Kate Kinsella recommends launching an Academic Language Campaign to prepare diverse learners for the Common Core State Standards

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS, 2010) rolling out in 46 states aim to graduate all U.S. high school students with 21st century communication and literacy skills, career and college ready. These new national standards signal a pronounced shift in how academic language and literacy instruction must be approached. Four particular competencies are emphasized that represent decidedly new expectations for communication, reading, and writing development: 1) engaging with complex texts, with increased percentage of informational material; 2) conducting research and using evidence from diverse sources to construct verbal and written arguments; 3) participating in collaborative academic discussions and presentations; 4) and developing the advanced language proficiency to accomplish all of the above tasks. In grades K-5, the standards detail competencies for students in the areas of speaking and listening, reading, and writing that apply to all elementary subject areas. In grades 6-12, the standards are divided into two major categories: those specifically addressing English language arts and those intended for history/social studies, science, and technical subjects.

The new standards accentuate that career and college readiness entails approaching text with “an appreciation of the norms and conventions of each discipline” (CCSS, p. 60) and writing with understanding of distinct tasks, goals, and audiences (CCSS, p. 63). This shared responsibility for communication and literacy mentoring presents novel opportunities and challenges for educators across the K-12 curriculum. Throughout the school day, students will rely on each and every teacher to adeptly articulate, demonstrate, and coach the foundational language and literacy skills of their discipline.

All Students are Academic English Learners

Teachers serving students from diverse linguistic, social, and economic backgrounds will be particularly challenged to help every learner meet the language demands of rigorous CCSS performance-based assessments, including constructed written responses and formal presentations. When students are already grappling to demonstrate mastery of 20th century academic communication and foundational literacy skills, the prospect of preparing them for 21st century career and college readiness can appear to be a Herculean if not Sisyphean task. English learners and community dialect speakers will indeed require a more informed and concerted school-wide initiative to develop the verbal skills of synthesis, interpretation, explanation, and persuasion they can leverage in academic interaction, reading, and writing. Oral language proficiency underscores advanced academic literacy (August & Shanahan, 2006); Language-minority youths understandably struggle to read and write what they cannot articulate verbally.

With the prospective CCSS assessments 2014 start date looming, school districts across the nation are making initial strides to gear up staff and students alike. Widespread faculty preparations include conducting a standards gap analysis, revisiting Bloom’s Taxonomy, writing depth of knowledge questions, and wedging in informational texts to augment an outdated literature-centric English language arts curriculum. While these curricular-focused preoccupations may serve to introduce more conceptual and textual rigor into conventional lessons, ramping up the level of text and task complexity alone will not ensure positive outcomes for learners lacking academic language proficiency. The CCSS speaking and listening standards call upon students to listen critically and participate in cooperative tasks within all core content classrooms. They must articulate their text comprehension, summarize, make inferences, and justify claims using complex sentences, precise vocabulary, and grammatical accuracy. From kindergarten to high school graduation, English learners and under-resourced classmates will require successful experiences engaging in structured, accountable academic interaction across the school day to meet these performance expectations.

They must also be exposed to an articulate command of English in every class and benefit from consistent school-wide academic language instructional principles and practices.

Ensuring that every student is well equipped with the linguistic resources to tackle grade-level curriculum and assessments in the Common Core era is admittedly daunting. The language of school encompasses “words, grammar, and organizational strategies used to describe complex ideas, higher-order thinking processes, and abstract concepts” (Zwiers, 2008). Academic language proficiency is widely recognized as a pivotal factor in the school success of English learners, and it has been increasingly cited as a major contributor to achievement gaps between language- minority students and English proficient students (Francis, Rivera, Lesaux, Kieffer, & Rivera, 2006). Students who use dialects or regional varieties of the English language that differ strikingly from the language of school are similarly disadvantaged from the outset (Craig & Washington, 2004). Every child is AELL, an academic English language learner, including those from a home in which language usage maps more readily onto classroom contexts. However, youths with limited English proficiency, primary language delays, or nonstandard dialects will arguably have more acute and compelling academic oral language priorities as schools embark upon career and college readiness coursework.

Teaching Academic English by Example

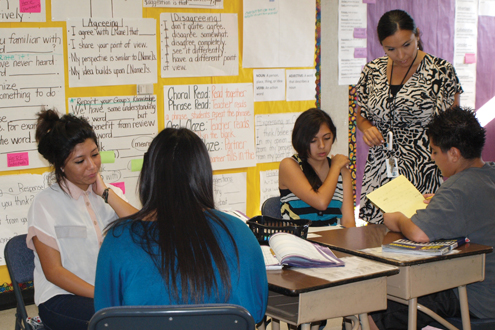

One concrete and manageable way to begin addressing student language needs is to launch a school-wide academic English register campaign. Instead of focusing immediately on faculty discussions of students’ linguistic deficits or attributes, we can turn our attention to teachers’ and administrators’ adept and consistent modeling of academic English language. When classes are comprised of students with differential exposure to advanced English vocabulary and sentence structures, it becomes all the more vital for teachers to serve as proficient and unswerving academic language models. In many schools, English learners and less proficient readers are surrounded by classmates equally challenged by academic language norms and conventions. For these students, the only reliable context for rich and varied exposure to spoken English is the classroom. Teachers can facilitate advanced English acquisition by serving as eloquent and articulate users of both academic and social language. Using complete sentences, precise vocabulary, and a more formal register during lessons will model appropriate classroom language and create a supportive climate for second-language production and experimentation.

In my role as a school consultant and instructional coach on English language development in numerous states, I have become acutely aware of the countless register shifts students experience throughout the course of a school day. Many teachers segue routinely from academic language use to casual vernacular, making it taxing for neophyte academic English speakers to get a handle on school-based language forms. As an illustration of instructional code-switching, consider the linguistic impact when a teacher sets up a collaborative task in this manner: “OK, you guys. I need you to get in your groups right now and make sure you’ve got all your stuff out so you don’t need to go back and get things later and bother anyone. Alright kids, let’s look at your job. I need everyone to read the directions with me: Identify the most convincing evidence provided by the author to support his claim that cyberbullying is not adequately controlled on high school campuses.” Referencing students informally as “you guys” and “kids” cues informality as does use of imprecise terms like “stuff, “things, “bother” and “job.” Transitioning from processing verbal directions posed in familiar social register to digesting written directions and texts framed in sophisticated academic register is tantamount to a linguistic whiplash.

Chronic instructional code-switching serves as a confounding linguistic model; It also inadvertently prompts more informal student language use. When we address students during lessons using a familiar register, we tend to relax our physical stance and communicate nonverbally that we are interacting casually, triggering a reciprocal informal student response. Nonverbal cues often accompany informal instructional register, such as approaching a single student within a lesson and speaking tête-á-tête (one-on-one) or sitting on a table with crossed legs while inviting additional contributions from the unified class.

Launching an Academic Register Campaign

As purveyors of the language of school, teachers across the K-12 spectrum must assume responsibility for exposing their learners to the most articulate and imitable variety of English that will advance their command of academic register. Serving as a viable academic language mentor begins with comprehending and successfully communicating the meaning of register. A register is “the constellation of lexical (vocabulary) and grammatical features that characterizes particular uses of language (Schleppegrell, 2001). In layman’s terms, a register is the word choices, sentence types, and grammar used by speakers and writers in a particular context or for a particular type of presentation or writing. In student-friendly terms, a register is the way we use words and sentences to speak and write in different situations or for different reasons.

Introducing the term register to K-12 students at any age with accessible examples helps to concretize a potentially alien concept. This digitally-savvy generation of secondary school students fairly readily grasps the differences between the language one hastily scribes to send a text message to a friend or family member (abbreviated quotidian words and phrases, incomplete sentences, emoticons) and the more formal tone, complete sentences, and precise vocabulary one deploys in an e-mail message to a strict teacher attempting to communicate a viable excuse for turning in a late high-stakes assignment. Elementary school students easily comprehend the distinctions in the ways we would ask a grandparent, minister, or principal for assistance as opposed to how we might ask a sibling or close friend. Young language scholars in every grade tend to immediately relate to analogies with formal and casual clothing choices. They recognize the inappropriateness of appearing at a family wedding, church service, or formal dance attired in clothing more suitable for weekend chores or playing outside after school with neighborhood friends.

Discussions of register with students should be at once direct, nonjudgmental, and respectful. At no point should an educator ever imply that home use of language is anything less than appropriate. In fact, the term “home language” is best left out of this candid conversation altogether. Students need to rest assured that having an agile command of “everyday English” is absolutely imperative if they wish to have friends and intimate relationships. It is the rare individual who prefers to interact regularly with someone who only utilizes formal academic English. Further, “everyday English” varies from one community to another and moving fluidly within home and school environments warrants being sensitive to language uses in different contexts. Clarifying register distinctions with developmentally-appropriate contrasting terms helps learners at successive language proficiency and age levels continue to grapple with this essential linguistic concept (See Table 1).

Eliciting Academic Responses from Students

After introducing the notion of register, an academic language mentor should clarify for students the essentials of constructing an appropriate academic response. My experiences teaching first generation college freshmen and adolescent English learners have made me keenly aware of the fact that most have progressed in their schooling perplexed by a teacher’s admonition to “respond in a complete sentence.” Consider this commonplace scenario. A social studies teacher poses a discussion question to activate and build background knowledge prior to assigning a chapter on recent U.S. immigration: What are common challenges faced by recent U.S. immigrants? After allowing adequate wait time for individual reflection, the teacher asks a mixed-ability class comprised of native English speakers and English learners “Would anyone like to share?” When no one immediately steps up to the plate to offer a voluntary contribution, the teacher calls on students randomly. Typical responses include “English,” ”New foods,” and “Finding a job.” Probed to rephrase an example in a complete sentence, a flummoxed contributor replies inaudibly “It’s learning English.”

Despite our earnest efforts to elicit detailed and audible responses, few under-prepared students have figured out what we actually mean by “answer in a complete sentence.” What teachers across disciplines anticipate is a complex statement incorporating precise vocabulary from the assigned question, for example, “One common challenge faced by many recent immigrants is learning an entirely different language.” On the first day of my English language development classes, I demystify this process for students while establishing my expectations for active, responsible participation in unified-class and collaborative discussions. I visibly display questions and appropriate complete responses as illustrated in Table 2. The inevitable question arises: “Why didn’t my teachers show me how to do this years ago?” We simply can’t expect language-minority students to be armchair applied linguists successfully deconstructing the nuances of school-based language.

Using Appropriate Terms to Address Students and Teachers

Another practical way to increase the level of language formality in daily classroom interactions is to monitor the ways in which we refer to students throughout a lesson. While coaching English language development teachers in upper-elementary and secondary classrooms, I have observed students immediately sit up and assume a professional demeanor when addressed as young “scholars” or “collaborators,” and revert to a relaxed, disengaged posture when called to attention as “kids” or “you guys.” I make a concerted effort to address my English language apprentices in varied ways depending on the nature of our task. If I am guiding them in writing a brief constructed response, I address them as “co-authors”. If we are analyzing data or evidence-based text, I refer to them as “investigators” or “scientists.” I also make a point to clarify for students the meanings of the terms I am using (See Table 3) and my rationale before encouraging them to demonstrate respect to fellow classmates by following my model and adopting these precise labels for academic and professional peers.

Similarly, students from all backgrounds benefit from learning how to properly address teachers, administrators, and other district employees throughout the school day. An essential component of career and college readiness is recognizing how to address superiors with the appropriate level of formality according to cultural norms. Because I regularly coach instructors on academic English instruction and provide demonstration lessons, language-minority students are often baffled by the proper way to address me. They are apt to hear the principal saying Professor Kinsella, their teacher calling me Dr. Kinsella, and a videographer getting my attention simply using my first name Kate. After spending five days recently teaching adolescent English learners for an instructional DVD, the students ended the week endearingly but inappropriately addressing me as Professor Doctor Ms. Kate Kinsella after I had affectionately admonished a naïve devotee on day three for entering the classroom with the school superintendent present and greeting me with “What’s up, Doc?” I had advised them that it is always prudent to err on the side of formality rather than to address an employer, school administrator, or college professor by their first name.

Utilizing Precise Academic Vocabulary throughout Lessons

An equally significant way to ramp up the register in daily instruction is to make mindful, meaningful word choices when assigning verbal directions or eliciting verbal contributions throughout a lesson. As language role models, we are frequently guilty of employing generic vocabulary with the intent of eliciting precise academic responses from students.

We pose vague questions laden with imprecise terms such as “What’s your idea?” Does anyone else want to share?” or “What answer did your group come up with?” Such generic questions predictably elicit hastily conceptualized and briefly worded responses devoid of adept vocabulary use. Instead, we should be framing our questions very deliberately to focus students’ attention and instill in them a sense of curricular urgency rather than complacency. Consider the lexical precision in the following questions: “What significant observation have you made about the impacts of chronic sleep loss?” or “What is your perspective on this controversial issue?” “Where did you identify the data that led you to draw this conclusion?” Focused questions interlaced with precise terminology support students in comprehending our standards-based focus and implicit expectations. Since the Common Core standards emphasize detailed descriptions, in-depth analysis, evidence-based claims, and well-justified arguments, we should draw from the 21st century literacy skills lexicon (Table 4) as we craft our pivotal lesson questions to guide inquiry and collaboration.

I train my academic English learners to pay careful attention to the words I utilize in my lesson questions and demonstrate how to respond incorporating the focus task word. For example, when asked “From what source did you select this citation?,” “I expect more advanced students to respond in a complete sentence: “I selected this citation from…” Minimally, I coach students with nascent academic English skills to listen attentively as I pose a lesson question, tune in to the target vocabulary (e.g., example, experience, prediction), and respond beginning with the key term instead of the generic response My idea is…: e.g., My prediction is that…My example is…

Moving Toward Accurate Fluency

Advanced, if not native-like proficiency in English, is imperative for language-minority youths whose educational and professional aspirations hinge upon communicative competence in the language of school and the professional workplace. Being able to converse in English with relative ease is not a bold enough instructional goal. The Common Core State Standards, their assessments, and an increasingly sophisticated workplace exert tremendous pressures on language-minority and economically disadvantaged youth to develop accurate fluency, the ability to effortlessly produce error-free, contextually-appropriate language (Dutro & Kinsella, 2010). To actualize the goal of 21st century literacy skills for our increasingly diverse student population, every K-12 educator will need to simultaneously teach rigorous content while modeling and coaching adept academic English register with integrity and tenacity.

References

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Center for Applied Linguistics.

Common Core State Standards (2010). “Applications of Common Core State Standards for English language arts & literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects.” Retrieved from www.corestandards.org

Craig, H.K. & Washington, J.A. (2004). “Grade-related changes in the production of African American English.” Journal of Speech, Hearing, and Language Research, 47(3): 450-463.

Dutro, S., & Kinsella, K. (2010). “English language development: Issues and implementation in grades 6-12.” In Improving education for English learners: Research-based approaches. California Department of Education.

Francis, D., Rivera, M., Lesaux, N., Kieffer, M., & Rivera, H. (2006). Practical guidelines for the education of English language learners: Research-based recommendations for instruction and academic interventions. Portsmouth, NH: RMC Research Corporation, Center on Instruction.

Schleppegrell, M.J. (2001). “Linguistic features of the language of schooling.” Linguistics and education. 12(4): 431-459.

Zwier, J. (2008). Building academic language: Essential practices for content classrooms, grades 5-12. Jossey-Bass.

Kate Kinsella, Ed.D. (katek@sfsu.edu) is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her professional development institutes, publications, and instructional programs focus on career and college readiness for English learners, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading, and writing.

The Texas Computer Education Association (TCEA) Convention and Exposition is in its second day in Austin, with activities running until February 9. TCEA (Texas Computer Education Association) is a global, nonprofit, member-based organization supporting the use of technology in education. Founded in 1980, TCEA has been playing a vital role in increasing technology funding and access for PreK-16 schools for 37 years.

The Texas Computer Education Association (TCEA) Convention and Exposition is in its second day in Austin, with activities running until February 9. TCEA (Texas Computer Education Association) is a global, nonprofit, member-based organization supporting the use of technology in education. Founded in 1980, TCEA has been playing a vital role in increasing technology funding and access for PreK-16 schools for 37 years.

Friday February 8 is the last chance to apply for the study abroad Boren Scholarships. These scholarships promote long term linguistic and cultural immersion, and therefore study abroad proposals for two or more semesters are strongly encouraged. Preference will be given to undergraduate applicants proposing a at least 6 months overseas.

Friday February 8 is the last chance to apply for the study abroad Boren Scholarships. These scholarships promote long term linguistic and cultural immersion, and therefore study abroad proposals for two or more semesters are strongly encouraged. Preference will be given to undergraduate applicants proposing a at least 6 months overseas.

Languages Canada, the country’s national language-education association, has launched a dynamic new web tool for students, parents, agents, foreign governments, and Canadian trade commissioners, which allows users to conduct a personalized search for the accredited language programs that best meet their needs by filtering their criteria.

Languages Canada, the country’s national language-education association, has launched a dynamic new web tool for students, parents, agents, foreign governments, and Canadian trade commissioners, which allows users to conduct a personalized search for the accredited language programs that best meet their needs by filtering their criteria.

Al Jazeera has launched a Mandarin-language news

Al Jazeera has launched a Mandarin-language news

It has been widely thought that humans learn language using brain components that are specifically dedicated to this purpose. However, new evidence strongly suggests that language is in fact learned in brain systems that are also used for many other purposes, which pre-existed humans and even exist in many animals, say researchers in PNAS (Early Edition online Jan. 29 http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/01/25/1713975115).

It has been widely thought that humans learn language using brain components that are specifically dedicated to this purpose. However, new evidence strongly suggests that language is in fact learned in brain systems that are also used for many other purposes, which pre-existed humans and even exist in many animals, say researchers in PNAS (Early Edition online Jan. 29 http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2018/01/25/1713975115).

Johanna Even and Mawi Asgedom help us empower English learners through an

Johanna Even and Mawi Asgedom help us empower English learners through an

The U.S. Department of Education launched a new interactive web page dedicated to data on English Learner students (ELs). The site uses colorful maps, bar graphs, and charts to provide a clearer understanding of America’s diverse ELs population in a “

The U.S. Department of Education launched a new interactive web page dedicated to data on English Learner students (ELs). The site uses colorful maps, bar graphs, and charts to provide a clearer understanding of America’s diverse ELs population in a “