Bruce B. Brown examines how independent reading can transform the oute to English language acquisition

Bruce B. Brown examines how independent reading can transform the oute to English language acquisition

Whether in the elementary grades or adults in higher education, for English language learners (ELLs), reading is the most important skill to acquire and master (Alsamadani, 2011; Carrell, 1989). Along with the necessary skills of comprehension and fluency, reading helps ELLs develop and build essential vocabulary necessary for succeeding in school. English as a second language (ESL) research has long been interested in the various aspects of reading and its effects in comprehension and understanding (Alsamadani, 2011; Schell, 1991). According to Schell, 1991, there are two prerequisites for optimal reading growth: quality instruction, and adequate independent or recreational reading time. The main focus of this article is to determine how independent and recreational reading contributes to an effective reading program, while it will also provide suggestions as to how instructors may incorporate independent and recreational reading into erudition.

Independent and Recreational Reading Efficacy

Independent and recreational reading has been around since the invention of writing and has evolved into many forms of pleasurable reading throughout history.

Recreational reading can be defined as students reading by choice rather than as a result of tasks assigned by teachers (Hughes-Hassel & Lutz, 2006). Independent reading, on the other hand, covers a broader spectrum, which permits readers to explore a wider range of materials, assigned or pleasurable, for the purpose of obtaining knowledge and information.

According to many studies, the establishment of independent reading programs in schools, such as allotting free, uninterrupted, independent reading time, can improve various reading skills. Some of these skills include increasing students’ fluency and comprehension, as well as increasing vocabulary. Research also indicates a strong relationship between independent and recreational reading and school achievement (Allington, 2006; Hughes-Hassel, & Ludtz, 2006; Krashen, 2004).

Several studies have been conducted on independent or recreational reading. In one such study, Kelly and Kneipp (2009) explored the relationship between recreational reading and creativity in students. Creative students are students who have a rich fantasy life and enjoy fantasy-related activities. Through independent reading, students increase their creativity and, hence, increase their awareness of experiences, are more inspired, and invoke personal and emotional reactions. Kelly and Kneipp (2009) concluded that recreational reading develops creativity in students, which increases general knowledge, writing skills, and overall academic achievement.

Hughes-Hassell and Lutz (2006) surveyed 214 middle school students in an urban school community. While 73 percent of the students said they engage in leisure reading, 24 percent of leisure readers said they were consistent readers, and 49 percent said they read when they get a chance. Of the remaining 27 percent, 22 percent said they read only what they were assigned for school, and six percent said they did not read at all.

Other studies support the relationship between recreational/independent reading and academic achievement. Reis, et al. (2008) designed a study to examine the amount of time spent on recreational reading with intermediate elementary students to the positive affect of student achievement. The study found that when students were engaged in sustained independent reading they produced more favorable outcomes in reading fluency.

Focusing on empirical research with ESL learners, Wu Hui-Ju (2011) concluded that extensive reading positively affects ESL students’ comprehension and fluency performance as well as having a positive influence on students’ writing performance. Wu Hui-Ju suggests three strategies. With the first strategy, the students select reading material of interest that is within their reading ability level. After reading it, the students write a reaction report. In the second strategy, the teachers are role models and participate in independent reading with the students. The third strategy recommends that teachers frequently give feedback on students’ readings and interactions during the reading process.

Kinds of Recreational Reading

According to Krashen (2004) there are three kinds of in-school recreational reading programs: sustained silent reading (SSR), self-selected reading, and extensive reading. SSR is a time during which a class, teacher and, in some cases, the entire school reads for a designated amount of time during school hours. Students are allowed to choose their own reading materials, which include nonfiction or fiction books, magazines, or newspapers. Most SSR plans encourage students to continue reading out of school and permit students to change books when they lose interest. A great benefit to SSR is that it allows the teacher to model the habits, choices, and attitudes good readers develop (Gardiner, 2005; Krashen, 2004; Trelease, 2006).

During self-selected reading, free reading is a part of the language arts program, with teachers holding conferences to discuss students’ reading. Self-selected reading includes and usually begins with teacher read-alouds. The teacher reads to the students from a wide range of literature. Next, the students read silently from a variety of books related to the read-alouds’ topic or theme. While the children read, the teacher conferences with several students each day and records their progress. The students also maintain a folder to log pages read and give a brief daily summary (Atwell, 2007; Krashen, 2004; Trelease, 2006).

Extensive reading integrates a large number of self-selected print materials on a wide range of topics or themes. Material is at the students’ independent reading level, of interest to them, and they can read it more than once if so desired. The students periodically give short summaries of what they have read. The purpose of extensive reading is to seek pleasure, information, and general understanding. It also helps facilitate good reading habits and motivation for reading such as improving reading comprehension and improving writing abilities. Many ESL instructors use this approach (Bell, 2001; Day & Bamford, 1998; Krashen, 2004).

For many schools, SSR has been chosen to promote independent reading (Nichols, Rickelman, Young, & Rupley, 2008). Researchers, such as Bryan and Reutzel (2003), Krashen (2005), and Nichols, Rickelman, Young, and Rupley (2008) suggest that the primary purpose of SSR is to encourage students to read more and to increase their enjoyment of reading. McCracken (1971) developed and refined SSR into six basic guidelines that are still practiced today: (1) everyone reads self-selected materials silently, (2) teachers model by reading silently, (3) SSR takes place at the same time each day, (4) students select one piece of reading material for the entire time period and may not look for reading material during the SSR time period, (5) no assignments or records are kept, and (6) interruptions are not allowed.

Independent/recreational reading enables readers to select materials from various genres to read on their own. These should be materials that are highly interesting and motivating to the students. The goal of recreational/independent reading is pure enjoyment and to satisfy the desire to expand personal knowledge (Allington, 2006; Krashen, 2004; Miller, 2009; Lessesne, 2003; Taylor, Frye, & Maruyama, 1990).

Over the years, educators have attempted to incorporate into reading programs independent and recreational reading practices, strategies, activities, and incentives that spark and promote students’ interest and desire to read for pleasure (Block & Mangieri, 2002; Herald & Wiegand, 2006; Mangieri & Corboy, 1981; Pressley 2002; Schell, 1991). The rationale behind silent independent reading is that reading is a skill, and the more students practice, the better they become as readers. The simplicity of its format makes it easy to implement in any literacy program. Using an independent silent reading plan, the students and modeling teachers select their own reading materials and read silently at a regular time each day. Usually no work is assigned, students simply list the titles of books or reading material they read (Atwell, 2007; Block & Mangagieri, 2002; Fink & Samuals, 2007; Krashen, 2006; Mangieri & Corboy, 1981; McCracken, 1971; Trelease, 2006).

Bryan and Reutzel (2003) asserted that success of the independent silent reading approach depends on the teacher. The approach fails when teachers are supervising rather than modeling reading and the classroom is lacking reading materials (Bryan & Reutzel, 2003). According to Krashen (2005, 2008), a successful plan happens when students are reading to themselves for limited amounts of time.

Oral reading or read-aloud methods, directly or indirectly, help promote independent reading and affect recreational reading habits (McPhearson, 2008; Morrison & Wlodarczyk, 2009). In a teacher survey, Block and Mangieri (2002) found that teachers ranked reading to children daily as one of the most important methods to motivate students to read independently and for pleasure.

Other practices cited by researchers suggest increasing the amount of time spent in independent reading (Block & Mangieri, 2002; Bryan & Reutzel, 2003; Krashen 2004; Trelease, 2006). These practices include incorporating novels into content area lessons, sharing and discussing books read, replacing regular reading instruction with free reading trade books once a week, increasing parents’ knowledge of the importance of recreational reading, teachers’ modeling of the pleasure that they receive from reading pursuits, continuously making newly published books available to students, and exposing students to a wide variety of genres in classroom-based and school-wide libraries (Block & Mangieri, 2002; Schell, 1991; Trelease, 2006).

Researchers also endorse the use of technology to promote recreational and independent reading. There are a variety of ways to use technology in the classroom such as Accelerated Reader or Scholastic’s Reading Counts (Balajthy 2007). Another technological method is the Degree of Reading Power Book-link, which provides computer-based assistance for recreational reading. This program is designed to identify appropriate books for students with particular interests (Balajthy, 2007).

Technology is used to stimulate and enhance the independent readers’ desire to read more as well as to read more accurately. Rich sources of author and illustrator web sites as well as online bestsellers and children’s literature may enhance the love of recreational reading (Halverson and Smith, 2009).

eBooks are the latest reading technology tools that can motivate students to read independently and for pleasure. eBook users can download copies of a wide range of reading materials from websites, many public libraries, or purchase them from online bookstores.

There are other independent and recreational practices examined and endorsed that are worth mentioning. Individual reading choices are materials that students have independently chosen for recreational reading. Promoting development of ownership in reading helps students take full responsibility and possession of their reading process through the reading of materials they have chosen (Hooper, 2005; Mohr, 2006; Zeece, 2007). Collecting together reading material according to author, specific topic, or theme of reading has also been found to spark interest and encourage further independent and recreational reading (Atwell, 2007; Daniels, 2002; Hart, Burts, & Rosalind, 1997; Miller, 2002; Robinson, 2005: Sanacore, 2006).

Strategies for independent and recreational reading

Currently, there are three prominent strategies practiced in schools to help promote recreational reading: Literature Circles, Grand Conversations, and Book Talks. The goal of Literature Circles is to motivate students to read more through the enjoyment of social interaction in peer groups. In traditional Literature Circles, after a brief introduction from the teacher, students are divided into groups to read fiction or nonfiction books. Students are given roles or responsibilities that help guide their reading and meet on a regular basis to discuss agreed-upon sections of the book. The strategy ends with students presenting their book to their peers through presentations (Daniels, 2002). Researchers have examined the Literature Circle approach and have found that the strategy motivates students in free, independent reading time (Daniels, 2002; Sandmann & Gruhler, 2007). Students often feel an increased sense of responsibility toward their group and their own learning through the use of the various roles and discussions from the reading circle activity (Sandmann and Gruhler, 2007).

Grand Conversations are student-directed, whole class discussions. The strategy is different from other whole group discussions because it is completely student directed and typically focuses on a big question (Afflerbach, Pearson, & Scott, 2008). Research supports the assertion that a Grand Conversation expands comprehension of independent reading and encourages further silent reading (Afflerbach, Pearson, & Scott, 2008; Beeghly, 2005; Maloch, 2002; McKeown, Beck, & Blake, 2009).

Keeping students connected to books is critical for creating recreational and independent readers. One easy strategy to help motivate students to read is through book talks. A book talk, in its broadest definition, is an oral report or chat about a particular book with the purpose of sparking an interest in the listeners to read the book (Littlejohn, 2006). There is limited research conducted on the efficacy of book talks, but, according to Triplett and Buchanan (2005) they “continue to rouse minds and hearts to life” in public schools across the nation. Triplett and Buchanan (2005) conducted research with 14 first, second, and third grade struggling readers to identify strategies that engage students cognitively, motivationally, and emotionally. They concluded that book talks are an important aspect in promoting recreational reading.

Independent and recreational reading is an important aspect of a reading curriculum. It is essential that educators, including ESL instructors are up-to-date and informed of the various practices, strategies, research, and programs that support independent and recreational reading.

Bruce B. Brown, Ed.D., is a reading specialist and professor for Intensive Reading Education at Northern State University in Aberdeen, South Dakota. He received his Doctorate of Education degree with the University of South Dakota in 2011 and his Reading Specialist Masters Degree in 1991.

References

Afferback, P., Pearson, D., & Scott, G. P. (2008). Clarifying differences between Reading skills and reading strategies. The Reading Teacher, 61(5), 264-373.

Allington, R. L. (2006). Reading lessons and federal policymaking: An overview and introduction to the special issue, 107(1), 3-15.

Alsamadani, Hashem Ahmed (2011). The effects of the 3-2-1 reading strategy on EFL reading comprehension. English Language Teaching 4 (3), 184-191.

Amazon.com (2011). Kindle, world’s best selling E-reader. Retrieved from http://amazon.com/Kindle-e-Reader-eBook-Reader-e-Reader-Special-Offers/dp/BOOSIQVESA.

Atwell, N. (2007). The reading zone: How to help kids become skilled, passionate, habitual, critical readers. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Balajthy, E. (2007). Technology and current reading/literacy assessment strategies. Reading Teacher, 61 (3), 240-247.

Barnes & Noble.com (2011). Nook. Retrieved from http://www.barnesandnoble.com/nook/index.asp

Beeghly, D.G. (2005). It’s about time: Using electronic literature discussion groups with adult learners. Journal of Adolescent and Adult Literacy, 49(1), 1-13.

Bell, T. (2001) Extensive reading: Speed and comprehension. The Reading Matrix, 1(1), 1-13.

Block, C. C., & Mangieri, J. N. (2002). Recreational reading: 20 years later. The Reading Teacher, 55(6), 576-580.

Bryan, G., & Reutzel, D. R. (2003). Sustained silent reading: Exploring the value of literature discussion with three non-engaged readers. Reading Research and Instruction, 43(1), 47-73.

Carrell, P. (1989). Interactive approaches to second language reading. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1-3; 73-77.

Daniels, H. (2002). Literature circles: Voice and choice in book clubs and reading groups (2nd ed). Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Day, R. R., & Bamford, J. (1998). Extensive reading in the second language classroom. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Fink, R., & Samuels, S. J. (2007).Inspiring reading success. Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Gardiner, S. (2005). Building student literacy through sustained silent reading. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum.

Halverson, R., & Smith, A. (2009). How new technologies have (and have not) changed teaching and learning in schools. Journal of Computing in Teacher Education, 26(2), 49-54.

Hart, C. H., Burts, D. C., & Rosalind, D. (1997). Integrated curriculum and developmentally appropriate practice. Albany, New York: State University of New York.

Herald, D. T., & Wiegand, W. A. (2006). Genreflecting:A guide to popular reading interests (6th ed.) Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Hughes-Hassel, S., & Lutz, C. (2006). What do you want to tell us about Reading: A survey of the habits and attitudes of urban middle school students toward leisure reading. Young Adult Library Services, 42, 39-45.

Kelly, K., & Kneipp, L. B. (2009). You do what you are: The relationship between the scale of creative attributes and behavior and vocational interests. Journal of Instruction Psychology, 36(1), 79-83.

Krashen, S. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Westport, CT: Heinemann.

Krashen, S. (2005). Is in-school free reading good for children? Why the National Reading Panel is (still) wrong. Phi Delta Kappan, 86(6), 444-447.

Krashen, S. (2006). Free reading: Is it the only way to make kids more literate? School Library Journal, 52(9),42-45.

Krashen, S. (2008). Free voluntary reading: still a great idea. CEDE Yearbook, 1-11.

Lesesne, T. S. (2003). Making the match: The right book for the right reader at the right time, grades 4-12. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Maloch, B. (2002). Scaffolding student talk: One teacher’s role in literature discussion groups. Research Quarterly, 37(1), 94-113.

Mangieri, J., & Corboy, M. (1981). Quality reading programs-What are their ingredients? NASSP Bulletin, 65(449), 62-66.

McCraken, R. A. (1971). Initiating sustained silent reading. Journal of Reading, 14(8), 521-524.

McKeown, M. G. Beck, I. L., & Blake, R. G. K. (2009). Rethinking reading comprehension instruction: A comparison of instruction for strategies and content approaches. Reading Research Quarterly, 44(3), 218-253.

McKool, S. S. (2007). Factors that influence the decision to read: An investigation of fifth grade students’ out-of school reading habits. Reading Improvement, 44(3), 111-131. Reading Improvement, 44 (3), 111-131.

McPherson, K. (2008). Reading lifelong literacy links into the school library. Teacher Librarian, 36(1), 72-74.

Miller, D. (2009). The Book Whisper: Awakening the inner reader in every child. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Mohr, K. J. (2006). Children’s choices for recreational reading: A three-part investigation of selection preferences, rationales, and processes. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(1), 81-104.

Morrison, V., & Wlodarczyk, L. (2009). Revisiting read-aloud: Instructional strategies that encourage students’ engagement with text. The Reading Teacher, 63(2), 110-118.

Nichols, W. D., Rickelman, R. J., Young, C. A., & Rupley, W. H. (2008). Understanding and applying reading instructional strategies: Implications for professional development in the middle schools. College Reading Association Yearbook, 23, 220-236.

Pressley, M. (2002). Reading instruction that works: The case for balanced teaching. New York, NY: Guilford.

Reis, S. M., Eckert, R. D., McCoach, D. B. Jacobs, J. K., & Coyne, M. (2008). Using enrichment reading practices to increase reading fluency, comprehension, and attitudes. Educational Psychology, 101(5), 299-315.

Robinson, R. D. (2005). Readings in reading instruction: Its history, theory, and development. New York, NY: Pearson Education, Inc.

Sanacore, J. (2006). Nurturing lifetime readers (Electronic version). Childhood Education, 73(3), 157-161.

Sandmann, A. E., & Gruhler, D. (2007). Reading is thinking: Connecting readers to text through literature circles. The International Journal of Learning, 13(10), 105-113.

Schell, L. (1991). How to create an independent reading program. New York, NY: Scholastic Professional Books.

Taylor, B. M., Frye, B. J., & Maruyama, G. M. (1990). Time spent reading and reading growth. American Educational Research Journal, 27(2), 352-362.

Trelease, J. (2006). The read-aloud handbook. New York, NY: Penguin Books.

Triplett, C. F., & Buchanan, A. (2005). Book talk: Continuing to rouse minds and hearts to life. Reading Horizons, 46(2), 63-75.

WU Hui-ju. (2011). An innovative teaching approach for decreasing anxiety and enhancing performance in L2 reading and writing. Sino-US English Teaching, 8 (6), 357-363.

Zeece, P. D. (2007). The best thing about a book is… Early Childhood Education Journal, 34(5), 345-350.

India’s New Education Policy, which is currently being formulated, will give Hindi its “due status,” according to the country’s minister for human resource development, Satyapal Singh.

India’s New Education Policy, which is currently being formulated, will give Hindi its “due status,” according to the country’s minister for human resource development, Satyapal Singh.

Swahili (Kiswahili) has become the first African language to be recognized by Twitter. The network now recognizes Swahili words and offers translation of the widely spoken and written East and southern African language. However, it has still not been added to the language settings of Twitter.

Swahili (Kiswahili) has become the first African language to be recognized by Twitter. The network now recognizes Swahili words and offers translation of the widely spoken and written East and southern African language. However, it has still not been added to the language settings of Twitter.

Bruce B. Brown examines how independent reading can transform the oute to English language acquisition

Bruce B. Brown examines how independent reading can transform the oute to English language acquisition

Actor and writer Fred Armisen, known for T.V. series “Portlandia”, is creating a new Spanish-Language comedy, “Los Espookys,” on HBO. Armisen will be a co-writer and executive producer for the show, and will also appear in the role of Tico. Ana Fabrega and Julio Torres will co-write the series, set in a surreal version of present-day Mexico City. The show will star Bernardo Velasco, Cassandra Ciangherotti, Fabrega, Torres, and Armisen. The show will follow a set of friends, turning their love for horror into a peculiar business.”

Actor and writer Fred Armisen, known for T.V. series “Portlandia”, is creating a new Spanish-Language comedy, “Los Espookys,” on HBO. Armisen will be a co-writer and executive producer for the show, and will also appear in the role of Tico. Ana Fabrega and Julio Torres will co-write the series, set in a surreal version of present-day Mexico City. The show will star Bernardo Velasco, Cassandra Ciangherotti, Fabrega, Torres, and Armisen. The show will follow a set of friends, turning their love for horror into a peculiar business.” For over 800 years, Finnish has been Sweden’s largest minority language, but, thanks to the recent influx of asylum seekers from predominantly Arab-speaking countries in the Middle East and North Africa, Arabic has now replaced Finnish, Stockholm University researcher Mikael Parkvall argued in an opinion piece published in

For over 800 years, Finnish has been Sweden’s largest minority language, but, thanks to the recent influx of asylum seekers from predominantly Arab-speaking countries in the Middle East and North Africa, Arabic has now replaced Finnish, Stockholm University researcher Mikael Parkvall argued in an opinion piece published in  According to the

According to the  California’s superintendent of public instruction, Tom Torlakson, has launched Global California 2030, which is a call to action “to vastly expand the teaching and learning of world languages and the number of students proficient in more than one language over the next twelve years.”

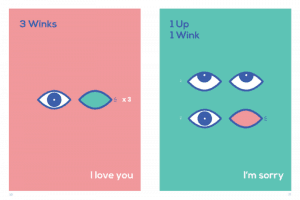

California’s superintendent of public instruction, Tom Torlakson, has launched Global California 2030, which is a call to action “to vastly expand the teaching and learning of world languages and the number of students proficient in more than one language over the next twelve years.” A new language called Blink to Speak aims to improve the lives of people with paralysis and have difficulty with speech, and recently won the Health Grand Prix for Good at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The guide outlines a new language that uses eye movements for communication for people with paralysis. The language was created by Dr. Hemangi Sane, Founder and President of Asha Ek Hope Foundation and Deputy Director of DueirGen Brain and Spine Institute in Mumbai, India.

A new language called Blink to Speak aims to improve the lives of people with paralysis and have difficulty with speech, and recently won the Health Grand Prix for Good at the Cannes Lions International Festival of Creativity. The guide outlines a new language that uses eye movements for communication for people with paralysis. The language was created by Dr. Hemangi Sane, Founder and President of Asha Ek Hope Foundation and Deputy Director of DueirGen Brain and Spine Institute in Mumbai, India.