|

Sara Davila uses theory and research to hit the learning sweet spot

Sara Davila uses theory and research to hit the learning sweet spot

You walk into your classroom ready with a full selection of lesson plans for the week, excited to deliver some compelling learning to your students. You’ve worked hard to put together a lesson you feel is both challenging and engaging, with language that will be relevant and meaningful to your learners. Everything is running along beautifully until you actually start your lesson. That sinking feeling is the realization that:

the students already know the language;

they are going to finish most of the work within the next five minutes;

you are going to need to fill about 30 minutes of class time.

I have certainly had this experience, and many teachers have had something similar. I have also had the opposite experience of preparing content I thought would be appropriate only to find out it was too challenging. By the time I had my students prepared, there was no time left for any communicative activity or anything that might go beyond surface-level language function. So, how do we get to what can be described as the “Goldilocks lesson”—the one that is not too hard, not too easy, but just right? For this, some practical tools and  a little learning theory can help to better reach the sweet spot of learning.

a little learning theory can help to better reach the sweet spot of learning.

The Zone

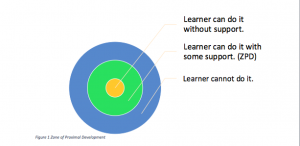

What can we do to target just the right spot for learning in our lessons? To try to answer this question, we are going to look at some very practical learning theory that you may or may not be familiar with. In his work on learning and education, Vygotsky introduced the concept of the zone of proximal development for learning (Vygotsky, 1978).

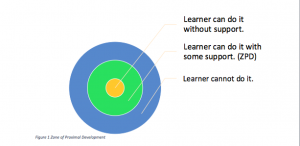

In summary, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the space between where a learner can do something with complete independence and the point where the learner cannot do it at all, even with assistance or intervention from the teacher. The ZPD is that point where the learner can do something, but only with support and assistance from the teacher. This support is often described as scaffolding. ZPD and scaffolding go hand in hand as a way in which to help our learners achieve.

In summary, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the space between where a learner can do something with complete independence and the point where the learner cannot do it at all, even with assistance or intervention from the teacher. The ZPD is that point where the learner can do something, but only with support and assistance from the teacher. This support is often described as scaffolding. ZPD and scaffolding go hand in hand as a way in which to help our learners achieve.

Using ZPD alongside i(input)+1

In language, we want to identify what learners can do, can do with assistance, and simply cannot do. How do we get to that point, and what can we use to determine an appropriate zone of learning? The answer to this question has many similarities to an idea which many language professionals will already be familiar with: Krashen’s i+1 theory (1981).

Introduced as communicative language theory, it began to gain prominence in language teaching. “i+1” describes a specific task in language lessons that is just above the current level of the student’s understanding and is introduced as a way to provide a challenge, in order to keep the student engaged and motivated.

Like ZPD, i+1 highlights that we need to be targeted in our approach to learning and use this additional insight into the progress the student is making, whether it is self-motivated or with support from the teacher. However, it can be challenging to identify where exactly the challenge or zone will be. As I described at the beginning, we do not want to discover our lesson plan is either far too easy or far too difficult.

So, how can we define the zone in our classroom, assess our curriculum and support materials, and develop content that will target that optimal area for learning?

Scales and the Learning Sweet Spot

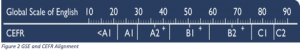

The best way to understand where to focus is to have a good sense of where our students are in the learning journey. One of the most widely recognized and used tools to describe that point is the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages or CEFR (Council of Europe, 2001).

The CEFR provides us with a common vocabulary which we can use to describe learner performance. I find that using CEFR levels is a practical and handy shortcut to ground my expectations of what learners can do. The variety of “can do” descriptors originally developed also creates a formative roadmap, useful for understanding what learners need to master in order to continue to make progress.

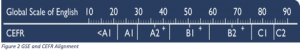

There are challenges with using the CEFR alone, the two biggest being the distribution of descriptors across the skills and the lack of granularity. This is where the Global Scale of English (GSE) provides a helping hand. The GSE is an 80-point scale aligned to the CEFR which allows educators to more closely describe precisely where learners are in their learning journeys.

The GSE expands on the initial research conducted by the Council of Europe, developing “can do” statements which are leveled and aligned to the CEFR scale (de Jong, Mayor, and Hayes, 2016). Over the past two years, over 1,000 descriptors have been added to expand and provide more detailed insight into the CEFR.

In the last twelve months, as I worked with the GSE, I began to realize that the granularity inherent in the GSE could provide a real window into target ZPD in the classroom to drive learner performance and progress. If I have a baseline level of where I expect my learners to be, by using the GSE, I can focus on specific areas that will help push progress during the time I have available to work with them. Where the CEFR provides a broad description of what I can expect from my students, the GSE provides a more detailed view of the learning journey and enables me to look in a more granular way at specific techniques to help drive progress. However, like with any good tool, some skill and practice are required to get the best results.

The GSE and the Learning Journey

The GSE and the Learning Journey

The GSE provides reference points we can use in our classrooms to help target a zone of learning, especially if we take into consideration what it means for a student to be “at” a level in the GSE.

The definition proposed here and elsewhere (see for example Adams and Wu, 2002; de Jong, Bernstein, and North, 2001; de Jong, 2004) is the following: being at a CEFR level is defined as having at least a 50% probability of being able to perform all language activities at that given level of proficiency.

If this proficiency level is defined as an interval on a scale, e.g., B1 on the CEFR, being at B1 means a learner is expected to be able to perform at least 50% of all tasks at B1 or to have a 50% chance of being able to perform any task at B1. As a learner advances within a level, this probability increases. Given the width of the CEFR levels, when a learner reaches about 80% within a level, the learner is likely to be entering the next level, again with a 50% probability of successfully performing any language task at that next level. If proficiency is defined as a point on a scale, e.g., 61 on the GSE, then a learner is expected to be able to perform 50% of all tasks which are at 61 on the GSE or to have a 50% chance of being able to perform any task at 61 on the GSE.

In other words, to say that a learner is at a certain level on the Global Scale of English does not mean she has necessarily mastered every GSE learning objective for every skill up to that point. Neither does it mean that she has mastered none at a higher level. She has a 50% likelihood of being capable of performing learning objectives at that level—and a greater probability of being able to perform learning objectives at a lower GSE level. As proficiency increases, the probability of being able to perform the learning objectives at the given level (in this case, 61) also increases (see Figure 3) (de Jong, Mayor, and Hayes, 2016).

The GSE gives us an understanding of what learners can probably do, and having this information in the classroom allows educators to think and plan carefully about how to target skills inside a zone that will drive learner progress.

Selecting a Zone

Selecting a Zone

Now that we have all this detail about student performance, how do we target the sweet spot, or the zone of proximal development? There are a few considerations educators will need to explore to get to the best zone for learning, including expected range of performance, our overall expectations of learning progress, and the number of hours of input in a course (Benigno, de Jong, and Moere, 2017). These three areas can help us to plan a zone that will be appropriate and achievable for our students. This is where the “skillful educator” takes over to help shape and craft a plan.

Here is an example of an educator thinking through these three variables to determine an appropriate ZPD to target during a course.

Range of Performance

I know, based on my learners’ test scores, observable assessment, and my teacher evaluation, that students are working at a B1 level. Their B1 performance is between 43 and 50 on the GSE. My learners consistently perform well with skills between 43 and 46 and need scaffolding to accomplish skills between 47 and 50. I define the general range of performance as 44–48.

Desired Learning Outcomes

During the course, the goal is to help learners make progress in the B1 level. Ideally, by the end of the course, learners will be able to work well with B1+ level skills. The desired GSE range is to have students working consistently with skills 51–55.

Hours of Input

The intensive six-week program requires a total of 110 classroom hours and an additional 30 hours, which include homework, field trips, and lab work, for a total of 140 hours of learning input.

ZPD

Content from 51–57 will need additional scaffolding. This content will also challenge students the most to drive learning. This content is in the zone.

This same thinking can be applied to your own learning programs and classrooms. Once a target zone has been established, the learning objectives provided through the GSE, aligned to the CEFR, can help to target specific skills of learning. Ideally, we want to select learning objectives that are in the zone and also align closely with the stated learning outcomes for the program. In this way, we can best target our learning to create the most progress while still meeting our stated program outcomes.

Balancing the Zone

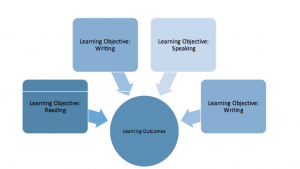

How many learning outcomes and learning objectives do you need to cover in a course? To answer this question, it helps to break down the difference between the two. Learning outcomes should describe the cumulative learning of a course. There will be fewer learning outcomes, since these are the big-picture goals. Learning objectives are the day-to-day goals. These are the observable objectives that will be incorporated into a lesson plan. A course may have a large number of learning objectives that align to the expected end-of-course learning outcomes (Diamond, 1998).

So, how many do you need? That will depend on a few key factors: length of course, course expectations, and assessment. For a typical eight-week course, I would expect to see between 25 and 30 learning outcomes. The total number of objectives will likely be higher, with each objective aligned to the expectations of the course. This is a starting point for thinking about how to plan my course to facilitate a solid learning zone.

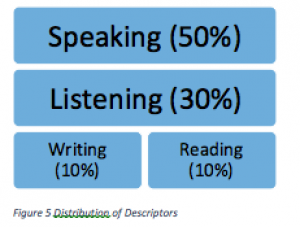

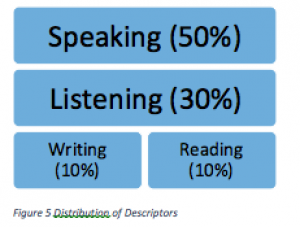

The next thing to think about is how the learning outcomes are distributed across the skills in the course. To understand this, we need to think about the focus of the course: skills, blended skills, academic skills, or something else? For example, this semester I may have a general conversation course focused on speaking and listening for my B1 students

As the program designer, I want to be sure that I have a good representation of speaking skills in the zone. I am also aware that this course will include some listening, reading, and writing focus to support my students and help drive their progress. This helps me understand how I need to distribute the descriptors in my course: heavy on speaking, balanced against listening, with less reading and writing.

Now that I have an idea of the distribution, looking at the progress I want to make, I can target the zone. Thinking about where I expect my students to start (lower B1) and where I want my students to finish (closer to B1+ if not solid B1+), I can form a plan of attack. In my thinking on how to select descriptors, I decide to have a small number at the expected level of student ability, a solid number slightly above or far above, and at least one or two descriptors that will be stretch goals. Knowing the distribution, I can anticipate that by the end of the course, most of the students should be able to demonstrate the lower descriptors and the mid to high, and a few students may have achieved mastery with stretch goals, achieving my goal of making progress in their conversation skills by the end of the eight-week course.

Now that I have done the hard part of deciding how and where to divide my learning objectives, I can dive into the Global Scale of English and start to attribute learning objectives that will reflect my desired learning outcomes. As there are over 1,500 learning objectives, this may take a bit longer, but at least I know how many I will need to find to further develop my course to guarantee expected achievement.

In this example, I am working independently; however, once a basic understanding of the number of outcomes, distribution, and zone ofdevelopment has been established, an institution could decide to have a more formalized process of selecting descriptors by working in teams, pairs, or other cohorts. The process would really depend on the best ways of working and program development at the individual institution.

Conclusions

It is important to remember that using the ZPD in planning will not allow for 100% coverage of all skills in a range, but it can help us to zero in on skills that will be the most useful to create a challenge and help drive progress in the classroom. This can be especially helpful for moving our students along as they begin to experience the learning plateau. Additionally, while I have examples here, there is no magic wand that will help you decide the number of descriptors needed, learning range, distribution, and zone of development. Think about the needs of your institution or your class and use that information to plan accordingly when developing your course or syllabus.

The beauty, and the benefit, of using the Global Scale of English Learning Objectives aligned to the CEFR is the power that we have, as educators, when looking at how we want to drive learning in our classrooms. We have all experienced that moment when we have created the “sweet spot” for learning. It is what keeps us motivated, right? In my experience, the GSE helps us to hit that sweet spot again and again—resulting in motivated teachers, motivated learners, and, most importantly, the creation of a classroom in which learning is taking place.

References

Benigno, V., de Jong, J., and Moere, A. V. (2017). How Long Does It Take to Learn a Language? Insights from Research on Language Learning. London, UK: Pearson.

Diamond, R. (1998). “Clarifying Instructional Goals and Objectives.” In Designing and Assessing Courses and Curricula: A Practical Guide (Revised ed.). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Jong, J., Mayor, M., and Hayes, C. (2016). Developing Global Scale of English Learning Objectives Aligned to the Common European Framework. London: Pearson. Retrieved from https://prodengcom.s3.amazonaws.com/GSE-WhitePaper-Developing-LOs.pdf.

Krashen, S. (1981). Second Language Acquisition and Learning. Pergamon Press, Inc.

Mayor, M. (2016). “What Does It Mean to Be at a Level in English?” Pearson Blog. https://www.english.com/blog/be-at-a-level-in-english.

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Sara Davila is a teacher, materials writer, researcher, and teacher trainer who has worked in a variety of contexts. She is a learning expert at Pearson Education, a World Learning SIT/TESOL trainer, and an English language specialist at the U.S. Department of State, and she continues to find time to post free materials on her website, saradavila.com.

Kids Discover is releasing 25 new Social Studies titles in time for the new school year. Ten of the new titles have been created for grades K–3, and focus on topics like Rules and Laws, People and the Environment, and U.S. Geography. The remaining 15 titles are a mix of American History and World History titles aimed at upper elementary and middle school learners, with titles like “Westward Expansion,” and “China’s Empires.” These 15 titles will also be released digitally on Kids Discover Online, with assessment questions and interactive features. The online curriculum is now compatible with Google Classroom, including the option for single sign-on.

Kids Discover is releasing 25 new Social Studies titles in time for the new school year. Ten of the new titles have been created for grades K–3, and focus on topics like Rules and Laws, People and the Environment, and U.S. Geography. The remaining 15 titles are a mix of American History and World History titles aimed at upper elementary and middle school learners, with titles like “Westward Expansion,” and “China’s Empires.” These 15 titles will also be released digitally on Kids Discover Online, with assessment questions and interactive features. The online curriculum is now compatible with Google Classroom, including the option for single sign-on.

For many students, having a personal tutor to help them learn new languages, while a fantastic opportunity, may seem out of reach due to financial, geographical, or a myriad of other difficulties. Star Tutors falls in line with the current trend of virtual education and virtual teaching, and aims to make tutoring more accessible to students. Students can access their app on personal devices and their laptop computers.

For many students, having a personal tutor to help them learn new languages, while a fantastic opportunity, may seem out of reach due to financial, geographical, or a myriad of other difficulties. Star Tutors falls in line with the current trend of virtual education and virtual teaching, and aims to make tutoring more accessible to students. Students can access their app on personal devices and their laptop computers.

Sara Davila uses theory and research to hit the learning sweet spot

Sara Davila uses theory and research to hit the learning sweet spot a little learning theory can help to better reach the sweet spot of learning.

a little learning theory can help to better reach the sweet spot of learning. In summary, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the space between where a learner can do something with complete independence and the point where the learner cannot do it at all, even with assistance or intervention from the teacher. The ZPD is that point where the learner can do something, but only with support and assistance from the teacher. This support is often described as scaffolding. ZPD and scaffolding go hand in hand as a way in which to help our learners achieve.

In summary, the zone of proximal development (ZPD) is the space between where a learner can do something with complete independence and the point where the learner cannot do it at all, even with assistance or intervention from the teacher. The ZPD is that point where the learner can do something, but only with support and assistance from the teacher. This support is often described as scaffolding. ZPD and scaffolding go hand in hand as a way in which to help our learners achieve. The GSE and the Learning Journey

The GSE and the Learning Journey Selecting a Zone

Selecting a Zone  Despite being threatened with

Despite being threatened with

Not all linguists make great teachers, so a career in translating or interpreting may be the right move, especially since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 42% increase in

Not all linguists make great teachers, so a career in translating or interpreting may be the right move, especially since the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics projects a 42% increase in Kristal Bivona examines an approach to overcome the inherent imperialism of European language education

Kristal Bivona examines an approach to overcome the inherent imperialism of European language education Kathy Stein-Smith asks what the real story is on the French/English language dynamic in the EU

Kathy Stein-Smith asks what the real story is on the French/English language dynamic in the EU

A new study by University of Washington Institute of Learning and Brain Sciences (I-LABS) researchers, published in Mind, Brain, and Education, investigates how babies can learn a second language outside of monolingual homes. “As researchers studying early language development, we often hear from parents who are eager to provide their children with an opportunity to learn another language but can’t afford a nanny from a foreign country and don’t speak a foreign language themselves,” said Naja Ferjan Ramirez, a research scientist at I-LABS. The researchers developed a play-based, intensive English-language method and curriculum and implemented it in four public infant-education centers in Madrid, Spain, where the country’s public education system enabled the researchers to enroll 280 infants and children from families of varying income levels.

A new study by University of Washington Institute of Learning and Brain Sciences (I-LABS) researchers, published in Mind, Brain, and Education, investigates how babies can learn a second language outside of monolingual homes. “As researchers studying early language development, we often hear from parents who are eager to provide their children with an opportunity to learn another language but can’t afford a nanny from a foreign country and don’t speak a foreign language themselves,” said Naja Ferjan Ramirez, a research scientist at I-LABS. The researchers developed a play-based, intensive English-language method and curriculum and implemented it in four public infant-education centers in Madrid, Spain, where the country’s public education system enabled the researchers to enroll 280 infants and children from families of varying income levels.