Dr. Kate Kinsella offers evidence-based instructional practices to advance students’ verbal and written command of critical words

Dr. Kate Kinsella offers evidence-based instructional practices to advance students’ verbal and written command of critical words

Vocabulary Knowledge and Overall Academic Achievement

Vocabulary plays a crucial role in all aspects of academic competence in K–12 schooling. Certainly, one of the most consistent findings in reading research is the extent to which students’ vocabulary knowledge directly supports their reading comprehension (Baumann and Kaméenui, 2004; Graves, 2006). In the primary grades, native speakers of English who have a vast number of words in their oral vocabularies can more efficiently sound out and recognize familiar words as well as comprehend and appreciate text passages. As students progress to the upper grades and tackle more varied and challenging narrative and informational selections, vocabulary range and complexity strongly influence text readability (Chall and Dale, 1995).

Native speakers of English with anemic school-based vocabulary and weak verbal abilities struggle with reading and related writing tasks, contributing to disappointing overall academic achievement beyond the primary grades (Biemiller,1999;

Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998). If words are not in children’s verbal repertoire, those children understandably have trouble mapping sounds to words in print and accessing relevant background knowledge as they move from relatively accessible narrative selections to a range of complex texts across subject areas (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Research focused on school-age English learners similarly correlates vocabulary knowledge with second-language reading comprehension and other measures of school success, including high-stakes test scores and writing proficiency (August and Shanahan, 2006; Carlo et al., 2005). In fact, depth of word knowledge proves to be the most reliable predictor of English learner academic achievement across grade levels and curriculum (Marzano, 2004; Saville-Troike, 1984).

Economics and Word Prowess

Economics has an undeniable impact on a preschool youth’s early vocabulary enrichment and school readiness. A preschooler entering kindergarten from a college-

educated, professional household is likely to recognize and readily use twice as many words as a classmate from a non-college-educated, working-class family. Of greater concern, the child with parents who have completed an advanced degree typically crosses the kindergarten threshold with quadruple the vocabulary base of a child from a welfare family (Flynn, 2006).

Since growing up in under-resourced households can seriously restrict children’s daily vocabulary exposure and usage, bolstering their command of words for social and academic contexts is an instructional imperative (Hart and Risley, 2003; Snow, 1991).

Receptive and Productive Knowledge

Knowledge of word meanings can be classified as productive or receptive. Productive vocabulary is the working set of words we use comfortably and regularly when speaking and writing. Receptive vocabulary is a broader spectrum of words we recognize in specific contexts or at least partially understand when listening or reading. A person’s command of individual words falls on a virtual continuum of understanding. Dale (1965) proposes four levels to characterize the extent of an individual’s word knowledge: (1) have never seen or heard the word before; (2) recognize the word, but don’t know what it means; (3) have partial understanding of the word and readily associate it with a topic or concept; (4) know the word well and can explain it and skillfully use it. We develop incremental knowledge of a word as we encounter it again with new contexts and word partners—other words that commonly accompany the target word.

What “Owning” a Word Implies

To actually “own” a word means, in fact, to know a great deal about it. To perform adeptly on contemporary assessments requiring complex text analysis and evidence-based constructed responses, students must recognize a critical mass of vocabulary and be able to competently deploy a toolkit of high-utility academic words they clearly own. Nation (1990) analyzed the layers of complexity involved consciously or unconsciously in truly knowing—not just recognizing—a word, including its spoken and written forms.

To illustrate, review Table 1 and consider what is implied in having an agile verbal and written command of the high-utility academic word analysis. For a middle school team to apply the word analysis in a formal science report in a sentence like the following, the young scholars require a wealth of conscious lexical knowledge: After a thorough analysis of the nutrition label, we determined that the fruit snack was unhealthy because it contained artificial coloring, sodium, and high-fructose corn syrup.

Table 1: In-Depth Word Knowledge: Analysis

Pronunciation: a • nal • y • sis

Spelling: a-n-a-l-y-s-i-s

Part of Speech: noun

Meaning: a careful study of something to better understand it or find out what it contains

Synonym: study; examination

Antonym: none

Register: It is primarily used in formal academic and professional communication.

Frequency: It is not commonly used in casual conversation or correspondence, but it is frequently used in formal academic and professional contexts.

Collocations (Word Partners): It is commonly used in tandem with the verbs conduct and offer and the adjectives careful, close, in-depth, and thorough.

Derivations (Word Family Members): (Verb) analyze; (adjective) analytical.

The Vocabulary Equity Challenge

Educators serving English learners and economically disadvantaged youths with

vocabulary voids need to simultaneously shore up their receptive vocabulary and build their productive vocabulary toolkit. It is not essential or realistic for students to develop a proficient command of every word that appears within a unit of study. Many topic-focused and technical terms must be understood adequately to grapple with focal-lesson concepts and processes. However, in the grand scheme of linguistic priorities, the fact that a ten-year-old struggling to acquire academic English cannot effectively pronounce or write biome and habitat is less worrisome than the student’s inability to discuss similarities and differences between two species or their environments. Being able to compare and utilize correct sentence structure and vocabulary for this critical academic competency will be required across subject areas and grade levels, not just within this particular unit of study.

To propel youths with Swiss-cheese English proficiency to higher levels of vocabulary knowledge, teachers must establish priorities for more robust instruction and meaningful, supported application. Over the past two decades, mounting research has highlighted the benefits of planned, intentional vocabulary instruction to support literacy and content learning for all students, native English speakers and English learners alike.

According to the National Reading Panel (2000), effective instruction includes opportunities for incidental word learning through wide reading of texts, complemented by intentional instruction of high-priority words aligned with academic success. Increasing reading volume, with a balance of narrative and informational texts, enhances receptive word knowledge (Cunningham and Stanovich, 1998). However, exposure to words through independent reading does not equip students with the productive word knowledge or confidence to hazard applying new terms and phrases on their own. Marzano (2004) asserts that for students with less-developed English language skills, planned, explicit vocabulary instruction has a more pedagogically defensible track record of improving lesson comprehension and communicative competence than indirect or impromptu approaches.

Explicit Vocabulary Instruction to Build Productive Word Knowledge

Explicit, interactive vocabulary instruction has a clear goal of guiding students in gaining ownership of critical new words. The process of building productive word knowledge begins with actively involving students in reading, pronouncing, chorally repeating, and accurately copying a target word (Beck et al., 2002). To grasp a new academic word, students require an efficiently explained meaning framed in accessible language such as a familiar synonym, rather than a rambling and exhaustive formal definition (Stahl, 1999). Students whose first language shares cognates with English benefit from having parallel words called out, such as the Spanish and English cognates comparison/comparacíon from the common Latin root (Calderón, 2007).

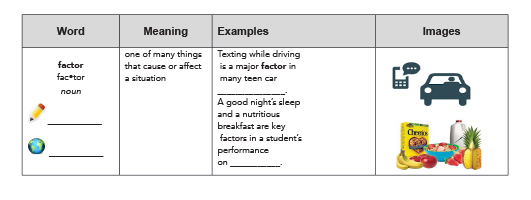

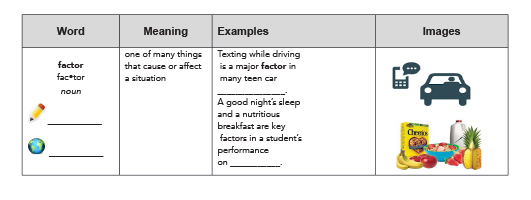

Teacher-generated pictures and simple drawings help students formulate a mental model of the word meaning (Marzano, 2004), but abstract terms such as perspective or bias are difficult to convey in a single, simple illustration. Evocative example sentences can help students create their own vivid and memorable mental images while also helping them understand how the new word functions syntactically and grammatically in an academic statement. When illustrative example sentences strategically include common collocations or word partners, students are more likely to grasp how the word is actually used in academic contexts. Note how the written examples within the notetaking guide in Table 2 include common academic adjectives (major, key) that regularly partner with the high-use noun factor.

The vocabulary notetaking guide in Table 2 includes key elements that should be addressed when developing precise understanding of a high-utility academic word. Without an opportunity to see and pronounce the target word, explore relevant examples, and take some form of notes for review purposes, few learners will recall the meaning. The blanks provide opportunities for students to focus on engaging in repetition and listening comprehension while taking a few critical notes, including correctly copying the word and its cognate (if offered) and completing example sentences provided by the teacher to deepen understanding. The term factor is used widely in discussions of causes and effects in science and social studies lessons as well as news reports. It is a high-value, portable word for text analysis and constructed responses such as informative and argumentative writing. It therefore warrants more time and attention in terms of its formal introduction.

Moving from Basic Understanding to Capable Verbal Application of a Word

The sample vocabulary notetaking guide is a practical tool to present and reliably facilitate recording of essential information about a word. This reference tool effectively guides notetaking and discussion, but it does not ensure productive word knowledge. Neophyte academic-English speakers deserve carefully crafted opportunities to successfully flex their language muscles using a new word. Simply asking provocative questions will not elicit competent use of the word in a complete sentence. Imagine the following common classroom scenario. After introducing the meaning of the lesson term factor, the teacher strives to deepen understanding by asking “What factors do you consider when you pick out a new book to read at the school library?” After a lengthy pause, one fledgling volunteer offers “the pictures,” prompting a classmate to add “the author.” While conceptually on task, neither response demonstrates capable use of the word—that is, productive word knowledge. When encouraged to try to reframe a brief contribution in a complete sentence, the puzzled volunteer replies “It’s the pictures,” failing to comprehend the request for a more thoughtful response in academic register.

Form-focused and carefully scaffolded verbal exchanges equip English learners and reticent readers with the linguistic competence to successfully apply newly taught words (Coleman and Goldenberg, 2012; Dutro and Kinsella, 2010). Interacting with their teacher and peers in structured verbal and writing tasks using response frames enables less-proficient readers and English learners to take careful notice of how the new word operates grammatically. Carefully orchestrated initial practice using a sentence scaffold increases the odds that students develop accurate fluency, the ability to effortlessly produce error-free, contextually appropriate language (Dutro and Kinsella, 2010).

Response frames such as those included in Table 3 also equip the teacher with a concrete mechanism for verbal and written modeling. Simply offering a model verbal response to a lesson question places the burden for auditory processing and analysis on academic English learners. Rarely are they able to hold the modeled response in their short-term memories, deconstruct how it is being utilized, and effectively reconstruct a capable individual contribution. At best, they can recollect some of the content in the response, but not the linguistic elements such as sentence structure and grammatical nuances. If we intend to help them effectively utilize the word on subsequent academic response tasks, we owe it to them to offer more than verbal examples and encouragement.

Table 2: High-Utility Academic Vocabulary Notetaking Guide

Table 3: Sentence Frames for Scaffolded Verbal Tasks

Target High-Utility Academic Word: factor

• Sentence Frame (including the word but requiring appropriate content)

• Not wearing ____________ is often a major factor in

skateboarding injuries.

• The main factor in my decision not to go to the _______________________ was that I had __________________.

• Sentence Frame (requiring the correct word form and appropriate content)

• One of the most important __________________when I pur-

chase a gift for a close friend is the _______________________.

• One major ____________ that can contribute to a

(positive, negative; high, low) ___________ grade on a test is

____________________.

Developing Academic Writing Proficiency with High-Utility Words

For many teachers, the phrase teaching vocabulary conjures up an eclectic array of word sorts, matching exercises, crossword puzzles, concept organizers, and picture drawing. These random activities are typically silent, independent, and unmonitored tasks that might reasonably follow, but not replace, intentional instruction in word meanings and carefully orchestrated applications. Our most vulnerable language learners deserve more support in applying new words than a homework exercise requiring an independently drawn picture and related sentence.

As a long-time educator of striving readers and English learners, I have witnessed first hand the outcomes of their neophyte, ill-supported efforts. My own adopted son, John Carlos, joined our family from Guatemala at nearly four years old. With the Spanish and English proficiency of a toddler entering kindergarten, he struggled in two languages throughout primary and upper-elementary grades. I recall vividly and painfully his weekly earnest attempts to utilize a seemingly random array of words from a literary unit in original

sentences or a paragraph. Every week I resurrected every bit of patience and linguistic acumen I could to help him grasp disconnected words he barely recalled from English language arts lessons.

After helping him develop some basic understanding of a word, our next challenge was applying it in a sentence. When left to his own devices, his default was to write a brief phrase or sentence about our French bulldog, Polo. Polo is immortalized in countless three- to five-word sentences using vocabulary from numerous thematic units, ranging from loyalty and friendship to identity. Invariably, the brief, simple, and often grammatically inaccurate sentences contained no context whatsoever, nor did his recursive default picture of Polo. Table 5 (overpage) includes a couple of classic early writing and artistic efforts from his third-grade experience. My mounting frustration with the dearth of focused, supported academic-language instruction across elementary grade levels prompted me to write curriculum to help fellow educators engage in this crucial endeavor (Kinsella, English 3D, 2016; Kinsella and Hancock, Academic Vocabulary Toolkit, 2016).

I have every confidence that parents like myself of English learners and less-confident readers would welcome homework assignments that provided their children with more clearly scaffolded opportunities to practice new words in speaking and writing. The weekly crossword puzzle and list of words to include in original sentences do little to engender confident parental engagement or academic writing proficiency. Brief sentence-level frames such as those in Table 3 are ideal for initial verbal and written practice.

Writing frames and focused prompts such as those in Table 4 enable the teacher to orchestrate a brief, constructed multiple-sentence response. This scaffolded response can serve as a “we do it” task before students engage in an independent “you do it” comparable task, leveraging the text structure and rhetorical forms included in the preceding guided task. Opportunities for academic English learners to successfully complete brief, supported academic responses build the competencies for longer, independent tasks in ways that unleashed journaling and sentence generation do not.

Table 4: Scaffolded Writing Tasks

Target High-Utility Academic Word: factor

• Read the prompt. Construct a thoughtful response that includes relevant examples.

PROMPT 1: What are key factors a parent must consider before leaving a child at home alone?

Parents must consider several _______ before leaving a child at home alone. One key _______ is the child’s _____________. Another equally important ________________ is how _______ the child is.

• Read the prompt. Construct a three- to four-sentence response with transitions and examples.

PROMPT 2: What are key factors you consider when selecting a book from the school library to read for pleasure?

Table 5: A Third-Grade English Learner’s Independent Word Study

Concluding Remarks

Since word knowledge is such a potent and undisputed predictor of academic achievement, educators across grade levels and content areas cannot afford to leave vocabulary instruction to chance. Our most vulnerable scholars look to us to build their lexical foundations for the collaboration, text analysis, and skillful academic-response demands posed by our nation’s college- and career-readiness focus. With a unified school front to effectively teach critical words and structure competent applications, English learners and their under-resourced classmates can make the linguistic strides that will help them defy the odds and actualize their greatest educational ambitions.

References

August, D., and Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing Literacy in Second Language Learners: Report of the National Literacy Panel on Language-Minority Children and Youth. Center for Applied Linguistics.

Baumann, J., and Kaméenui, E. (2004). Vocabulary Instruction: Research to Practice. Guilford Press.

Beck, I., McKeown, M., and Kucan, L. (2002). Bringing Words to Life: Robust Vocabulary Instruction. New York: Guilford Press.

Biemiller, A. (1999). Language and Reading Success. Brookline Books.

Calderón, M. (2007). Teaching Reading to English Language Learners, Grades 6–12. Corwin Press.

Carlo, M., August, D., and Snow, C. (2005). “Sustained Vocabulary-Learning Strategies for English Language Learners.” In E. H. Hiebert and M. Kamil (eds.), Teaching and Learning Vocabulary: Bringing Research to Practice. 137–153. New York: Wiley.

Chall, J., and Dale, E. (1995). Readability Revisited: The New Dale-Chall Readability Formula. Brookline Books.

Coleman, R., and Goldenberg, C. (Feb. 2012). “The Common Core Challenges for English Language Learners.” Principal Leadership. National Association of Secondary School Principals.

Cunningham, A., and Stanovich, K. (1998, Spring/Summer). “What Reading Does for the Mind.” American Educator, 22(1/2): 8–15.

Dale, E. (1965). “Vocabulary Measurement: Techniques and major findings.” Elementary English 42, 82–88.

Dutro, S., and Kinsella, K. (2010). “English Language Development: Issues and implementation in grades 6–12.” In Improving

Education for English Learners: Research-Based Approaches. California Department of Education.

Flynn, J. R. (2006). Where Have All the Liberals Gone?: Race, Class, and Ideals in America. Cambridge University Press.

Graves, M. F. (2006). The Vocabulary Book: Learning and Instruction. IRA.

Kinsella, K. (2016). English 3D: Course A, B, & C. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

Kinsella, K., and Hancock, T. (2016). Academic Vocabulary Toolkit, Grades 3–8. National Geographic Learning – Cengage.

Marzano, R. (2004). Building Background Knowledge for Academic Achievement: Research on What Works in Schools. ASCD.

Nation, I. S. P. (1990). Teaching and Learning Vocabulary. Newbury House.

National Reading Panel Report. (2000). Teaching Children to Read: An Evidence-Based Assessment of the Scientific Research Literature on Reading and Its Implications for Reading Instruction.

Saville-Troike, M. (1984). “What Really Matters in Second Language Learning for Academic Achievement?” TESOL Quarterly 18: 199–219.

Stahl, S. A. (1999). Vocabulary Development. Cambridge: Brookline.

Kate Kinsella, EdD ([email protected]) is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her numerous publications and programs focus on career and college readiness for academic English learners and under-resourced youths, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading, and writing across subject areas.

The Toronto and York Region Labor Council (TYRLC) has released a series of videos aimed to help Chinese workers with limited proficiency with English confront worker’s rights, labor laws, and other work-related issues. The Toronto and York Region council is based out of Ontario, Canada, and “combines the strength of hundreds of local unions… [and whose] mandate is to organize and advocate on issues that are vital to working people throughout the region.”

The Toronto and York Region Labor Council (TYRLC) has released a series of videos aimed to help Chinese workers with limited proficiency with English confront worker’s rights, labor laws, and other work-related issues. The Toronto and York Region council is based out of Ontario, Canada, and “combines the strength of hundreds of local unions… [and whose] mandate is to organize and advocate on issues that are vital to working people throughout the region.”

Netflix has just released its new Spanish-language series, Ingobernable. Netflix has had its fair share of success recently in the Spanish-language department, most notably the 2015 Spanish-language drama Narcos, a crime drama filmed in Colombia that follows the story of drug kingpin, Pablo Escobar. Narcos was wildly successful with American audiences, and presumably proved to Netflix that English-speaking audiences are open-minded when it comes to content presented in Spanish. The online video service therefore rolled out the carpet again for a release of Ingobernable. The title means ungovernable in English, and is most likely referencing the tumultuous socio-political climate of Mexico that the show encompasses.

Netflix has just released its new Spanish-language series, Ingobernable. Netflix has had its fair share of success recently in the Spanish-language department, most notably the 2015 Spanish-language drama Narcos, a crime drama filmed in Colombia that follows the story of drug kingpin, Pablo Escobar. Narcos was wildly successful with American audiences, and presumably proved to Netflix that English-speaking audiences are open-minded when it comes to content presented in Spanish. The online video service therefore rolled out the carpet again for a release of Ingobernable. The title means ungovernable in English, and is most likely referencing the tumultuous socio-political climate of Mexico that the show encompasses. In this issue:

In this issue: M. Elhess, E. Elturki, and J. Egbert offer strategies to support creativity in the language classroom

M. Elhess, E. Elturki, and J. Egbert offer strategies to support creativity in the language classroom ATi Studios has released a virtual reality app for language education to combine the artificial-intelligence technology behind chatbots with speech recognition in virtual reality. Learn Languages VR by Mondly allows people to experience lifelike conversations with virtual characters, in 28 different languages. The new VR application is intended to realize virtual reality’s promise of rich, immersive, and automated educational experiences. The app offers instant feedback on pronunciation, suggestions that enrich learners’ vocabulary, and surprises that transform learning a language into a fun experience.

ATi Studios has released a virtual reality app for language education to combine the artificial-intelligence technology behind chatbots with speech recognition in virtual reality. Learn Languages VR by Mondly allows people to experience lifelike conversations with virtual characters, in 28 different languages. The new VR application is intended to realize virtual reality’s promise of rich, immersive, and automated educational experiences. The app offers instant feedback on pronunciation, suggestions that enrich learners’ vocabulary, and surprises that transform learning a language into a fun experience.

Drawp for School is a digital content-creation and collaboration tool with embedded language scaffolds for English language learners (ELLs). Teachers use Drawp to provide language-scaffolding support to assignments in any subject. Students can work on those assignments with text, voice, or sketched responses—individually or in groups. Drawp helps teachers generate comprehensible input for students for any assignment, and it encourages language-transfer skills. The language scaffolds were developed by the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE), and the Digital Scaffolding Tool for English Language Learners, Powered by Drawp for School was recently awarded support from the National Science Foundation.

Drawp for School is a digital content-creation and collaboration tool with embedded language scaffolds for English language learners (ELLs). Teachers use Drawp to provide language-scaffolding support to assignments in any subject. Students can work on those assignments with text, voice, or sketched responses—individually or in groups. Drawp helps teachers generate comprehensible input for students for any assignment, and it encourages language-transfer skills. The language scaffolds were developed by the Los Angeles County Office of Education (LACOE), and the Digital Scaffolding Tool for English Language Learners, Powered by Drawp for School was recently awarded support from the National Science Foundation.

Antura and the Letters and Feed the Monster, the two winners of the

Antura and the Letters and Feed the Monster, the two winners of the  Dr. Kate Kinsella offers evidence-based instructional practices to advance students’ verbal and written command of critical words

Dr. Kate Kinsella offers evidence-based instructional practices to advance students’ verbal and written command of critical words