mark Hugo Lopez, examines language use trends since 1980 among U.S. Latino populations based on U.S. Census data and American Community Surveys.

Irish Revival Stalls

Irish language fluency was a requirement for anyone appointed to civil service positions in the Republic of Ireland until the Language Freedom Movement in 1974, which required proficiency in either of the country’s official languages (Irish or English). In 1985, a study commissioned by The Irish National Teachers’ Organization found that the public was almost evenly divided on whether or not the Irish language, also known as Gaelic, should be taught to children in public schools. Teachers were overall enthusiastic about including the language in their curriculum, but felt that the general public was not interested in its revival. In 2003, the Republic of Ireland’s government enacted the Official Languages Act, which promotes the use of the Irish language through mandating Irish language translations on all signs and documents and is part of a plan to have at least 250,000 speakers of Irish by 2030. The current estimate is between 40,000 and 80,000 native speakers. Hundreds of millions are spent each year trying to sustain the use of Irish, and just a few weeks ago President Michael D. Higgins made a request for the Irish people to do more for their language saying, “Déanaimis iarracht níos mó ar son na Gaeilge.”

Preserving the Critically Endangered N|uu Language

N|uu is the language of the San people, who were the first hunter-gatherers in southern Africa. The language has 112 distinct sounds including 45 characteristic “clicks” and has been passed down orally for generations. Due to its critically endangered state, linguists are working with the last three living speakers of N|uu to design alphabet charts in an effort to preserve the ancient African language. “It’s the most indigenous language of southern Africa,” Matthias Brenzinger, director of the Centre for African Language Diversity at the University of Capetown, told The Guardian. “Very often [white settlers] kept the young girls, but they killed all the men. Genocide is the major reason for these languages in southern Africa to be extinct now, and then forced assimilation. Farmers were taking their land so there was no subsistence for them any more.”

N|uu is the language of the San people, who were the first hunter-gatherers in southern Africa. The language has 112 distinct sounds including 45 characteristic “clicks” and has been passed down orally for generations. Due to its critically endangered state, linguists are working with the last three living speakers of N|uu to design alphabet charts in an effort to preserve the ancient African language. “It’s the most indigenous language of southern Africa,” Matthias Brenzinger, director of the Centre for African Language Diversity at the University of Capetown, told The Guardian. “Very often [white settlers] kept the young girls, but they killed all the men. Genocide is the major reason for these languages in southern Africa to be extinct now, and then forced assimilation. Farmers were taking their land so there was no subsistence for them any more.”

The Icelandic Language, Nationalism, and the Internet

In 2013, a paper by András Kornai entitled “Digital Language Death” estimated that only 5% of the world’s languages would ascend into the digital realm, and that the rest would die off in a massive language extinction. While this has greatly been true for many indigenous languages, the globalizing effects of the Internet and other English-language technologies have threatened the cultures of entire countries. Many countries have recently announced either resistance to or acceptance of the inclusion of English-language loan words, or Anglocisms, but in the case of Iceland, the Icelandic language may be entirely replaced by English.

In 2013, a paper by András Kornai entitled “Digital Language Death” estimated that only 5% of the world’s languages would ascend into the digital realm, and that the rest would die off in a massive language extinction. While this has greatly been true for many indigenous languages, the globalizing effects of the Internet and other English-language technologies have threatened the cultures of entire countries. Many countries have recently announced either resistance to or acceptance of the inclusion of English-language loan words, or Anglocisms, but in the case of Iceland, the Icelandic language may be entirely replaced by English.

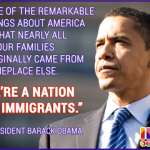

President Endorses Immigrant Heritage Month

This morning, President Obama devoted his weekly address to the celebration of Immigrant Heritage Month (#IHM2015), an occasion that allows us to celebrate our origins as a nation of immigrants, and vowed to push forward with immigration reform.

This morning, President Obama devoted his weekly address to the celebration of Immigrant Heritage Month (#IHM2015), an occasion that allows us to celebrate our origins as a nation of immigrants, and vowed to push forward with immigration reform.

“I think of growing up in Hawaii, a place enriched by people of different backgrounds – native Hawaiian, Filipino, Japanese, Chinese, Portuguese and just about everything else. Growing up in that vibrant mix helped shape who I am today. And while my father was not an immigrant himself, my own life journey as an African-American – and the heritage shared by Michelle and our daughters, some of whose ancestors came here in chains – has made our family who we are,” shared the President.

Language Magazine is also a proud supporter of Immigrant Heritage Month. “Immigrants, their cultures, languages, and skills are America’s greatest resource,” claims Language Magazine editor Daniel Ward. “In our age of globalization, we have to recognize the value of our multicultural, multinational roots and ensure that immigrants, old and new, retain and share the skills, customs, and knowledge that they brought to this country so that all Americans can have a better understanding of the global village in which we live.”

Language Magazine is inviting its readers and followers to share their own immigration stories, publicize their heritage culture and language programs, and announce events through our network. Visit our story submission page for details on how to submit information.

The basic idea of welcoming people to our shores is central to our ancestry and our way of life so the President is also asking everyone to visit whitehouse.gov/NewAmericans and share stories of making it to America.

Let’s celebrate our immigrant heritage!