|

Immigration is one of the most complex phenomena of our current century. There are many reasons why people, either voluntarily or involuntarily, leave their homelands for the purpose of residing in a foreign land. Research suggests these reasons are divided into “push” and “pull” factors (Bista and Foster, 2011; Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002). Some of the reasons people are pushed away from their countries of origin include wars, political unrest, poverty, natural disasters, gender inequality, and lack of healthcare or employment opportunities. Some of the factors pulling new waves of immigrants into countries include better chances of pursuing higher education, economic growth, greater security, and quality of life. These underlying reasons contribute to there being approximately 272 million current migrants worldwide, with the number increasing significantly every year (United Nations, 2020).

The first generation of these new settlers faces various obstacles such as racial discrimination and limited access to local services, housing, and employment options, as well as language barriers and cultural differences, which also affect the following generations. As research shows, regardless of the country of origin, many immigrant families often struggle with raising families in a language and culture that is still foreign to them while maintaining the desire to hold on to their roots and traditions (Ashtari, 2020; Krashen, et al., 2020). As the children of immigrant families grow up in this new world inside and outside of the household, they are also faced with the challenge of trying to merge this dichotomy and shape their own identities while defining their hyphenated social markers, such as Iranian-American, Chinese-American, Japanese-American, Korean-American, Arab-American, and so forth.

Unfortunately, this inner and outer battle of identities is a long and exhausting one that, according to research, more often than not results in the loss of the heritage language and culture even within one or two generations (Crawford, 1992; Krashen et al., 1998). A heritage language is defined as the language of the parents and ancestors that is not spoken by the dominant culture where the immigrants currently reside (Krashen, 1998).

There are approximately 430 heritage languages (or HLs) in the US, and more than 200 and 300 HLs in Canada and Australia respectively. According to Schumann (1978; 1986) there are ways to predict and explain how language learners acculturate to the target language group in their new countries. His acculturation model considers multiple social and psychological factors that play roles in determining the degree to which immigrants acculturate to the new language and culture.

One of these factors is the social dominance pattern, which states that if the native language and culture of the immigrants is deemed to be politically, economically, technologically, and culturally “inferior” (by personal, local, or global perceptions, news portrayals, etc.), a social distance between the two groups is created, and as a result there will be resistance to learning the heritage language.

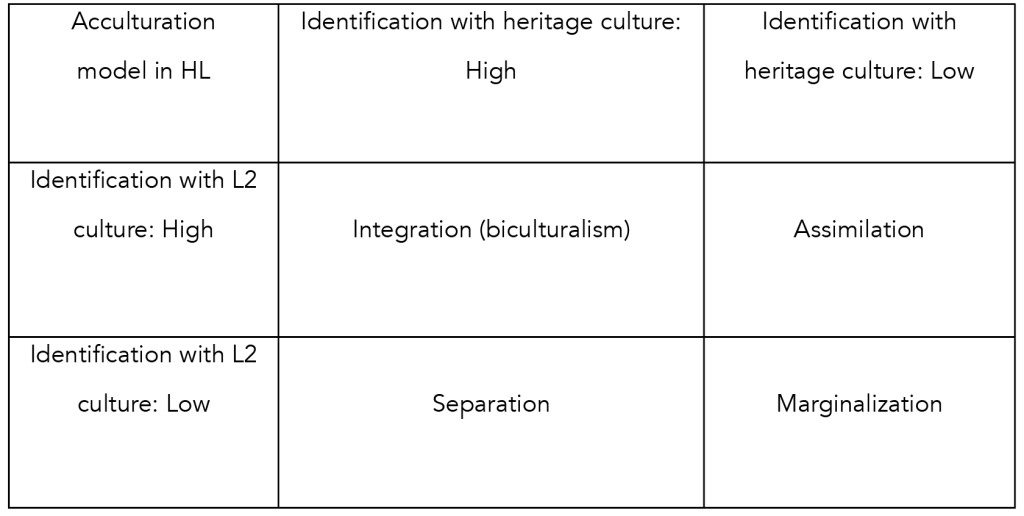

Schumann (1986) and Berry (1997) discuss various integration patterns when it comes to immigrant populations: assimilation, preservation, adaptation, and marginalization.

In assimilation, the immigrant gives up their language/culture of origin and identifies and interacts mainly with the new culture. When it comes to preservation or separation, the person maintains their first language (L1) and culture of origin and rejects those of the L2 group. In adaptation, also known as integration or biculturalism, the person keeps and uses both their L1 and the language that is spoken in their new country. There is, however, a sense of total isolation and alienation in marginalization, when the person does not identify with either their L1 or L2 group.

Immigration is one of the most complex phenomena of our current century. There are many reasons why people, either voluntarily or involuntarily, leave their homelands for the purpose of residing in a foreign land. Research suggests these reasons are divided into “push” and “pull” factors (Bista and Foster, 2011; Mazzarol and Soutar, 2002). Some of the reasons people are pushed away from their countries of origin include wars, political unrest, poverty, natural disasters, gender inequality, and lack of healthcare or employment opportunities. Some of the factors pulling new waves of immigrants into countries include better chances of pursuing higher education, economic growth, greater security, and quality of life. These underlying reasons contribute to there being approximately 272 million current migrants worldwide, with the number increasing significantly every year (United Nations, 2020).

The first generation of these new settlers faces various obstacles such as racial discrimination and limited access to local services, housing, and employment options, as well as language barriers and cultural differences, which also affect the following generations. As research shows, regardless of the country of origin, many immigrant families often struggle with raising families in a language and culture that is still foreign to them while maintaining the desire to hold on to their roots and traditions (Ashtari, 2020; Krashen, et al., 2020). As the children of immigrant families grow up in this new world inside and outside of the household, they are also faced with the challenge of trying to merge this dichotomy and shape their own identities while defining their hyphenated social markers, such as Iranian-American, Chinese-American, Japanese-American, Korean-American, Arab-American, and so forth.

Unfortunately, this inner and outer battle of identities is a long and exhausting one that, according to research, more often than not results in the loss of the heritage language and culture even within one or two generations (Crawford, 1992; Krashen et al., 1998). A heritage language is defined as the language of the parents and ancestors that is not spoken by the dominant culture where the immigrants currently reside (Krashen, 1998).

There are approximately 430 heritage languages (or HLs) in the US, and more than 200 and 300 HLs in Canada and Australia respectively. According to Schumann (1978; 1986) there are ways to predict and explain how language learners acculturate to the target language group in their new countries. His acculturation model considers multiple social and psychological factors that play roles in determining the degree to which immigrants acculturate to the new language and culture.

One of these factors is the social dominance pattern, which states that if the native language and culture of the immigrants is deemed to be politically, economically, technologically, and culturally “inferior” (by personal, local, or global perceptions, news portrayals, etc.), a social distance between the two groups is created, and as a result there will be resistance to learning the heritage language.

Schumann (1986) and Berry (1997) discuss various integration patterns when it comes to immigrant populations: assimilation, preservation, adaptation, and marginalization.

In assimilation, the immigrant gives up their language/culture of origin and identifies and interacts mainly with the new culture. When it comes to preservation or separation, the person maintains their first language (L1) and culture of origin and rejects those of the L2 group. In adaptation, also known as integration or biculturalism, the person keeps and uses both their L1 and the language that is spoken in their new country. There is, however, a sense of total isolation and alienation in marginalization, when the person does not identify with either their L1 or L2 group.

The Next Generation

As shown in the table below for the next generations of these immigrants, if the heritage-language group identifies highly with the culture of their current country as well as their country of family origin, we then get the ideal linguistic situation of integration and bilingualism/biculturalism. If, however, the identification with the heritage culture is low but identification with the current culture and language is high, then we get assimilation, which results in giving up the heritage language and culture.

The Ethnic Identity Formation Model

Tse (1998) also describes an ethnic identity formation model that paints a picture of how the next generation of ethnic minorities can adapt their identities throughout their lifetimes. The ethnic identity formation model explores four different stages: unawareness, ethnic ambivalence/evasion, ethnic emergence, and ethnic identity incorporation. In the unawareness phase, children of ethnic minorities are not aware of their minority status and see themselves as part of the dominant culture and not different from others.

During the ethnic ambivalence/evasion phase, they develop ambivalent or negative feelings toward their ethnic culture; this usually occurs during adolescence and early adulthood. Ethnic emergence is when these individuals become more curious and begin exploring their ethnic heritage and language, which can sometimes but not always lead to the final stage, ethnic identity incorporation.

During this final stage, they are more open to joining the ethnic minority group within the bigger dominant group and resolve their ethnic identity conflicts by accepting both of their identities. The following is a quote by a Persian bookstore owner in Los Angeles (the city with the largest population of Iranians abroad) that depicts these stages when it comes to Iranian-American families in the US:

“When they get older is when they usually come in. They go to graduate school at UCLA or another university in their 20s and 30s. They realize that they can’t speak their mother tongue; that’s when they start coming to get books or take Farsi classes. They realize that a piece of them is missing” (Ashtari, 2020).

What Can We Do?

Smith (1988) hypothesized that for successful literacy development, children need to consider themselves as potential readers and writers, or potential members of the “literacy club.” Similarly, according to Krashen (2008), language acquisition accelerates when acquirers consider themselves as potential members of the group that uses the target language: “When we join a club, or at least feel that we are welcome to join, the affective filter goes down and we acquire those aspects of language that mark us as members of the group that uses that language” (Krashen, 1997). In order for us to achieve more bilingualism and biculturalism when it comes to heritage language learners, we can take simple steps to bring these students’ rich and exceptional backgrounds to the foregrounds of our instruction and teaching activities for them to feel more like potential members of the heritage language club.

Researching the Heritage Language and Culture

One of the main challenges of heritage-language acquisition when it comes to immigrant populations is the next generation not feeling fully connected to their heritage language and culture.

By having some informal research and exploration opportunities into their heritage language and culture or even sharing the topics of HL languages and cultures among the students in a class and then having them present their findings in the media of their choice, we can develop healthy and enjoyable information-sharing experiences and connections among our students as they get to know more about their heritage languages and cultures. Creating “culture corners” in the classroom is another option, where students bring photos, maps, artifacts, realia, or even food from their heritage cultures to share, enjoy, and learn from and with each other.

Learning More about Family History

Exploring identities, accepting oneself as an ethnic minority, and improving one’s self-image are other stumbling blocks for HL acquirers. One option is to provide opportunities for students to be able to investigate their own family histories and ancestral trees.

They can conduct informal interviews with their own family members to learn more about their histories, memories from the homeland, and the ups and downs of immigration. They can share what they learn in a variety of ways, either with other students in class or privately as journal writing or short stories. If some students are not comfortable with researching, interviewing, and writing about their own families, they can choose a prominent figure or any person of their choice from their heritage culture to focus on. These strategies can help with the ethnic emergence and ethnic identity incorporation phases of the ethnic identity formation model (Tse, 1998) described earlier.

Having Virtual Tours of the Home Countries

Technology gives us an advantage when it comes to more creative content from around the world, either produced informally by individual travelers or officially by professional companies and businesses. There are a variety of videos and virtual applications available online that create interesting and entertaining input and interactive environments for heritage-language acquirers to explore, even if they cannot go to their heritage countries in person. These kinds of compelling input not only provide an abundance of knowledge about different countries/languages/cultures but also supply captivating visual representations that can help with identifying and connecting with heritage languages and cultures.

Teaching a Word or Phrase of the Day

Docendo discimus is a Latin proverb meaning “by teaching, we learn,” or what Vygotsky called “less capable peer” teaching (Vygotsky, 1978). When students work together to teach each other, they collectively create a bond as they try to understand and explain words and phrases in their heritage languages to each other, and both sides simultaneously expand their knowledge. This exchange of words and phrases of the day also aids them in building higher respect and appreciation for their respective heritage languages and cultures.

Using Popular Literature and Media from Home Countries

Henkin and Krashen (2015) discuss the importance of using popular literature, including comic books and graphic novels, in second-language acquisition. Self-selected, compelling, comprehensible input lays the foundation for acquiring languages. Popular literature and media from home countries can be excellent tools for combining entertainment and optimal input.

The optimal input hypothesis claims that optimal input needs to be:

comprehensible,

compelling,

rich, and

abundant (Krashen, 2020; Mason and Krashen, 2020).

Choosing topics and modes of input that are interesting to students enables them to find materials that meet all or most of the criteria above, enjoy them, and gain more information about their heritage languages and cultures at the same time. This can be in the form of a few minutes of free reading in class or activities such as watching movies or TV shows.

Conclusion

There are many ways we can go about incorporating our students’ heritage languages and cultures in our classrooms. In this paper, we mentioned five of them: researching their heritage languages and cultures, learning about their family histories, having virtual tours of the home countries, teaching words or phrases of the day, and using popular literature and media from their home countries.

By creating more opportunities for our students to explore their own identities and learn about their own histories, we can help them to become proud members of their own heritage language and culture clubs. They can bring their unique paths into the foreground and paint more colorful pictures of their backgrounds, connect more with their familial roots, and learn more about each other and the beauty of the diversity of the world that we live in. After all, we are all members of the same humanity club, and in the words of Maya Angelou, “we can learn to see each other and see ourselves in each other and recognize that human beings are more alike than we are unalike.”

References

Ashtari, N. (2020). “Heritage Language Classes: The case of Farsi.” NABE Global Perspectives, 44(2), 5–7.

Ashtari, N. (2020). “Reaching Rumi: The accessibility and comprehensibility of Farsi reading materials for heritage language learners.” Language Magazine, 19(9).

Berry, J. (1997). “Immigration, Acculturation, and Adaptation.” Applied Psychology, 46(1), 10.

Bista, K., and Foster, C. (2011). “Issues of International Student Retention in American Higher Education.” International Journal of Research and Review, 7(2), 1–10.

Crawford, J. (1992). Hold Your Tongue: Bilingualism and the Politics of “English Only.” Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Henkin, V., and Krashen, S. (2015). “The Naruto Breakthrough: The home run book.” Language Magazine, 15(1), 32–25.

Krashen, S. (1997). Foreign Language Education: The Easy Way. Language Education Associates.

Krashen, S., Tse, L., and McQuillan, J. (1998). Heritage Language Development: Some Practical Arguments. Culver City, CA: Language Education Associates.

Krashen, S. (2008). “The Comprehension Hypothesis Extended.” In T. Piske and M. Young-Scholten, Input Matters in SLA, Multilingual Matters, pp. 81–94.

Krashen, S., Lu, H., and Ashtari, N. (2020). “Heritage Language Development: Expectations and Goals.” Chinese Language Teaching Methodology and Technology Journal, 3(1), 1–3.

Krashen, S. (2020). “Optimal Input.” Language Magazine, 19(3), 29–30.

Mason, B., and Krashen, S. (2020). “The Optimal Input Hypothesis: Not all comprehensible input is of equal value.” CATESOL Newsletter, May 19, 1–2.

Mazzarol, T., and Soutar, G. (2002). “The Push-Pull Factors Influencing International Student Selection of Education Destination.” International Journal of Educational Management, 16, 82–90.

Schumann, J. (1978). The Pidginization Process: A Model for Second Language Acquisition. Newbury House Publishers.

Schumann, J. (1986). “An Acculturation Model for Second Language Acquisition.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 7, 379–392.

Smith, F. (1988). Joining the Literacy Club. Heinemann.

United Nations (2020). International Migration Report. Department of Economic and Social Affairs. https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/sites/www.un.org.development.desa.pd/files/undesa_pd_2020_international_migration_highlights.pdf

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Harvard University Press.

Nooshan Ashtari, PhD, has spent the last two decades teaching languages and graduate/undergraduate courses and conducting research in various countries around the world. She believes in fairness. Once, in a Taekwondo competition, she was yelled at furiously by her coach because she thought her opponent had excellent technique and deserved to win.