|

Margarita Calderón and Shawn Slakk believe that the whole school is responsible for the success of English learners

English learners (ELs) are no longer solely the responsibility of the ESL teacher. The entire school’s staff of educators—counselors, secretaries, and of course administrators included—should embrace the success of ELs along with all their peers. Leadership teams are deliberately deciding to focus the majority of their staff development days, professional learning communities (PLCs), teacher learning communities (TLCs), and coaching efforts on the success of English learners. To start, they reanalyze ELs’ placement and success trajectories, in order to chart changes in staffing, school schedules, and teacher and student support systems.

Schools that are concerned with their EL underachievement and have tried different English learner development/English as a second language (ELD/ESL) strategies and programs without seeing progress have come to realize that the best thing to do is to prepare every educator in the school to adjust practices. Since everyone is already anticipating changes forthcoming from Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) accountability, a deeper dive into EL success makes sense at this time.

Fortunately, we are working with schools that have implemented the whole-school approach in the past few years, and we have mapped out their trajectories. Although we see this whole-school approach take hold at different points, the components are always the same. In this article, we highlight those components and how schools move forward on each.

The Common Factors and Components

First, for ALL educators in the school, schedule the same professional development (PD) focusing on teaching ELs and then other types of PD;

Following the PD on ELs, establish the support systems immediately: in-class and peer coaching for those directly teaching ELs in all subjects, PLC/TLC focus groups on EL data and success, and administrator observations;

Additionally, use multiple levels of data to review ELs’ placement, coordinate tweaks/repairs to the process, and ensure adequate staffing based upon EL service needs;

Successively, update schedules and staff to address the diversity of EL proficiency/educational levels;

Likewise, review, revise curriculum, and hire additional staff as needed for newcomers, students with interrupted formal education (SIFEs), and long-term ELs;

Furthermore, engage families—revisit forms sent home and primary language needs and focus on improving communications;

Continuously, build safe, caring self-actualization contexts in classrooms and on campus.

Professional Development for ALL

Schools and school divisions schedule the professional development on ELs’ success before any other PD. They set aside those days, especially when the school only has a few precious days for PD. This emphasis sets the tone and works to ensure that the PD will take place and that everyone will attend. The scheduling is sometimes modified, but the intent is sustained. For example, in Loudoun County Public Schools, Virginia, Simpson Middle School and Loudoun County High School began by offering the PD on ELs for half the faculty in year one and the other half in year two. From the start, the principals, assistant principals, supervisors, instructional coaches, and district central office specialists attended with the first cohort of teachers. In addition to attending the professional development on teaching academic language/vocabulary/discourse, reading comprehension/close reading, and writing, revising, and editing for ELs, the administrative team attended an additional training for administrators on instituting implementation and teacher-support systems.

When considering what type of PD and why to include all educators, federal guidelines provide the answer. “Necessary personnel includes teachers who are qualified to provide EL services, core-content teachers who are highly qualified in their field as well as trained to support EL students, special education-ESL/ELD teachers for dually identified students, and trained administrators who can evaluate these teachers” (U.S. Department of Education, January 2015).

The PD focusing on EL success needs to intensively focus on all components of language and literacy acquisition. We conduct these trainings in several states and school districts around the country. Below is a sample agenda for the initial training for all educators, teachers and administrators alike:

Day 1 – Vocabulary Acquisition and Discourse: Why academic language? What is academic language? Which vocabulary do we choose? How do we preteach vocabulary/discourse before reading, then supplement during reading and after reading? How do we assess vocabulary?

Day 2 – Reading Comprehension for Content Acquisition: Teaching reading comprehension, text features and structures, and close reading of different types of texts, after reading anchoring strategies and performance and acquisition assessment.

Day 3 – The Writing Process for ELs: Drafting, revising, and editing from the content. Assessing different levels of proficiency based on and from subject-matter content.

Day 4 – (Optional) Classroom Structures: For ample student interaction, social emotional competencies, and cross-cultural understanding (Calderón et al, 2016).

Notice that these trainings are focused on literacy and language. While we primarily provide PD in English for ELs, we also train bilingual staff in Spanish for bilingual schools in New York City. In addition to the intensive focus on success for all ELs (or language learners), schools and various state departments of education recently began to implement similar trainings focusing on newcomers along with the general EL population.

After the initial training, administrators, supervisors, and coaches need to receive additional training to support and sustain the staff and ensure transfer to the classroom. “Administrators who evaluate EL program staff need to be adequately trained to meaningfully evaluate whether EL teachers are appropriately employing their training in the classroom for the EL program model to successfully achieve its educational objectives,” advises the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Civil Rights and the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, Educational Opportunities Section in their “Dear Colleague Letter” (January 2015).

The Basic Version of This Additional Training

Day 1 – Coaching vs. Evaluation: Why coaching? What are the tools to conduct observations and give feedback on vocabulary/discourse, reading comprehension, and writing for ELs? What constitutes evidence of successful implementation and transfer of strategies from PD to the classroom? How do we structure, schedule, and monitor peer coaching?

Day 2 – Support Systems: What structures support implementation? How do we structure activities for teacher support as they encounter instructional challenges? How do we structure, schedule, and monitor the TLCs and PLCs?

Implementing Support Systems

All those taking part in the PD should participate in the support system’s establishment and sustainability. Again, turning to the federal guidelines provides the answer. “Schools must provide adequate professional development and follow-up training in order to prepare EL program teachers and administrators to implement the EL program effectively” (2015).

Teachers need to receive coaching by master coaches, administrators, and instructional support staff, plus conduct peer observations and self-reflective observations. Continuing the example from Virginia, the follow-up to the teachers’ and administrators’ PD in Loudoun County schools consisted of 26 days for us, the PD providers, to coach the teachers who had attended. As the trainers observed teachers in their classrooms, the WISEcard, our observation protocol, was used to coach each teacher and analyze data on the frequency and quality of implementation. The administrative team shadowed the trainers each time they conducted observations and feedback sessions. Next steps were written for the teachers and administrators after each visit, inclusive of teacher goals and administrator supporting goals.

Well-crafted support systems include refinement and revision of strategies and time for teachers to share lessons and implementation. For instance, in Albemarle County Public Schools, Charlottesville, Virginia, and Shelby County Schools, Memphis, Tennessee, they have held “renew, revise, and refresh” sessions for those who attended the initial training. These sessions add to the basic set of strategies as well as allow teachers to work with the experts who provided the initial training to refine the implementation of their lessons. They work with school and grade-level colleagues to analyze and revise lessons and implementation and assess ways to infuse even more academic language and literacy success for ELs into their subjects and lessons.

Revamping the Infrastructure of the School

Some schools find that they have to simultaneously address professional development and infrastructure. In another school district, we were asked to help with the following tasks, all focusing on EL success:

Revisiting the identification of EL students; charting their diversity (newcomers, SIFEs, students with limited or interrupted formal education, long-term ELs) for appropriate placement;

Providing dually certified ELs, those who receive special education services in addition to ESL services, with both types of services and hours equally—one does not supersede the other;

Mapping implications for scheduling, service, and staffing updates;

Revising ELs’ direct service hours/schedules to comply with federal requirements;

Analyzing existing school plans and making suggestions for updating;

Reviewing and acquiring curriculum for the diversity of ELs;

Building a safe, caring, and resilient context for all ELs;

Engaging families and community organizations.

Federal regulations as outlined by the U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Civil Rights (USDOJ) currently require that ELs receive specific instructional services and specific hourly allocations for language development. For instance, ELs who have been assessed and found to be levels one and two on the WIDA ACCESS test (see www.WIDA.us) or a similar English-proficiency-level assessment should receive two class periods of ELD/ESL each day. ELs who are level three need one period of ELD/ESL per day. Students at levels four and five should receive one period at least three times a week, one class period being no shorter than 45 minutes. The remainder of the day for all ELs should be in core content classes with teachers who have been certified or endorsed with special credentials for teaching structured English language and content to ELs. Some states, such as Massachusetts, require all core content teachers to go through graduate-level coursework similar to what Virginia schools are using in order to renew, advance, or even obtain their teaching credentials to teach in Massachusetts. This requirement includes administration too.

The whole-school approach meets the USDOJ requirement that ELs must have equitable access to grade-level content, enabling them to meet college- and career-readiness standards. Districts are obligated to ensure that ELs have equal opportunity to participate in all programs—academic or otherwise—including but not limited to prekindergarten, magnet, gifted and talented, career and technical education, arts, and athletics programs; Advanced Placement courses; STEM/STEAM; clubs; and honors societies. Instruction and programing for ELs must reach the students where they are and build their language and literacy through content. This instruction must include all programs a school offers, supplemental or not (USDOE Tool Kit, 2016). Embracing a whole-school approach from here on satisfies all these guidelines.

Adequate Staffing

The USDOJ’s guidelines also emphasize “recruiting, developing, and retaining excellent educators as essential in order to ensure that EL program models successfully achieve their educational objectives. Local Educational Agencies (LEAs) must hire an adequate number of ESL/ELD teachers who are qualified to provide EL services and core-content teachers who are highly qualified in their field as well as trained to support EL students.”

While reviewing programs, schedules, service hours, and English learner needs, some districts have realized that they need additional staff and are working hard to fill those positions. In the interim, core teachers who have been trained in strategies for teaching ELs using their subject’s content help to bridge this gap and foster growth across the school. Shelby County Schools in Memphis, Tennessee, has gone one step further—this year, district office central administrators will be convening a cadre of trainers who will specialize in supporting the district in professional development based upon the intensive three-day training described earlier. Their goal is to supplement continuing outside professional development sessions and support those already trained in the components of teaching ELs while teaching their individual subjects. In addition, Shelby has started their third group of general education teachers and administrators in the same PD focused on successful teaching for ELs.

Below is a checklist based upon the above information and the guidelines from the USDOJ and USDOE. As a quick assessment, ask yourself:

Are our EL services and programs educationally sound in theory and effective in practice to meet the needs of each of our students?

Does our EL program enable ELs to attain both English proficiency and parity of participation in all aspects of our school/district’s instructional program within a reasonable length of time?

Does our school/district offer ELs sufficient services and programs until our ELs are proficient in English and can participate meaningfully in educational programs without EL support?

Does our level of service comply with the DOJ’s minimum suggested hours of service based upon each student’s ELD level and progress?

Does our program support and assist our ELs to fully engage at the same level of education as their non-EL peers, helping them to become college, career, and culturally ready?

For our dually identified ELs, does our program and level of service dovetail with appropriate special education services and related services at an equal degree of service, without one dominating the other?

As educators move toward new, uncharted challenges, engaging the whole school in this endeavor will facilitate positive changes and positive growth in students.

References:

Calderón, M.E. and Slakk, S. (2016). Expediting Comprehension for English Language Learners (ExC-ELL) Foundations Manual. Washington, DC: Margarita Calderón and Associates.

U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, and U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. (January 2015). “Dear Colleague Letter: English learner students and limited-English-proficient parents.” Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/letters/colleague-el-201501.pdf.

U.S. Department of Education. (November 2016). Tools and resources for providing ELs with a language assistance program. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/ellresources.html.

The U.S. Department of Education released a non-regulatory guidance (NRG) about ELs and Title III of ESEA that is available at http://www2.ed.gov/policy/elsec/leg/essa/essatitleiiiguidenglishlearners92016.pdf. The text of ESEA, as amended by ESSA, can be found at http://www2.ed.gov/documents/essa-act-of-1965.pdf.

Dr. Margarita Calderón, professor emerita Johns Hopkins University, serves on national preschool–12th literacy panels and advisory boards (National Research Council, ETS, WIDA, National Center for Learning Disabilities, National Literacy Panel for Language Minority Children and Youth). She is a consultant for the U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division. Her research interest focuses on professional development, effective schools, and language and literacy development of English language learners. She has been a middle and high school teacher and has taught bilingual and educational leadership courses at the University of Texas, El Paso; San Diego State University; and University of California, Santa Barbara. She has over 100 publications, is an international speaker, is invited to give keynote speeches at major conferences, and conducts comprehensive professional development programs throughout the country.

Shawn Slakk is vice president of operations, director of trainers, a senior consultant, and a master coach at Margarita Calderón and Associates. He was Massachusetts’ Department of Elementary and Secondary Education coordinator of the Rethinking Equity in the Teaching of English Language Learners (RETELL) initiative, has taught ESL and Spanish, and has been a school administrator.

On April 11, the U.S. Postal Service will release the16th stamp in the Distinguished Americans series, honoring Robert Panara (1920-2014), an influential teacher and a pioneer in the field of Deaf Studies. He inspired generations of students with his powerful use of American Sign Language to convey works of literature. At age ten, Panara was profoundly deafened after contracting spinal meningitis, which damaged his auditory nerves.

On April 11, the U.S. Postal Service will release the16th stamp in the Distinguished Americans series, honoring Robert Panara (1920-2014), an influential teacher and a pioneer in the field of Deaf Studies. He inspired generations of students with his powerful use of American Sign Language to convey works of literature. At age ten, Panara was profoundly deafened after contracting spinal meningitis, which damaged his auditory nerves. Denise Murray examines the future of the TESOL profession in preparation for next month’s international summit

Denise Murray examines the future of the TESOL profession in preparation for next month’s international summit

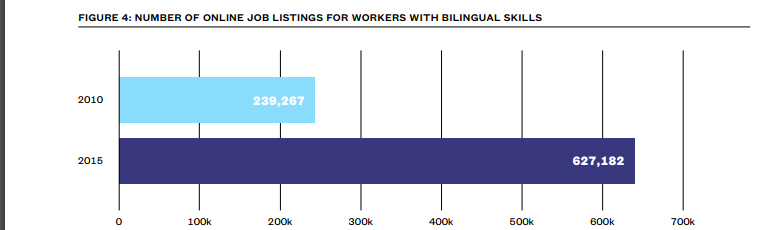

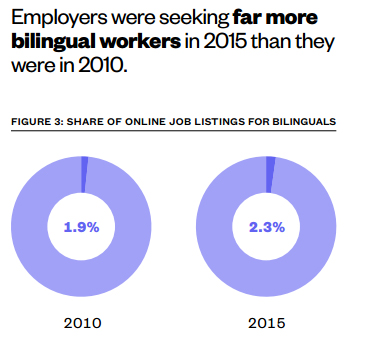

The types of employers varied depending on the languages they were seeking. The top three companies seeking Spanish-speakers were Advance Auto Parts, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America; for French they were International Services Incorporated (an insurance brokerage), Trinity Health, and the Peace Corps; Chinese listings were topped by Wynn Resorts, Bank of America, and Grifols (a pharmaceutical company); for Arabic the top listings were International Rescue Committee, Asi Constructors, Inc, and Lend Lease (a project management company). Across the board, demand for bilingual workers is especially high in certain industries like finance and healthcare.

The types of employers varied depending on the languages they were seeking. The top three companies seeking Spanish-speakers were Advance Auto Parts, Wells Fargo, and Bank of America; for French they were International Services Incorporated (an insurance brokerage), Trinity Health, and the Peace Corps; Chinese listings were topped by Wynn Resorts, Bank of America, and Grifols (a pharmaceutical company); for Arabic the top listings were International Rescue Committee, Asi Constructors, Inc, and Lend Lease (a project management company). Across the board, demand for bilingual workers is especially high in certain industries like finance and healthcare. University of Virginia linguistic anthropologist Mark A. Sicoli and colleagues are applying the latest technology to an ancient mystery: how and when early humans inhabited the New World.

University of Virginia linguistic anthropologist Mark A. Sicoli and colleagues are applying the latest technology to an ancient mystery: how and when early humans inhabited the New World.

nds on mobile phones. While these tech super-giants are in a heated competition to close in the voice-assist market, Siri has the advantage of being able to speak 21 languages localized for 36 countries. The latest, Shanghainese, is a variety of Wu Chinese spoken in central districts of the City of Shanghai and its surrounding areas. This Sino-Tibetan language, like many other Wu variants, is able to be understood outside of the Wu region by speakers of other languages such as Mandarin.

nds on mobile phones. While these tech super-giants are in a heated competition to close in the voice-assist market, Siri has the advantage of being able to speak 21 languages localized for 36 countries. The latest, Shanghainese, is a variety of Wu Chinese spoken in central districts of the City of Shanghai and its surrounding areas. This Sino-Tibetan language, like many other Wu variants, is able to be understood outside of the Wu region by speakers of other languages such as Mandarin.