Language Magazine asks luminaries in the EdTech landscape what to expect and what we can hope for in 2018

Language Magazine asks luminaries in the EdTech landscape what to expect and what we can hope for in 2018

I am hoping that school district leaders increasingly focus on making the most of the amazing technology that has emerged to instruct and improve student outcomes. I am also looking to see a positive spillover effect in 2018 from current conversations on how new classroom spaces can be designed to advance student learning.

Importantly, too, I am hopeful that special education staff increasingly will be included in these discussions from the jump, so that chief technologists and pupil-services administrators can meaningfully collaborate to select the right technology for the widest range of students—as opposed to trying to retrofit technology to meet student needs. Focusing on how EdTech can be used to advance students’ literacy and language skills is a critical part of this conversation.

Moreover, I am anticipating and looking forward to an abundance of high-level professional learning opportunities in 2018 for using technology and innovative classroom design to better serve K–12 students. This anticipation is the result of having just developed the Future of EdTech Special Education session track for the 2018 National Future of Education Technology Conference (FETC), as well as having overseen development of a parallel Information Technology session track for chief technologists. The collaboration, guidance, brainstorming and problem solving that will occur at FETC in January—particularly among high-level K–12 leaders including superintendents, IT directors, and CAOs—will set the tone for year-long staff development efforts in schools across the country.

Perhaps of most interest to readers of this publication, FETC programming will explore numerous emerging best practices for improving literacy acquisition and overall student outcomes. A featured FETC session titled How EdTech Can Fill the LD Gaps is just one example, where experts will provide insights to help the field adapt to the needs of students with learning challenges. Attendees also have the opportunity to attend deep-dive workshops and concurrent sessions on how to access free resources to help students who struggle with reading and writing; employ digital games to help students develop literacy, life, and career skills; and use adaptive technology to inform ELA instruction.

Overall, I am anticipating that 2018 will be a year in which conversations in education predominantly center on how to create active learning experiences and spaces for students of all abilities.

Steve Bevilacqua, editorial and content sponsorship director, FETC

Are We Living in the Jetsons’ Future?

While I have often heard people lamenting the fact that we do not yet have the flying cars from the TV cartoon The Jetsons, I think it is time for us to realize that much of what was shown as “the future” in that show is technology we use every day. After all, just ten years ago, we could not imagine the transformation that would occur from:

- Smartphones

- Facebook

- YouTube

- Uber

- Netflix

- Crowdfunding

- Cloud storage

- Virtual reality

This trend of the future happening right now is only going to increase in 2018. So, what can we expect to see?

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Our devices are getting smarter. Now, instead of having to tediously open an app to see what the weather will be in my location tomorrow, I simply need to ask my favorite artificial assistant—whether that is Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa, or Google’s Home. Instead of opening my calendar on my computer and seeing if I have an open time slot, I just ask my artificial assistant to do it for me.

Artificial intelligence will become more prevalent in 2018, especially in the job market. A new Forester Research report states that in 2018, “AI-enabled automation will eliminate 9% of US jobs.” The jobs most impacted will be in call centers, administration, and sales. Education will need to help retrain those who lose their jobs, causing a growth in community colleges and online courses. Skills for new jobs that will need to be learned include drone automation, designing entertainment for driverless transportation, robot programming, and computer coding.

Autonomous Robots

While we will not see Rosie the Robot cooking meals in our homes just yet, we will see a great increase in the robotic service industry. Domino’s Pizza and other fast-food chains aggressively research the use of robotic labor for food preparation and delivery. To get an idea, check out Flippy, the kitchen assistant. Or take a look at SAM, the semi-automated mason, who can lay 3,000 bricks a day.

What will the growth of robots mean for education? Someone has to program these devices and perform troubleshooting and maintenance on them. This is a career that is guaranteed to expand over the next ten years and one for which we should be preparing many of our students. To help us understand how the labor force will change as a consequence of the rise of the robotic labor force, take a look at the slightly tongue-in-cheek website Will Robots Take My Job? Enter any job, like short-order cook, and see the likelihood that a human will no longer be performing this task in the future.

Augmented and Virtual Reality

A natural step up from current interactivity, AR (augmented reality) and VR (virtual reality) additions to learning modules will become more prevalent in 2018. Instead of just watching the heart pump in a video, now students can be a blood molecule flowing through the chambers in a virtual reality simulation. Learning about the Civil War? Take on the role of a Confederate soldier at Gettysburg with just a pair of VR goggles and a cell phone. Learning becomes more immersive as AR, VR, and AI combine to allow students to experience and create. As the technology becomes less expensive and new boundaries are explored, AR/VR will be accessible to more students around the globe, allowing learning to become a more social activity in which students can learn together virtually.

The Internet of Things (IOT)

Connecting anything to the internet so that it can be controlled over distance has tremendous possibilities for schools. Implemented fully, it can improve efficiency and reduce costs. But it also provides more ease of use and greater access to information. For example, if each school bus is connected to the IOT, then parents can always know where their child’s bus is at any given moment using an app. “Smart” payment systems will allow students to pay for school lunches and for parents to add money to their accounts with just a fingerprint. Automatic attendance tracking, temperature sensors, smart HVAC systems, and more will become more widespread.

The need for increased bandwidth to manage all the devices connected to the internet will drive how soon education will be impacted by IOT. Once these challenges are met, greater student engagement, more timely data, more powerful mobile learning, and a safer learning environment will be the result.

I think that, if George Jetson and his family walked into our world today, they would feel right at home. As educators, we need to make sure we are doing everything we can to feel at home in this future and to help our students be the most prepared they can possibly be for what is coming next.

Lori Gracey, TCEA executive director

Unveiling the Force of Learner-Initiated Informal Language Learning: Extramural Learning

It is an established fact that learning a second or foreign language (L2/FL) can take place both inside and outside an educational context (Benson, 2011; Gee, 2007; Peterson, 2010; Reinders, 2012). In recent years, it has been suggested that the learning of L2/FL English may be decisively improved through exposure to and use of English outside institutional settings, so-called extramural English (EE), which has been defined as learner-initiated, informal, voluntary activities mediated in English, such as playing digital games, listening to music, watching television or films, and reading (Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2016). Recently, a number of studies have provided empirical evidence of learning taking place thanks to EE among young learners (Duursma, Meijer, and de Bot, 2017; H. Jensen, 2017; Kuppens, 2010; Lefever, 2010; Sundqvist and Sylvén, 2014; Sylvén and Sundqvist, 2012), teenagers (Brevik, 2016; Brevik and Hellekjær; Sundqvist and Wikström, 2015), and adults (Sockett and Toffoli, 2012).

While EE has already become a recognized factor for L2/FL English learning in European countries, especially in the Nordic countries, the Netherlands, and Belgium, in many other countries it remains an unknown source for and path to learning English. However, scholars in the South Asian region have recently begun looking into EE as a possible resource for L2/FL English learning too (see, e.g., Stockwell, 2013), and we predict a similar type of development there with regard to the role of EE for learners of all ages.

Our explicit wish for the coming year(s) is that EE become acknowledged worldwide as the language-learning goldmine it in fact is. Neglecting the exposure to and use of English in, for instance, social media and digital games is detrimental to both teaching and learning. However, acknowledging the vast learning possibilities of EE by, for instance, letting students talk about their experiences of EE in class will make students aware of the fact that while being engaged in some activity solely grounded in their own private interests, they learn English at the same time, because this is what research has shown (cf. the empirical studies mentioned above). Teachers who plan for and invite discussions of such learning experiences in their classrooms are guaranteed to see EE-experienced students offer personal and generally successful “learning stories” to peers who are yet to discover the potential of EE.

As a bonus, by becoming aware of the various kinds of EE their own students have experience of, teachers will be better prepared to individualize teaching, which is often necessary today considering students’ diverging proficiency levels in English (sometimes linked to individual difference variables, but also to varying degrees of involvement in EE). By gaining knowledge of their own students’ EE preferences, teachers have the opportunity to take student learning further into the academic realms of language, which are more rarely encountered through EE. Thus, this is where English language instruction and school will play a crucial role in the future.

On a final note, though we have focused on extramural English in this short piece, we would like to point out that it is naturally possible for learners to initiate activities voluntarily in any language (Ln), especially in technologically advanced societies where access to innumerable languages is just a click away. For example, there appears to be evidence of learning from extramural Japanese among university students in Sweden, much thanks to online resources of Japanese (Bengtsson, 2014). In closing, we think the time is ripe to start talking about extramural Ln as a specific field of L2/FL teaching and learning.

Pia Sundqvist and Liss Kerstin Sylvén are professors at Karlstad University and University of Gothenburg, Sweden, respectively. More information on them and the references for this piece can be found online at www.languagemagazine.com/references-fulfilling-technological-promise.

Pia Sundqvist holds a PhD in English linguistics from Karlstad University, Sweden, where she is associate professor of English. Her research interests are out-of-school, extramural informal English language learning, CALL (especially gaming), L2 vocabulary acquisition, and assessment of L2 oral proficiency, with a focus on primary and secondary school learners. Email: [email protected]

Liss Kerstin Sylvén holds a PhD in English linguistics from the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, where she is professor of language education. Her research interests are second-language learning through content- and language-integrated learning (CLIL), extramural exposure, and CALL, with a special focus on individual learner differences. Email: [email protected]

Looking ahead to 2018, I am encouraged to see the proliferation of dual-language programs throughout the U.S. When students can learn some of their school subjects in English and others in a foreign language, the advantages are demonstrated and clear. Students do better in reading (in English!) and math, and eventually outperform peers who are not in dual-language settings in just about every subject.

We live in a global world where people interact with different cultures and languages daily; they need this skillset to thrive in a competitive workforce in which communication is critical. In 2018, I hope that more people’s eyes are opened to the fact that study of a foreign language actually improves student achievement in other subjects. The rest of the world is far ahead of us in this respect and not only encourages proficiency in multiple languages but requires it in order to graduate.

I am encouraged by the fact that 29 states and the District of Columbia now offer the Seal of Biliteracy to students earning high school diplomas. Students who receive the seal must demonstrate, either via classroom or a test, that they can communicate in two languages. In 2017, six states adopted the seal. Approximately a dozen more states are currently considering adding the seal or are in the early stages of adoption. Here’s hoping that we can get half of those states to join in 2018. This Seal of Biliteracy is just one important way to get students, teachers, and schools focused on the benefits of language learning and to put in the long hours of time and effort required to become proficient in a second language.

I see a lot of room for technology to expand language-learning opportunities for students enrolled in dual-language programs as well as in more traditional ones, and I hope that an increased embrace of technology in language teaching and learning is something we will see in 2018. We also continue to see an increase in the number of businesses around the globe that are working with Rosetta Stone to implement language-training programs for employees. Learning does not just stop once you leave school; it is important to continually build skills to keep you competitive; this will carry you in your career. It is encouraging to see that global companies value this in their workforces.

For example, I am eager to see how cutting-edge technologies like virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) can be incorporated more fully into the teaching and learning of languages and cultures. VR has the capacity to make you feel like you are really there—whether “there” is a Parisian café, an open-air market in Mexico, or the Coliseum in Rome. That immersive environment, paired with a puzzle to solve and sympathetic real people and believable characters to work with, should prove a very engaging way for people to practice and learn another language. Later, when they are finally in the country, using their new language, students can use AR to take what they have learned out into the real world. The technology can help them interact with native speakers and learn about their surroundings, deepening their experience and facilitating their exchanges with others.

Even if we do not get as far as introducing VR and AR into classrooms in 2018, I hope that more people will open their eyes to the possibilities technology already offers. When I was studying French as a teenager, I had to ask my parents for a short-wave radio as a holiday gift, because it was the only way I was going to be able to get French-language broadcasts on demand.

Today, students can access all manner of authentic materials in the language (and style) of their choice. Whether they like rap, pop, or rock music, comedy shows, crime thrillers, or artsy movies, variety shows or cartoons, they can find on the internet more content than they could ever consume. This content can help them learn the language and the culture simultaneously. Language teachers can use it to bring the language alive and make their class the one students look forward to every day.

Most of all, I hope that in 2018 more people will realize how learning a new language can improve communication with others—whether it is a classmate from another country, a coworker or customer halfway around the world, or the person next to you on the bus. Language skills can help us better understand each other in this increasingly connected yet somehow more divided world. Here’s hoping that 2018 will bring more opportunities for mutual understanding through the appreciation of other languages and cultures.

Dr. Lisa Frumkes, senior director of content development, Rosetta Stone

Amanda Cuellar shares the benefits of learning via smartphone for adult English language learners

Amanda Cuellar shares the benefits of learning via smartphone for adult English language learners

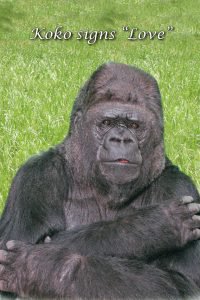

Koko—the gorilla known for her extraordinary mastery of sign language, and as the primary ambassador for her endangered species—passed away yesterday morning in her sleep at the age of 46.

Koko—the gorilla known for her extraordinary mastery of sign language, and as the primary ambassador for her endangered species—passed away yesterday morning in her sleep at the age of 46.

A new study, “Goldilocks Effect? Illustrated Story Format Seems ‘Just Right’ and Animation ‘Too Hot’ for Integration of Functional Brain Networks in Preschool-Age Children,” suggests a “Goldilocks effect,” where audio may be “too cold” at this age, requiring more cognitive strain to process the story, animation “too hot,” fast-moving media rendering imagination and network integration less necessary, and illustration “just right,” limited visual scaffolding assisting the child while still encouraging active imagery and reflection. The study is the first to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to explore the influence of story format (audio, illustrated, animated) on the engagement of brain networks supporting language, visual imagery, and learning in preschool-age children.

A new study, “Goldilocks Effect? Illustrated Story Format Seems ‘Just Right’ and Animation ‘Too Hot’ for Integration of Functional Brain Networks in Preschool-Age Children,” suggests a “Goldilocks effect,” where audio may be “too cold” at this age, requiring more cognitive strain to process the story, animation “too hot,” fast-moving media rendering imagination and network integration less necessary, and illustration “just right,” limited visual scaffolding assisting the child while still encouraging active imagery and reflection. The study is the first to use magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to explore the influence of story format (audio, illustrated, animated) on the engagement of brain networks supporting language, visual imagery, and learning in preschool-age children. Brooke Foged and Jenny Hammock share their insights into fighting generational illiteracy with the engaging power of technology

Brooke Foged and Jenny Hammock share their insights into fighting generational illiteracy with the engaging power of technology

Language Magazine asks luminaries in the EdTech landscape what to expect and what we can hope for in 2018

Language Magazine asks luminaries in the EdTech landscape what to expect and what we can hope for in 2018 A new study finds that scores from students who speak a language other than English at home have improved dramatically over the last 15 years

A new study finds that scores from students who speak a language other than English at home have improved dramatically over the last 15 years Language Resources for Teachers & Schools

Language Resources for Teachers & Schools News reports on a new study which shows that early use of words and grammar determines overall student success

News reports on a new study which shows that early use of words and grammar determines overall student success Amid all the talk of fake news, misinformation, and abuse of personal information, the ongoing battle to save net neutrality has been pushed to the background. The net neutrality rules, which passed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2015, prevent broadband and wireless companies from blocking or slowing internet traffic. Surveys show that a majority of the public supports net neutrality and, as the internet becomes more crucial to the provision of fundamental public services like education, its neutrality is in the national, and international, interests.

Amid all the talk of fake news, misinformation, and abuse of personal information, the ongoing battle to save net neutrality has been pushed to the background. The net neutrality rules, which passed the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in 2015, prevent broadband and wireless companies from blocking or slowing internet traffic. Surveys show that a majority of the public supports net neutrality and, as the internet becomes more crucial to the provision of fundamental public services like education, its neutrality is in the national, and international, interests.