Vista Higher Learning’s Norah Lulich Jones explains how their new Senderos program gets students speaking in class

Vista Higher Learning’s Norah Lulich Jones explains how their new Senderos program gets students speaking in class

First, let us take a look at what students are hoping for, what we are hoping for as teachers, and why speaking in class might not happen as spontaneously as we might have hoped.

Students, even those who have not necessarily signed up for a world language class because of their own intrinsic interest (“My friends are all in this class”), usually say what they hope to get is the ability to speak with young people and make friends. That touches on what we want, too. Being sympathetic and knowledgeable, we use our friendly tone to warn them that they will not be able to speak fluently right away, that they should be ready to take risks and not be perfect, and that we are there to help them so they can make new friends all over the world. Why, then, does all that not get and keep students talking?

While we could spend a lot of time on adolescent psychology, goodness knows, we can sum up both students’ needs and students’ blockages with three words: survival, belonging, and competence. In the hierarchy of needs, these three come in order.

The students in our classes are adolescents who already have a native language; they have survived and do not need this new one to stay alive. So we can encourage, set up an immersive environment, and so forth, but the need to communicate is not linked to survival. Next, adolescents’ brains are wired so they really do feel like they will die if their friends reject them in any way. So, if taking a risk and failing loses them the group they belong to now, our promises of a larger group to belong to in the future provide little comfort. Even if students thread their way through these first two visceral needs, the very nature of learning a new language with an adult brain means they notice they sound like babies (lack of competence).

With these three strikes against adolescents, it is a wonder they speak at all. Yet there is hope, for these young-adult learners will respond to a corresponding trio of gifts we can provide them that will, indeed, get them talking. We can immerse them in motivation for the short term (so they can survive), in purposefulness for the long term (so they belong), and within personalization always (so they are competent). These three aspects are key no matter what instructional programs or resources are being used, and Vista Higher Learning’s Senderos program was specifically designed to address these key aspects in its instructional design, in its content, and in the integrated digital environment which was developed specifically for language acquisition.

Motivation short term for speech comes from a safe environment to explore without judgment, while receiving immediate feedback. It is like providing each individual student a flashlight to illuminate a pathway in the darkness. Motivation is the purpose and design around the student-directed learning approach of our program, both in print and online.

The first step we can take to invite motivation for speaking is to break the broader language topic into comprehensible, manageable language chunks. We tap on students’ successful survival in the world, as it were, by activating their prior knowledge, experiences, and opinions and then connecting each aspect to the material they are about to learn. Students go to their password-protected personal course on VHLCentral.com, where they begin in the Explore activity sequence. Through audio, text, photos, and media in storyboard video-clip format, students figure out where they “fit” in their new language, in a safe environment where they get immediate and private feedback without judgment. Their participation, not their performance level, is key. Just like using the flashlight on the pathway, each student can walk at the pace he or she wants. Comprehensible input is paired with self-pacing. Students feel like they are still in control of their lives: they can relax; they can survive.

Motivation for that short-term, daily support next comes through our shifting and leading students from purely receptive to interactive learning. The powerful Learn activity sequence of the online environment, for example, provides embedded quick checks which give students immediate, personalized feedback as they begin to speak, without grading (and thus demotivating) them. In the important area of vocabulary development, Learn is a cyclical learning sequence that moves from listening and repeating (“How does the word look and sound?”) to matching (“Which photo represents the word?”) to saying it (“Do I know how to recognize the photo and say the word?”). Students develop a sense of hope and confidence as they proceed in (literal) baby steps in learning how to speak, without peer judgment, and spending as much or as little time as needed for personal success.

Next, we lead students toward the deep end of the pool, as it were: actually saying something, but—here is our motivational goal—receiving immediate, appropriate feedback. Notice here that the feedback does not always have to be positive. In fact, students understand that real feedback in small doses, with pathways to improving personal performance quickly, respects them as adult learners. Such feedback is more “real” and more motivating than our well-meaning “Well done!” in any language. In Senderos, such instant and specific feedback is provided by the unique speech-recognition feature embedded in the presentation of vocabulary, pronunciation, and media sections. Developed for Vista Higher Learning by speech-recognition experts in the app world, this feature identifies student utterances, compares them against those of hundreds of native speakers, and provides instant thumbs up/thumbs down feedback. For digitally responsive adolescents, this is a captivating challenge and a game they utterly buy into.

And even though they may not know this, students intuit the reality of their experience with this software: they do not have to sound exactly like the native speaker in order to be judged understood (thumbs up); small things they may not have noticed as they first started learning can make the difference between being understood and not (thumbs down); and small efforts on small tweaks make all the difference (thumbs up). In other words, yet again students learn that they can stay in control and that mistakes can be overcome—and quickly and at low levels of effort.

Let us now combine the frequent motivation sequence we have explored (and which allows students to feel they will survive if they talk) with the longer-term purposefulness aspect (which will ensure students know that they will belong in the world). Purposefulness is more than a periodic bow to “relevance.” It is, as it were, the pathway all lit up, leading a student forward with confidence. Purposefulness comes, in a classroom setting, from instructional design that replicates natural human language development and use in the world. The stages are: (1) life context (personal experience); (2) vocabulary as a tool (target-language building blocks in that familiar context); (3) shared experience (in instructional settings, through media which bridges the language and culture of the student to the target in the same context); (4) target experience in the life context (linguistic and cultural target perspectives and practices in the context); (5) grammar as a tool (gaining communication complexity and accuracy in the context); and (6) synthesis (gaining linguistic and cultural fluency in the context). These inherent human steps focus students’ attention on meaning and community, versus personal performance, and help them feel they belong.

We have gotten students to know they can speak. How do we keep them speaking? How do we ensure they keep on talking? We make sure that, throughout all the contexts in the instructional design where they are talking about contexts in which they have experiences, being asked about their reactions to things they see and hear, are comparing their lives (products, practices, and perspectives) to those of their target peers and doing activities that use vocabulary and grammar as tools to talk about their own situations. That is, as much as possible, every activity is personalized. Students know themselves best and apply their daily practice and longer view to their own real interests. Confidence building is a feedback loop of its own. Again, in this matter, Senderos focuses on this truth of human psychology and learning, carefully constructing scaffolded activities that personalize each context and experience.

We are almost done in our consideration of how to get students to speak. But there is one more element: you, the teacher. You are motivated as you see students engaged daily. You see purposefulness as you achieve your course objectives. And, using good tools and good approaches, you are able to integrate your objectives into your style and your personal dreams, making your work easier and more effective. That is also a key goal and purpose of Senderos, both in its student content and in the teacher resources, course setup templates, and digital planning, teaching, and assessing tools.

That is how you get and keep students talking—for life.

Norah Lulich Jones, MEd, is professional development liaison for Vista Higher Learning (VHL). She has been a teacher for multiple decades of Spanish, French, and Russian in public and private schools, a member of and trainer for NADSFL, a keynoter and workshop presenter for conferences and school districts, and a writer of student and teacher materials for VHL and (historically) several other publishing companies.

A new report released by Californians Together shows that many school districts across the state are currently facing a growing bilingual teacher shortage, and that in the near term, there is a pool of at least 7,000 bilingual teachers who are well positioned to begin to address this shortage, and need to be supported with professional development.

A new report released by Californians Together shows that many school districts across the state are currently facing a growing bilingual teacher shortage, and that in the near term, there is a pool of at least 7,000 bilingual teachers who are well positioned to begin to address this shortage, and need to be supported with professional development.

The Welsh government has announced a new, ambitious plan to almost double the amount of Welsh speakers in the country. The declaration follows the 2011 census, which showed a drop in the number of speakers in Wales from 21.7 percent to 19 percent of the population, or 562,000. The government also seeks to increase the percentage of the population that speaks Welsh daily, and can speak more than just a few words from 10 percent to 20 percent. The goal’s deadline is 2020, and Welsh government aims to accomplish it through a three-step

The Welsh government has announced a new, ambitious plan to almost double the amount of Welsh speakers in the country. The declaration follows the 2011 census, which showed a drop in the number of speakers in Wales from 21.7 percent to 19 percent of the population, or 562,000. The government also seeks to increase the percentage of the population that speaks Welsh daily, and can speak more than just a few words from 10 percent to 20 percent. The goal’s deadline is 2020, and Welsh government aims to accomplish it through a three-step  The Institute of International Education (IIE) has announced a new survey on international admissions, and the conclusions are more optimistic than some may have expected.

The Institute of International Education (IIE) has announced a new survey on international admissions, and the conclusions are more optimistic than some may have expected.

Sara Quintanar, an elementary school music educator, bilingual songwriter, and performance artist, has taken the international community by storm with her songs in Spanish for English-speakers to learn the language.

Sara Quintanar, an elementary school music educator, bilingual songwriter, and performance artist, has taken the international community by storm with her songs in Spanish for English-speakers to learn the language. Vista Higher Learning’s Norah Lulich Jones explains how their new Senderos program gets students speaking in class

Vista Higher Learning’s Norah Lulich Jones explains how their new Senderos program gets students speaking in class

A new study has found that patterns exist within the visual structure of sign language. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (

A new study has found that patterns exist within the visual structure of sign language. The study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America ( Languages Canada and the Ministry of Education of the Mexican State of Guanajuato have signed a cooperation agreement to formalize and expand collaboration in English and French language education.

Languages Canada and the Ministry of Education of the Mexican State of Guanajuato have signed a cooperation agreement to formalize and expand collaboration in English and French language education. sponsible for administering programming and funding on behalf of the Ministry of Education. “[To] educate is to transform people. [To] educate is to have a better society. Education is necessary and vital to the construction of a learning society; it simply cannot develop itself without knowledge,” said Vega Pérez.

sponsible for administering programming and funding on behalf of the Ministry of Education. “[To] educate is to transform people. [To] educate is to have a better society. Education is necessary and vital to the construction of a learning society; it simply cannot develop itself without knowledge,” said Vega Pérez.

The senate is considering updating the criteria for reclassification for English Language Learners (ELL’s) in the state of California with Senate bill

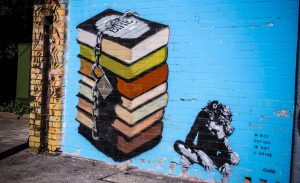

The senate is considering updating the criteria for reclassification for English Language Learners (ELL’s) in the state of California with Senate bill  Changing the World, One Wall at a Time

Changing the World, One Wall at a Time The Bahá’ís, Iran’s largest religious minority, are denied access to higher education. There are 74 Bahá’ís currently imprisoned, and more than 200 were executed in the early 1980s after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Thousands of Bahá’ís are currently studying through an underground education system known as the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE). Not a Crime is working to stop the human rights abuse of young people barred from studying because of their beliefs and is encouraging universities worldwide to admit Iranian Bahá’í students. The education campaign started in 2015 with an Education Is Not a Crime Day (the last Friday of February 2015) and screenings of a film Bahari made called To Light a Candle—and now it has grown into a movement. Mark Ruffalo of The Avengers, Rainn Wilson of The Office, Desmond Tutu, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and rights activist, and Shirin Ebadi, also a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, have spoken against the persecution of the Bahá’ís. Nearly 100 universities—including Stanford and Yale—currently accept the BIHE certificate.

The Bahá’ís, Iran’s largest religious minority, are denied access to higher education. There are 74 Bahá’ís currently imprisoned, and more than 200 were executed in the early 1980s after the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Thousands of Bahá’ís are currently studying through an underground education system known as the Bahá’í Institute for Higher Education (BIHE). Not a Crime is working to stop the human rights abuse of young people barred from studying because of their beliefs and is encouraging universities worldwide to admit Iranian Bahá’í students. The education campaign started in 2015 with an Education Is Not a Crime Day (the last Friday of February 2015) and screenings of a film Bahari made called To Light a Candle—and now it has grown into a movement. Mark Ruffalo of The Avengers, Rainn Wilson of The Office, Desmond Tutu, the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and rights activist, and Shirin Ebadi, also a Nobel Peace Prize laureate, have spoken against the persecution of the Bahá’ís. Nearly 100 universities—including Stanford and Yale—currently accept the BIHE certificate. Forty-one murals have been painted in U.S. and international cities as part of the project—Atlanta, Cape Town, Delhi, London, Nashville, Sao Paulo, Sydney, and two dozen in New York City. Nineteen of the New York murals were painted in the iconic Harlem neighborhood because of its long association with cultural innovation during the Harlem Renaissance and the 1960s civil rights movement.

Forty-one murals have been painted in U.S. and international cities as part of the project—Atlanta, Cape Town, Delhi, London, Nashville, Sao Paulo, Sydney, and two dozen in New York City. Nineteen of the New York murals were painted in the iconic Harlem neighborhood because of its long association with cultural innovation during the Harlem Renaissance and the 1960s civil rights movement.