Kate Kinsella offers an action plan to encourage second language learners to participate in constructive classroom discussion

A primary goal of English language development and world-language coursework is to ensure that students develop the verbal and written language skills to communicate effectively in social and academic settings. To develop communicative competence, students at all grade levels and proficiency levels need daily supported opportunities using their second languages for diverse purposes. Simply providing provocative questions and exhortations to “share with a neighbor” will not yield impressive linguistic results. In this frequent classroom scenario, students are likely to respond inefficiently and inaudibly, using brief phrases punctuated by everyday vocabulary, without being able to recall their lesson partners’ contributions.

To make second-language strides, all students benefit from lessons that increase the quantity and quality of their verbal and written responses. Integrating routine classroom interactions that significantly improve students’ language and literacy skills is both a science and an art. In heterogeneous classes including a wide range of attitudes and abilities, it makes sense to structure routine partner interactions as a platform for more confident and competent lesson contribution. Drawing on years of experience teaching English learners and world-language students, I have compiled some instructional imperatives for orchestrating promising academic interactions with lesson partners that bolster engagement in subsequent unified-class discussions.

1. Gather Data on Student Work-Style Preferences

Experience as a second-language educator and classroom research illustrate how anxiety-provoking it can be for neophyte English speakers and world-language students to be directed to “get with someone” to complete a lesson task. In fact, my earliest forays into structuring collaborative tasks in high school French and English language development courses were met with such resistance that I eventually designed a survey to allow my language scholars to voice their lesson work-style preferences (Kinsella, 1996; 1997; 2011).

This qualitative classroom-research tool enables students to clarify whether they appreciate more routine opportunities to work on lesson tasks independently, with a partner, or with a group, and under what circumstances. It isn’t intended to serve as a justification for omitting lesson collaboration or independent tasks, but rather, as a practical vehicle to launch a candid discussion regarding the diversity in preferences voiced by classmates and the value in being self-aware, flexible, and mindful of others’ strengths and needs to successfully navigate school and the workplace. One consistent finding in secondary- and higher-education classrooms has been that most students are not inherently opposed to working with others but prefer to do so with a focused and collegial partner far more frequently than a group. Another reliable collective preference is for the teacher to assign partners rather than leave it to students’ initiative or fate.

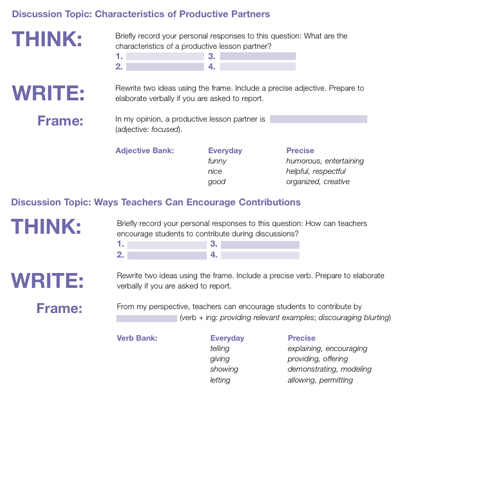

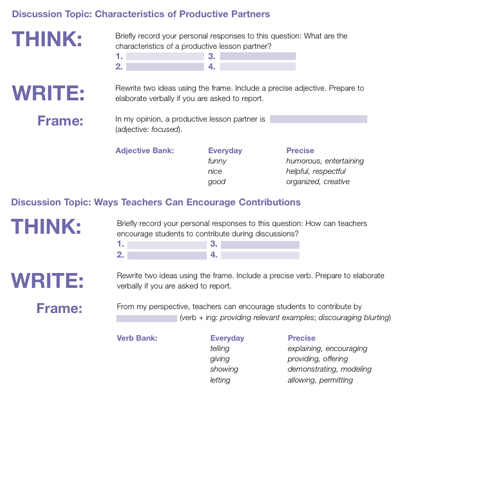

An additional efficient and engaging method to gather data about students’ classroom collaboration experiences and preferences is to assign a brief, focused writing prompt, followed by a unified class discussion. The following academic discussion and writing prompts have served as curricular mainstays in my beginning-of-the-year endeavors to solicit formative input from my second-language students, particularly English learners. Students gain insights and validation as they voice perspectives regarding the attributes of a productive lesson partner and the ways in which a teacher can facilitate more democratic lesson discussions. Providing a sentence frame and precise word bank decreases interaction anxiety for less confident students while increasing accurate oral fluency and listening comprehension.

2. Arrange Classroom Seating

For students to interact efficiently and effectively, they need to be seated in close proximity to a productive classmate while also being able to easily establish eye contact with their teacher and reference any visual lesson displays. Apprehensive contributors may consciously avoid interaction by sitting on the periphery of the classroom, while others may artfully dodge participation by retreating within a social cohort and relying on more loquacious or risk-taking peers.

Prepare your classroom for routine partner and group interactions by first making optimal use of your space and furniture.

• For partner interactions, arrange desks in paired rows approximately one foot apart, leaving an aisle for you to easily maneuver, monitor interactions, redirect idle or off-task students, coach language use, and offer supportive feedback.

• If you are using small tables, assign students to work with an elbow partner (adjacent) or face-to-face partner (across).

• For group interactions, use tables or arrange desks in groups of four, with students facing each other. Make sure the tables or clus-

tered desks are positioned perpendicular to the front of the room so no students have their backs to their teacher or lesson references.

3. Assign Appropriate Lesson Partners

Years of teaching English learners and world language students across the K–12 and college spectrum have helped me grasp the complexities of structuring productive student interactions in a language they have yet to master.

• Assign letters (A/B) for partners in order to easily reference who should speak or complete a particular task first. For example, use rows of desks to assign partners. All students in row one are partner A, row two are partner B, row three are partner A, row four are partner B, and so on. You can also use students’ proximity to areas or items in the classroom. Partner As are seated closer to the clock. Partner Bs are closer to the door.

• Assign numbers (one to four) for group members. Tell students the order to number off and who starts. Number off one to four going clockwise. The group member seated closer to the clock is number one.

• Ask students to confirm their numbers or letters. So where are my partner As? Raise your hands? Partner Bs?

• Keep students working with assigned partners or group members for an adequate amount of time to develop a comfortable and promising working relationship but not so long as to become tedious or exclusive (e.g., two weeks, one month, one entire unit vs. an entire semester).

• Consider student needs when assigning partners, particularly early in the year when they are less familiar with their classmates and teacher expectations for dynamic interaction throughout a lesson. Factors to take into consideration include: second-language proficiency, reading proficiency, maturity level, ability to focus, gender, personality, confidence, and attendance.

• Pair or group compatible classmates within a reasonable range of language and literacy proficiency. Avoid partnering students with extreme skill inequities (e.g., highest performing with least confident and prepared) or students with similar challenges (e.g., extremely inhibited; struggling readers; easily distracted). Don’t rely on your most advanced students to largely serve in a tutorial capacity during lesson interactions. They need to stretch their cognitive and linguistic muscles as much as less proficient or engaged classmates. If a student is exceptionally underprepared and unable to function as an equal partner on lesson tasks, assign that individual to work as an additional partner B with a pair capable of demonstrating both social and academic skills. When partner Bs share ideas, direct both Bs to take a turn. The less confident scholar is better poised to benefit from the linguistic and behavioral models than in a one-on-one collaboration.

4. Justify Daily Integration of Interactive Tasks

Teachers serving English learners have a dual responsibility to advance their students’ content knowledge and English language proficiency. Similarly, world-language teachers are charged with advancing their scholars’ confidence and competence in a language many have few opportunities to hear and use outside the classroom.

Second-language educators might reasonably assume that their acolytes perceive the inherent value in daily lesson interactions. However, few students have difficulty recalling less than rewarding experiences collaborating with classmates across grade levels and subject areas. One predictable source of frustration is being thrust into an interactive and graded lesson task without clear justification, process, evaluation criteria, and monitoring.

• Provide a compelling rationale for including partner and group tasks and interactions in your lessons. My course objective is to ensure that you develop a deeper understanding of your second language and that you can comfortably use a greater range of words and sentences to speak, listen, read, and write. You won’t become a powerful communicator sitting quietly filling in blanks on worksheets or passively watching videos. From my perspective, your partner and group interactions are the most important parts of our lessons. This is where you will apply newly taught language in creative contexts, learn with and from your peers, and gain greater insight into your capabilities and areas in need of improvement.

• Make connections to career and college readiness. Knowing how to interact with a classmate, coworker, teacher, manager, club director, or community member is essential to academic, professional, and social success. Just as in the workplace, college coursework, and community organizations, this collaboration and sharing of ideas will help you refine your understandings and improve your communication. All of you noted in your class surveys that you had great aspirations after graduation. You are interested in careers as diverse as architecture, nursing, and programming. Any and every job description in these professions specifies an individual eager to work and capable of working with individuals from diverse backgrounds.

• Establish your active coaching and monitoring role during structured interaction. Don’t utilize collaboration time as an opportunity to accomplish grading, clerical tasks, or lesson preparation. As you work together, I will be actively monitoring to see if you are having difficulty with any aspect of this assignment. I will be listening to your contributions and reading what you have written. I may ask you to elaborate on a response, clarify what you mean, or restate audibly if you have spoken too softly. I may also ask you to launch our unified-class discussion with a particular response or invite you to contribute a specific idea when I open the discussion to volunteers.

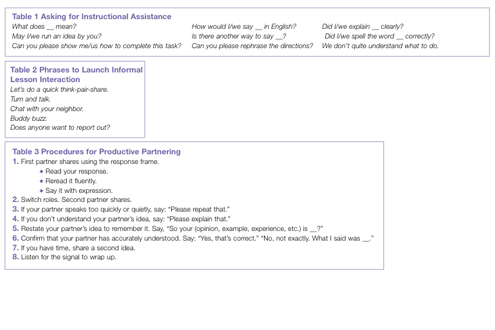

• Provide students with clear guidance on how to request instructional assistance. Reticent or underprepared second-language students will be more inclined to solicit help from a teacher if they have a clear protocol and language tools. Visibly display an array of statements and questions to ask for assistance such as those included in Table 1. As you work together, feel free to call me over to assist you if you have specific questions or needs. Simply raise your pen and make eye contact to attract my attention, and I will come to your table right away. Please don’t simply surrender your assignment to me. Be prepared to explain what you are struggling with and how I might be of assistance. Ask a specific question, like those I have posted to appropriately ask for assistance.

5. Develop Familiar Phrases to Launch an Academic Discussion

By the time students have reached upper-elementary coursework, foundational years of conditioning have taught all too many that when the teacher throws a question or prompt to the classroom stratosphere, they are rarely obliged to contribute or listen attentively. Many have figured out that if they wait but a few seconds, either a “professional participant” or the teacher will eventually respond, letting them off the proverbial hook. Even imploring requests from the teacher such as “Does anyone else want to share?” can do little to engender enthusiastic or competent contributions from apprehensive lesson spectators. In second-language classrooms, every student needs daily and equitable opportunities to engage with the teacher and fellow classmates to make linguistic strides.

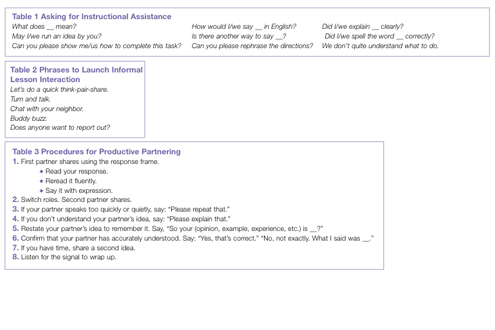

Because so many students approach second-language interaction with trepidation and strategies for evading engagement, it warrants retooling our phrasing for launching a discussion. As a teacher and instructional coach, I have observed that the discussion facilitator’s body language and verbal cues can signal either accountable academic interaction or informal voluntary responses. To illustrate, if the teacher sits cross-legged on a stool or desk and directs students to “Do a quick think-pair-share” in response to a question delivered verbally, few will immediately segue into a scholarly and democratic exchange of ideas. In contrast, standing and pointing out a visibly displayed question, after specifying that you will be facilitating a discussion preceded by partner brainstorming, is far more likely to set the tone that this is a lesson responsibility, not a response option. In my experience, certain widely used questions and requests act as discussion enders and are best avoided if the goal is democratic reflection, thoughtful contribution, and attentive listening. Table 2 includes a number of expressions I have found to elicit informal, unaccountable interaction as opposed to setting the tone for a more formal and inclusive lesson discussion. Using consistent and familiar phrasing to launch an essential discussion improves lesson pacing and student engagement.

6. Establish Procedures for Productive Partnering

When students are assigned a brief partner discussion task, many engage in inaudible “speed mumbling,” completing the interaction as hastily as possible without demonstrating authentic listening. Before the teacher has even had time to break away from the board to monitor student output, most have wrapped up efficiently and are visibly idle, anxiously awaiting the next lesson phase.

To reach higher proficiency levels, second-language students need abundant practice speaking, listening, and receiving timely and productive feedback from the teacher and peers. To maximize language production and improve listening during partner interactions, students benefit from clear, consistent protocols for lesson exchanges. In mixed-ability classes including striving readers and less proficient language users, one reasonable accommodation is to require sharing a response more than once to build both reading and oral fluency. If students have written a response, reading it twice, then saying it with expression primes them for more confident discussion delivery in the event that they are asked to report. Typically, after a hasty partner idea exchange with no feedback loop, a student is no better poised to contribute confidently in a unified-class format.

The sample procedures for partnering in Table 3 have dramatically increased language production in second-language classrooms while affording the teacher adequate time to monitor responses, provide feedback, and preselect a few habitually reticent contributors for the subsequent unified-class reporting.

7. Diversify Strategies to Elicit Participation

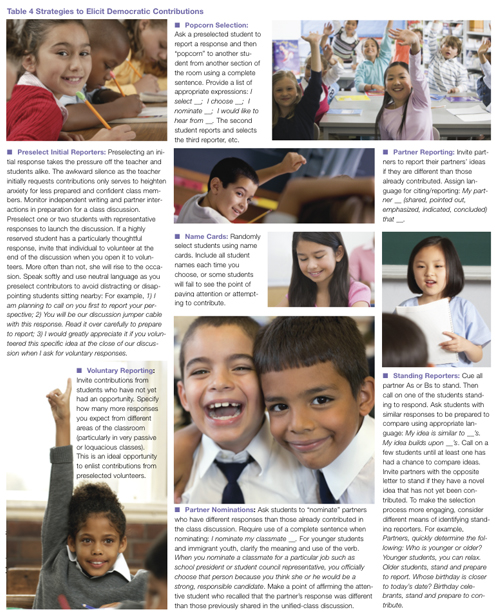

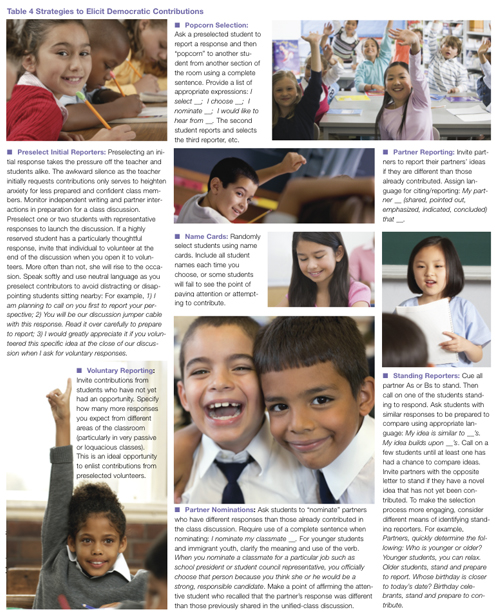

Every language teacher dreads ulcer-inducing classroom scenarios, trying in vain to elicit a range of responses from overzealous and habitually passive alike, reducing the lesson to a glacial pace. There are a number of practical strategies language educators can utilize to reduce student anxiety about contributing in a second language while broadening the customary response pool.

A structured partner exchange with a linguistic scaffold such as a response frame serves as a productive means of rehearsal for unified-class discussion. An opportunity to articulate a response and receive immediate partner feedback goes a long way toward bolstering confidence for contributing in a larger, more intimidating forum. As partners exchange ideas, the teacher can assess the range of responses and enlist the few habitually reticent reporters. Table 4 outlines an eclectic array of strategies second-language educators have utilized from primary grades to adult-education contexts to facilitate more animated and varied class discussions.

Conclusion

Pairing or grouping underprepared English speakers and world-language scholars for productive lesson interactions clearly involves far more than a modified seating arrangement and informal invitations to talk. Increasing miles on the tongue of every aspiring second-language student cannot be left to chance. Our increasingly high-stakes educational standards and assessments in tandem with a competitive global workplace place greater demands on students to be agile, competent communicators, ideally in more than one language. Devoting greater time and attention to structuring supported and accountable interactions in every lesson will increase the odds that the majority of our students, not simply an elite minority, leave our classrooms with the language tools to realize their aspirations.

References

Kinsella, K. (2011, 2014). English 3D: Course I & II. Scholastic.

Kinsella, K. (1997) “Developing ESL Classroom Collaboration to Accommodate Diverse Work Styles.” In Reid, J. (Ed.) Understanding learning styles in the ESL/EFL classroom. Prentice Hall.

Kinsella, K. (1996). “Designing Groupwork that Supports and Enables Diverse Classroom Work Styles.” TESOL Journal, 6 (1), 24-30.

Kate Kinsella, EdD ([email protected]), is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her numerous publications and programs focus on career and college readiness for academic-English learners and under-resourced students, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading, and constructed written response.

Johanna Even and Mawi Asgedom help us empower English learners through an

Johanna Even and Mawi Asgedom help us empower English learners through an

The U.S. Department of Education launched a new interactive web page dedicated to data on English Learner students (ELs). The site uses colorful maps, bar graphs, and charts to provide a clearer understanding of America’s diverse ELs population in a “

The U.S. Department of Education launched a new interactive web page dedicated to data on English Learner students (ELs). The site uses colorful maps, bar graphs, and charts to provide a clearer understanding of America’s diverse ELs population in a “

Clifton Pye suggests a comprehensive approach to crosslinguistic research

Clifton Pye suggests a comprehensive approach to crosslinguistic research

According to a new study published in Child Development, bilingual children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are better at switching from one task to another than their monolingual peers.

According to a new study published in Child Development, bilingual children with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) are better at switching from one task to another than their monolingual peers.