Matt Renwick recommends a grounded approach when it comes to technology in the classroom

Matt Renwick recommends a grounded approach when it comes to technology in the classroom

In a first-grade classroom, two teachers co-facilitated a literacy lesson. It was a shared reading experience that transitioned into a shared writing activity. One of the teachers read aloud a book written in both English and Spanish. This activity was followed by writing a text together that had a similar structure to the original book. As a class, they wrote this first draft on an easel.

Several of these students were English learners. Spanish was their first language; many had already made gains in their acquisition of English. This lesson positioned these kids as experts in the classroom. For example, when the teacher read aloud “piñata,” one of the students, Jesus, responded with a more accurate pronunciation. “Why, thank you, Jesus,” responded the teacher. “Your Spanish is excellent. I appreciate your help on that” (Routman, 2008).

There were many resources available in the classroom to support responsive and differentiated instruction: comfortable seating for both whole-group and small-group learning; high-interest, authentic literature; writing materials for students; easel paper and markers. All students were feeling successful as the teachers thoughtfully played to their strengths. What one would not have found, at least during the lesson, was technology.

Imagine if technology had been a part of this lesson, such as laptops or tablets.

What would the students have gained from this inclusion? How might the teachers’ instruction have been enhanced? A reasonable conclusion would be that technology would not have supported student learning in this lesson. In fact, it could have hampered it. For example, if the teacher projected her computer screen to students’ tablets as she wrote on a digital document, a few students might have lost connection to the wireless. Maybe another student would have tried to pull up a web browser instead of attending to the lesson. Certainly, everyone would have been staring at a screen instead of focusing on each other in this community-enhancing, literacy-rich lesson.

Technology has its place in schools and learning, yet only in specific situations is it necessary. Sometimes the benefits are merely nice. Technology can even have a negative impact on instruction. Try this quick exercise: Think about the past week of instruction. Then mentally remove the technological component(s) of it. Now imagine teaching the same lessons without the technology. Were the students able to learn just as well? Except for a few situations, my guess is the answer to this exercise is yes.

As teachers and school leaders, we need to take a critical approach when considering the inclusion of digital tools in our instruction. Technology providers will promote their products as essential to student learning outcomes. The problem with this approach is most of these providers work for businesses. They likely are not educators; their bottom line is dollars but not always sense. We as professionals are obligated to exercise our professional judgment when determining how to integrate technology into the classroom. The rest of this article describes five myths regarding technology for learning, countered by five truths, along with explanations for these misconceptions.

Myth: Technology is easy to learn and use.

Truth: Teachers need a reason, time, and support to successfully integrate technology.

Any time I see stacks of laptops or tablets being readied for student or staff distribution, the first thing I wonder is, “What preparations have been made to ensure that these computers will be used effectively and seamlessly in instruction?” Too often, no plans have been made other than a brief overview of the basic functions. This can be a recipe for wasted resources and no improvement in learning.

Technology is not necessarily easy to learn or use. Asking a teacher to implement digital tools with success can be a daunting request without a rationale for the technology, the proper training and time to practice, and accessible support. Yet with these elements in place, bringing technology into classrooms and schools can be a worthwhile effort.

A strong rationale for implementing technology is a prerequisite for its implementation.

This type of initiative cannot be about “keeping up with the Jones’s,” such as citing that a neighboring district has gone 1:1. Any purpose for implementing technology in schools has to be about improving teaching and learning. The goal does not have to be broad. In fact, smaller initiatives can increase the likelihood of teachers and students feeling successful.

One possible idea for a strong purpose is having students publish a classroom or school newsletter using Smore, WordPress, or Adobe InDesign. Students can create web-based, content-rich media that closely resembles the real work of the world.

These digital applications have a learning curve, which demands time and support for learners to be successful. The school library media specialist can be a key staff member for this work. In our elementary school, this person visits each classroom once a week to lead a lesson on a specific tool and activity. Library media specialists can also offer monthly after-school sessions for teachers to try out these new technologies in a low-risk environment and plan for how to implement them in the classroom.

Myth: Technology is expensive.

Truth: When upgrading outdated resources, technology can be cost-effective.

The Latin root of the word innovate (innovare) means “to renew or change.” If something new is introduced to a classroom, the assumption is it is replacing an outdated practice or resource. Yet in many schools, technology is instead layered over existing practices, a digital veneer that does not really change instruction.

If technology is purchased for classrooms without forethought as to what it is improving and replacing, this can impair a limited budget at the expense of other essential resources and staff. Something has to give if we believe that the inclusion of digital learning will improve student learning in a way not possible without it.

Some low-hanging fruit in traditional schools that is ripe for being replaced is textbooks. In the 21st century, these compendia of information are immediately outdated the moment they are printed. Today’s technologies can position students and teachers as co-creators of their own knowledge sources.

For example, middle-level teachers can guide students to create Google Sites around important points in history. Open educational resources (OER) such as the National Archives and Smarthistory can be linked into the site as pertinent content to study. Teachers can also develop curriculum with open educational resources using the OER Commons website. If the adage is true that the best way to learn something is to teach it, then having students co-develop learning materials with teachers seems like a smart and cost-effective approach.

Myth: Technology should be in the hands of every student.

Truth: Sometimes less technology can lead to greater student achievement.

For all of the gains students may experience with the addition of technology—for example, a constant connection to a world of information—what might they lose? Quite a bit. As an example, studies have shown that when students have unlimited internet access through their smartphones via social media, their relationships with people in their immediate lives can start to deteriorate (Turkle, 2015).

Additional effects of increased access to the internet include a decrease in school performance and an exacerbation of the achievement gap (Toyama, 2015). This is not to suggest that social media is an absolute negative in students’ lives. Another study which analyzed English learners’ activity on Facebook found the experience to be very positive when they were engaged in conversation and media consumption with people and resources from their countries of origin (Stewart, 2014).

The key here is how students are engaged in learning with technology. This is where a teacher’s expertise is so important. Educators need to understand not only pedagogy and content but also how technology might enhance or distract from the process of learning. Some of the best technology-enhanced lessons I have observed do not feature computers in the hands of every learner.

For example, in my last school, students in groups of three were provided one tablet with the task of creating an original digital nonfiction text. Using the app Book Creator, students were expected to incorporate audio, images, and text to communicate their learning regarding the culture of another country.

They knew their work would be published for an authentic audience through FreshGrade, a digital portfolio application. Students spent lots of time getting their audio recordings right as they read and reread the text. This audio would be embedded in the digital text to ensure that all readers could access their book. The limited access to technology brought students together instead of dividing them. Their deliberate practice with speaking was authentic and improved their fluency. The focus was on content and cooperation instead of the technology.

Myth: Technology improves student learning.

Truth: Without an expert teacher, technology’s impact on learning is minimal.

One type of classroom technology becoming more prominent in schools is intelligent tutoring systems, or ITS. These applications provide feedback for students in real time as they work through math problems or respond to questions about a given text. The idea is that students can learn important concepts and skills without the immediate guidance of a teacher.

The problem with this premise is it does not necessarily work. Technology-enhanced instruction has had mixed results in studies, with enough evidence to encourage caution among educators. However, many studies have shown that when a teacher’s instruction is thoughtfully incorporated with technology, learning can be improved.

In one research study conducted by Filament Games and Sennett Middle School in Madison, WI, the use of video games to teach social-emotional skills in the classroom without teacher guidance only resulted in a 1% improvement in student learning. Teacher-only instruction resulted in a 6% increase in learning, while a combination of the application and teacher instruction resulted in a 10% improvement in student learning (Clardy and Pittser, 2017).

The good news here is that, in the age of technology, teachers are more important than ever. What is critical for the teacher is to become familiar with digital tools and how best to utilize them in the classroom.

Myth: Technology is a distraction.

Truth: Technology is a thing. People are distractible.

A recent trend with technology in education is the banning of smartphones in schools. Whole districts are prohibiting these mini-computers from coming into classrooms due to the perception that they are distracting students from their learning. The thinking goes, kids cannot help themselves from checking their feeds on Snapchat and Instagram if their phones are in their pockets.

I think educators are going to look back on these policies with embarrassment—not because these concerns are unreasonable, but because we avoided having a critical conversation with our students and staff about the influx of mobile technology and the inherent challenges it brings. These problems exist beyond K–12 education. Instead of banning smartphones outright, what if teachers engaged in conversation around these issues, just as they would with any other current event or topic of interest? These discussions could lead to smarter policies that are student-owned regarding how best to regulate and self-monitor the usage of mobile technology.

As an example, teachers can provide choice boards when guiding students to study relevant concepts and themes in depth, such as “solitude.” Links to online content, such as articles, videos, and music, can be represented by QR codes that students scan with their smartphones to watch or listen. They can curate favorite resources using productivity tools such as Evernote and Google Keep to use for research when they later compose essays or presentations on these topics. These studies can conclude with deep discussions about the importance of finding balance in our overly connected lives.

Conclusion: The Future Belongs to the Learner

Education is experiencing growing pains brought on by the influx of technology in classrooms. We are not sure yet what works, which makes us susceptible to fads and initiatives without any evidence of their effectiveness. Educators should not wait for a litany of studies to support the inclusion of digital tools to support student learning. Instead, let us adopt a learner’s mindset and work with our students to discover what is possible with education today. These skills and dispositions will only serve to build our students’ capacities to discern what are and what are not the best approaches for bringing technologies into our lives.

References

Clardy, T., and Pittser, B. “Measuring the Socioemotional Benefits of Game-Based Learning.” Session presented at School Leaders Advancing Technology in Education (SLATE) Convention, Dec. 5, 2017.

Routman, R. Regie Routman in Residence: The Reading-Writing Connection. Online professional development series. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2008.

Stewart, M. A. “Social Networking, Workplace, and Entertainment Literacies: The Out-of-School Literate Lives of Newcomer Latina/o Adolescents.” Reading Research Quarterly 49, no. 4 (2014): 365–369.

Toyama, K. “Why Technology Alone Won’t Fix Schools.” Atlantic, June 3, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/06/why-technology-alone-wont-fix-schools/394727/.

Turkle, S. Reclaiming Conversation: The Power of Talk in a Digital Age. London: Penguin Press, 2015.

Matt Renwick is the author of Five Myths About Classroom Technology: How Do We Integrate Digital Tools to Truly Enhance Learning?, and his latest book is Digital Portfolios in the Classroom: Showcasing and Assessing Student Work (ASCD, August 2017), available at www.ascd.org/Publications/ascd-authors/matt-renwick.aspx. He started as a fifth- and sixth-grade teacher in a country school outside of Wisconsin Rapids, WI, 18 years ago. He then served as a dean of students at a junior high, which developed into an assistant principalship along with athletic director duties. As an elementary principal for the Mineral Point Unified School District, he enjoys the curriculum, instruction, and assessment sides of education. He also teaches online graduate courses in curriculum design and instructional leadership for the University of Wisconsin-Superior.

Literacy rates have not improved in over 15 years, costing the world $1.19 trillion a year and leaving over 750 million people worldwide unable to read this sentence, so Project Literacy Lab, a partnership between Pearson and Unreasonable Group, part of the broader Project Literacy campaign, is bringing a new group of problem solvers to the table: entrepreneurs. This first-of-its-kind international accelerator focuses on scaling up ventures that are positioned to help close the global literacy gap by 2030.

Literacy rates have not improved in over 15 years, costing the world $1.19 trillion a year and leaving over 750 million people worldwide unable to read this sentence, so Project Literacy Lab, a partnership between Pearson and Unreasonable Group, part of the broader Project Literacy campaign, is bringing a new group of problem solvers to the table: entrepreneurs. This first-of-its-kind international accelerator focuses on scaling up ventures that are positioned to help close the global literacy gap by 2030.

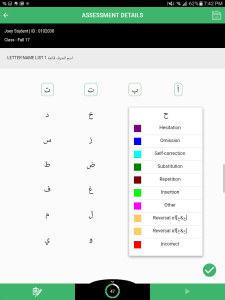

Diglossia has announced the release of Mubakkir, an Arabic early-reading assessment designed for native and nonnative learners at beginning and intermediate proficiency levels. Experts agree that early and frequent measurement of young learners’ progress toward the acquisition of early literacy skills is an essential element for developing successful readers and writers, and the test addresses a need in the MENA region for a standards-based Arabic early-literacy assessment.

Diglossia has announced the release of Mubakkir, an Arabic early-reading assessment designed for native and nonnative learners at beginning and intermediate proficiency levels. Experts agree that early and frequent measurement of young learners’ progress toward the acquisition of early literacy skills is an essential element for developing successful readers and writers, and the test addresses a need in the MENA region for a standards-based Arabic early-literacy assessment. “We are honored to partner with the Arab Thought Foundation on Mubakkir, the first online test to measure literacy development in Arabic language learners. Early literacy skills are critical in preparing children for success in school and in life, and Mubakkir gives educators the data necessary to ensure achievement for early Arabic readers. The test furthers our commitment to partner with MENA educational organizations in realizing our shared goal of supporting Arabic language literacy throughout the world.”

“We are honored to partner with the Arab Thought Foundation on Mubakkir, the first online test to measure literacy development in Arabic language learners. Early literacy skills are critical in preparing children for success in school and in life, and Mubakkir gives educators the data necessary to ensure achievement for early Arabic readers. The test furthers our commitment to partner with MENA educational organizations in realizing our shared goal of supporting Arabic language literacy throughout the world.”

Does one have to speak Spanish to be considered Hispanic or Latino in the U.S.? What is the role of Hispanic media in the country which elected Donald Trump a year ago? How important is the Spanish language to Hispanic media? How does such media affect the use of Spanish in a country with 58 million Spanish speakers?

Does one have to speak Spanish to be considered Hispanic or Latino in the U.S.? What is the role of Hispanic media in the country which elected Donald Trump a year ago? How important is the Spanish language to Hispanic media? How does such media affect the use of Spanish in a country with 58 million Spanish speakers? Lisa Hagan takes the mystery out of biometric testing for international English language test takers

Lisa Hagan takes the mystery out of biometric testing for international English language test takers While many schools are dropping foreign language classes, the number of schools offering Mandarin Chinese courses is rising. In 2001, about 300 schools in the U.S. taught Chinese. In 2011, a con-servative estimate reported the number at 1600, a 433% increase. Schools that cannot afford Mandarin classes may be eligible to receive sponsorship from the Confucius Classroom program. China’s place as a global superpower is not only a household conversation but an educational one, too.

While many schools are dropping foreign language classes, the number of schools offering Mandarin Chinese courses is rising. In 2001, about 300 schools in the U.S. taught Chinese. In 2011, a con-servative estimate reported the number at 1600, a 433% increase. Schools that cannot afford Mandarin classes may be eligible to receive sponsorship from the Confucius Classroom program. China’s place as a global superpower is not only a household conversation but an educational one, too.

U.S. K-12 schools can host a fully-funded teacher from Egypt, Morocco, or China with the help of Teachers of Critical Languages Program (TCLP) grants. TCLP is fully-funded grant sponsored by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State. Through TCLP, schools can start new critical language programs or expand existing programs by hosting teachers of Arabic or Chinese as a foreign language.

U.S. K-12 schools can host a fully-funded teacher from Egypt, Morocco, or China with the help of Teachers of Critical Languages Program (TCLP) grants. TCLP is fully-funded grant sponsored by the Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs of the U.S. Department of State. Through TCLP, schools can start new critical language programs or expand existing programs by hosting teachers of Arabic or Chinese as a foreign language.