One day at recess, a distraught five-year-old approached me and proclaimed angrily, “Fulanito me tagó.” Confused, I attempted to understand her meaning: “¿Te tocó?” (“He touched you?”) She shook her head. “¿Te atacó?” (“He attacked you?”). No again, thankfully. Frustrated, the student replied, “Me taGÓ, like in tag, Maestra.”

In that moment, I realized I had only been activating half of my linguistic repertoire, while my student had been leveraging all of hers, converting the English verb tag into a grammatically correct “Spanglish” phrase to express her outrage that a classmate had tagged her in the playground game. In this moment of clarity, I began to wonder about the real risks for my students if they were never exposed to the benefits of translanguaging as a resource for their language and literacy learning.

In this reflection, Aubrey reveals a tension that many dual-language educators face when planning for language in their classrooms. On the one hand, teachers are tasked with upholding the program’s language allocation polices, which generally endorse strict language separation as a means to “protect” the minoritized language.

On the other hand, teachers recognize that their emergent bilingual students exhibit a range of dynamic bilingual languaging practices not often represented in classroom instruction. Thus, many are left wondering: Can a bilingual classroom embrace more flexible language practices while still privileging the minoritized language? And, if so, what would such practices look like?

We—two teachers and one teacher educator—have grappled with these questions and, in response, have developed a framework for designing and integrating more flexible language pedagogies into the bilingual classroom.

Our approach is framed around Ofelia García’s (2009) notion of translanguaging, a term that highlights the dynamic languaging practices of bilingual students. A translanguaging perspective maintains that bilingualism is not the “full” mastery of two or more individual (separate) languages. Instead, bilingualism is understood as dynamic, with translanguaging as the authentic way that bilingual individuals, families, and communities communicate (Baker and Wright, 2017). Translanguaging theory also posits that languages are not separated in the mind of the bilingual person; rather, the bilingual mind is seen as a holistic system that contains diverse linguistic resources, employed as needed for different communicative purposes.

Guiding Principles

If we take this holistic understanding of bilingualism to be true, then it is vital that bilingual educators consider ways of moving beyond the binaries of language separation to leverage students’ entire linguistic repertoires. With this goal in mind, here is the PIE framework, a set of three guiding principles to support teachers in designing and implementing translanguaging pedagogies in their classrooms

Translanguaging Pedagogy in the Bilingual Classroom

Principle 1: Translanguaging pedagogies should be purposefully designed and implemented.

Perhaps the most important component is the purposeful design of flexible language practices. As with any instructional design, educators seeking to incorporate

translanguaging pedagogies must consider the goals of the lesson and how the structure of the languaging environment will support student learning.

While emergent bilingual students (and teachers) often spontaneously engage in flexible languaging in the classroom, translanguaging pedagogies should be purposeful and strategic, designed to support student learning and metalinguistic awareness. Importantly, we are not advocating for the removal of “focused” language spaces, in which students engage exclusively (or mostly) in the target language; however, we contend that “flexible” language spaces are equally valuable, provided they are purposefully designed (Hamman, 2018).

Principle 2: Translanguaging pedagogies should promote interaction and inclusion, drawing upon what students know individually and collectively.

The second principle is ensuring that the dynamic languaging space promotes student interaction and is inclusive of all learners. This principle is grounded in a sociocultural understanding of learning (Vygotsky, 1978), which posits that meaning-making is enhanced when students can actively engage in learning with their peers.

We contend that linguistic knowledge, like content knowledge, is distributed across all students in the classroom such that learning is enhanced when students work collaboratively and leverage their full (shared) linguistic repertoire. Bilingual classrooms provide a rich setting for dialogic translanguaging, as all students are learning in two (or more) languages and can bring their varied linguistic expertise to bear on collective learning activities.

Principle 3: Translanguaging pedagogies should enrich learning across all of the languages in a student’s repertoire.

Translanguaging pedagogies should also be understood as enriching learning across all of the languages in a student’s repertoire, creating spaces for students to make connections across languages and deepening student understanding of content knowledge. Jim Cummins (1979, 1981) posited that a bilingual’s languages are interdependent, such that knowledge and skills learned in one language can transfer to the other, provided the necessary conditions for language learning. Translanguaging pedagogies can help to facilitate this transfer, activating the interdependency among a student’s different linguistic resources and enabling students to flexibly negotiate meaning and develop deeper metalinguistic knowledge.

Translanguaging for Literacy Learning

Here are two examples of translanguaging pedagogies designed to support literacy learning in the bilingual classroom, written by classroom teachers to share their experiences with designing translanguaging pedagogies.

Aubrey: Collaborative Translanguaging in an Interactive Read-Aloud

Since my students develop initial literacy in both English and Spanish, I designed a translanguaging activity that would enable students to use all of their linguistic resources to collectively narrate a story. I selected the text Yes by Jez Alborough, a picture book with few words and very detailed illustrations. It illustrates a bedtime routine, a familiar activity for all of my students. Although the story is in English, the goal was for students to co-construct the story using all of their (collective) linguistic resources.

I explained: “This book is in English, but has very few words, so I need everyone’s help to tell what is happening in the story.” As the goal of the activity was to provide space for students to actively contribute to the storytelling process, I let students offer ideas without raising their hands or waiting to be called on, while also asking specific questions to students I knew were less likely to shout out an answer. The story begins as Bobo, the young monkey, and his mother begin his bedtime routine with a bath. The first text in the story appears in a speech bubble as Bobo’s mother tells him, “Bath time, Bobo” (see Figure 2).

Rather than solicit student translations, I asked, “¿Pueden decirlo de otra manera?” (“Can you say it in another way?”). This framing of the question provided a more flexible space for students to share their ideas in English, Spanish, or both. My students took on the translanguaging task with gusto, eagerly offering up ideas one after another: “Hora de bañarse, Bobo.” “Vamos a bañarnos, Bobo.” “Time for your bath.”

On the next page, Bobo is happily taking a bath in the pond, saying simply, “yes, yes, yes.” “Bobo is splashing and laughing,” one child remarked. “Está jugando en el agua” (“He is playing in the water”), another added. I asked the class, “¿Cómo se siente Bobo ahora?” (“How does Bobo feel?”). A chorus of “¡Féliz!” rang out. “¿Pueden decirlo de otra manera?” I inquired, and a couple of students shared, “He is happy.” As this was a literacy lesson, I also wanted to engage my students in making inferences, so I asked them how they knew that Bobo was happy. “Bobo está feliz porqué está jugando en el agua” (“Bobo is happy because he is playing in the water”), one student commented. Another replied, “He is smiling,” referencing a detail in the illustration. As the story continued, I asked students to make personal connections to the text. “¿A quién le gusta bañarse cómo Bobo? (“Who likes bath time as much as Bobo?”) A sea of excited hands went up. “Me gusta jugar en el agua” (“I like to play in the water”), one child exclaimed. “I don’t take baths anymore. I like the shower,” another remarked, as more students began to chime in with their experiences.

Throughout the activity, my students were excited and engaged in the dynamic languaging task of telling a story through multiple languages. I had strategically planned my prompts for each page of the book in order to elicit the most student responses and variety of language use. My questions were open-ended: “How does Bobo feel?” “What do you see now?” “What do you think will happen next?” “Have you ever felt like Bobo?” This approach, coupled with the flexible space for bilingual

languaging, provided multiple entry points for student engagement and promoted active participation as students developed foundational concepts of literacy, such as making inferences and sequencing. As my students were unhindered by language separation rules, I was able to more easily point out similarities and differences between the two languages. This simple yet rich learning activity provided a space for my emergent bilingual students to leverage their full linguistic repertoires, supporting the development of important literacy skills and enriching their learning experience.

Emeline: Joint Construction of a Bilingual Informational Text

Third grade is the first year in which students receive formal literacy instruction in English. My students are expected not only to learn new content and develop as writers but also to become competent English writers, which can be a daunting task. I designed this translanguaging activity as a way to explicitly “bridge” students’ developing competencies in English and Spanish and to build upon their existing writing skills. As part of a thematic unit, students had been studying ecosystems. They were tasked with writing a bilingual informational text about one of the ecosystems that they had researched. For authenticity, I told them that they would share these informational texts with their parents, so it was important that the texts be bilingual for all families to understand them.

Due to the complex nature of the task, I paired each student with a collaborative writing partner for the duration of the project. Students began by researching their chosen ecosystems. They were provided with graphic organizers as well as online resources (in English and Spanish) that contained information on different ecosystems. Once students had gathered enough information, they began writing the texts with their collaborative writing partners. They were instructed to alternate the languages they used to write the different sections of their texts, in order to provide students with targeted practice in each of the instructional languages.

For example, students wrote about animals and plants in their ecosystem in English and then wrote about the location of their ecosystem in Spanish. As they worked, I circulated and encouraged them to use both of their languages. I, too, modeled flexible bilingualism, fluidly switching between languages or using one language to process content in the other.

After students finished writing, it was time to translate each section to create a fully bilingual text. Knowing that my students would have different levels of familiarity with translating, I began by talking with them about their experiences with translation. Many students shared that they translated for their parents or siblings. This discussion helped validate students’ everyday translating practices and established translation as a valuable skill. I also modeled the difference between word-for-word translation and translating for meaning.

With these understandings, students began self-translating their informational texts with their collaborative writing partners. As they worked, I took note of common errors and planned a series of mini-lessons to address common areas of difficulty such as subject-verb agreement.

Self-translation proved to be incredibly powerful, not only as a way to validate students’ lived bilingualism but also as a tool for students to build metalinguistic awareness and strengthen their writing in both languages. To illustrate this point, I will share that a pair of Spanish-dominant students improved their writing through the two-way process of translation and revision.

The students’ initial paragraph was written in English and discussed the food chain in the tundra ecosystem: “The bunny eats the beris then the fox eats the bunny, the wolf eats the fox. Then when the wolf is dead the bacteria breaks down to the soil.”

While there is some reflection of Spanish phonetics in the spelling of “beris,” the words in the paragraph are otherwise spelled correctly and follow a logical sequence. Then, as students self-translated their work into Spanish, they wrote:

El conejo come las bayas. Luego el zorro se come al conejo. Después viene el lobo y se come al zorro. Finalmente, el lobo se muere y la bacteria lo rompe y se lo lleva a la tierra.

[The bunny eats the berries. Then the fox eats the bunny. After the wolf comes and eats the fox. Finally the wolf dies and the bacteria breaks it down and brings it to the soil.]

While the students maintained the same content in their Spanish translation, their writing became more sophisticated. They incorporated more punctuation, perhaps owing to a better sense of the natural pauses in the Spanish writing.

The students also added sequence adverbs to transition between sentences, such as después (“then”) and finalmente (“finally”), which were not included in the initial text in English. Finally, in the last sentence, students included the third-person direct-object pronoun lo to refer to el lobo (“the wolf”), a pronoun whose translation (“it”) was absent in the English paragraph: “when the wolf is dead the bacteria breaks [it] down to the soil.”

Translation and Revision as a Two-Way Process

After the students had translated their writing in English to Spanish, they returned to the English text for revisions. As a result, their final English text was enhanced, as the students incorporated the structural and grammatical elements that had been included in the Spanish text. The final text read: “The bunny eats the beris. Then the fox eats the bunny. After the wolf eats the fox. Finally when the wolf dies the bacteria breaks it down and brings it back to the soil.” Thus, the two-way translation and revision process, within a space that enabled students to utilize their full linguistic repertoire, strengthened students’ writing and enriched their second-language learning.

Applying the PIE Framework

Is it purposeful?

Both Aubrey and Emeline were intentional and strategic in their design of translanguaging pedagogies. Aubrey selected a text with a topic that would be familiar to all of her kindergarten students and thoughtfully crafted questions for each page that would promote student engagement and activate their full linguistic repertoires. Her decision to reframe the question “Can you say this in Spanish?” to “Can you say it in another way?” opened up a more fluid space that both enabled students to make cross-linguistic connections as they translated the text and created opportunities for richer connection-making as students engaged in the collaborative co-construction of the story.

Emeline was also purposeful in her design of the third-grade writing unit. Like Aubrey, she ensured that students would have sufficient background knowledge about the topic before they began the complex task of writing bilingually. Students were strategically paired so that they had peer support in both research and writing, which was especially helpful when students began self-translation of their texts. Emeline designed mini-lessons to prepare students for new skills (such as translation) and in response to common areas of difficulty. The unit was framed around an authentic purpose: presenting the informational texts to their parents.

As a result, students were invested (Norton, 2000) in developing the necessary language and content knowledge.

Is it interactive and inclusive?

In the design of the read-aloud as co-constructed bilingual storytelling, Aubrey created an interactive space where all students were able to participate and all aspects of students’ linguistic repertoires were validated. By allowing students to share without raising their hands, Aubrey fostered idea-building and productive talk; at the same time, by thoughtfully calling upon students who had not yet shared, she ensured that students who were less comfortable with the free-flow sharing environment would still have an opportunity to contribute.

Emeline also ensured that her unit would foster interaction and inclusion. Students created a joint informational text with their collaborative writing partners, which led to active negotiation of meaning as students created the original text and then translated it into English and Spanish. Some scholars have found that translanguaging can support individual students in planning, drafting, and producing a text (Velasco and Garcia, 2014). Emeline extends this work by demonstrating how an interactive approach to translanguaging in writing opens up spaces for students to develop new understandings as they engage in collaborative self-revision.

Is it enriching?

In Aubrey’s interactive read-aloud, students were able to generate a range of ideas and inferences that would have likely been limited if storytelling had been constrained to one language. As students made connections to the story, they shared in Spanish (“Me gusta jugar en el agua.”) and in English (“I don’t take baths anymore. I like the shower.”). Aubrey leveraged the translanguaging space to point out similarities and differences across languages, which may not have occurred had the text been read in English. Translanguaging, therefore, enabled more idea-generation, as students could share in any language(s), and created opportunities for cross-linguistic comparisons, as both the teacher and the students became more attentive to the ways that the two languages were related.

Emeline’s unit also provides clear evidence of the enriching power of translanguaging pedagogies, most notably in her example of two-way revision. She demonstrates, convincingly, that the collaborative bilingual writing process created a space for positive cross-linguistic transfer, what Gort (2006) refers to as positive literacy application—students applying literacy skills from one language to another. As Emeline’s students had more experience with Spanish writing and were Spanish-dominant speakers, it was perhaps no surprise that their Spanish text was more sophisticated. However, had students not been given the opportunity to translate their English text into Spanish and then engage in two-way revision, it is unlikely that they would have applied their literacy skills from Spanish to improve their English text. The flexible languaging space enabled students to create more sophisticated texts in both languages and enriched their literacy learning as a whole.

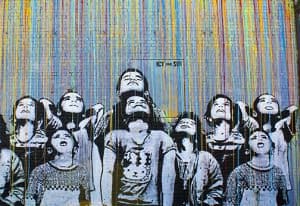

These examples demonstrate the importance of leveraging translanguaging as a pedagogical resource in the bilingual classroom and provide some constructive guidelines for teachers to begin to re-envision their classrooms as translanguaging spaces, spaces for translanguaging created by translanguaging (Li, 2011). Translanguaging pedagogies should be purposefully designed, interactive, and inclusive and enrich students’ entire linguistic repertoires. They support students in making metalinguistic connections and in leveraging all of their content and linguistic knowledge. However, beyond the academic and linguistic benefits, translanguaging in the classroom is also an important way to validate who students are and what they bring to the classroom. No student should have to “leave themselves at the door” or feel that part of who they are is not welcome at school. Translanguaging pedagogies enable students to bring their whole selves into the classroom and help us all to become learners, as we navigate new linguistic terrains with our students as our guides.

References

Baker, C., and Wright, W. (2017). Foundations of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Cummins, J. (1979). “Linguistic Interdependence and the Educational Development of Bilingual Children.” Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222–251.

Cummins, J. (1981). “The Role of Primary Language Development in Promoting Educational Success for Language Minority Students.” In California State Department of Education (ed.), Schooling and Language Minority Students: A Theoretical Framework. Los Angeles: Evaluation, Dissemination and Assessment Center, California State University, 3–49.

García, O. (2009). Bilingual Education in the 21st Century: A Global Perspective. Malden: Wiley/Blackwell.

Gort, M. (2006). “Strategic Codeswitching, Interliteracy, and Other Phenomena of Emergent Bilingual Writing: Lessons from first-grade dual language classrooms.” Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 6(3), 323–354.

Hamman, L. (2018). “Translanguaging and Positioning in Two-Way Dual Language Classrooms: A case for criticality.” Language and Education, 32(1), 21–42.

Li, W. (2011). “Moment Analysis and Translanguaging Space: Discursive construction of identities by multilingual Chinese youth in Britain.” Journal of Pragmatics, 43(5), 1222–1235.

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and Language Learning: Gender, Ethnicity and Educational Change. Harlow, UK: Pearson Education/Longman.

Velasco, P., and García, O. (2014). “Translanguaging and the Writing of Bilingual Learners.” Bilingual Research Journal, 37(1).

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: The Development of Higher Psychological Processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dr. Laura Hamman is an educational researcher at the University of Colorado-Boulder and an instructor/specialist with the English as a New Language program at the University of Notre Dame.

Emeline Beck is a bilingual teacher in Madison, WI. She studied Spanish and Elementary Education and received a Master’s in ESL/Bilingual Education from UW-Madison.

Aubrey Donaldson has taught emergent bilingual children in the U.S. and Guatemala. She studied Elementary Education and Spanish at UW-Madison and completed a Masters in ESL/Bilingual Education in 2015.

Inquiring Scientists, Inquiring Readers in Middle School: Using Nonfiction to Promote Science Literacy couples the Common Core Standards of middle school science with the multimodal aspects of literacy (e.g., reading, writing, speaking, viewing, and listening). Shiverdecker and Fries-Gaither have developed a convenient handbook for those instructors who wish to transform their middle school science lectures into integrative engagements wherein students are prompted to think differently. Shiverdecker and Fries-Gaither begin by describing the format of the text in addition to explaining how the text should be used. The text is separated into two segments. Part I, “Integrating Science and Literacy Instruction,” serves as a how-to for first-time users. Here, the authors demonstrate how and why literacy can be integrated into middle school curriculum.

Inquiring Scientists, Inquiring Readers in Middle School: Using Nonfiction to Promote Science Literacy couples the Common Core Standards of middle school science with the multimodal aspects of literacy (e.g., reading, writing, speaking, viewing, and listening). Shiverdecker and Fries-Gaither have developed a convenient handbook for those instructors who wish to transform their middle school science lectures into integrative engagements wherein students are prompted to think differently. Shiverdecker and Fries-Gaither begin by describing the format of the text in addition to explaining how the text should be used. The text is separated into two segments. Part I, “Integrating Science and Literacy Instruction,” serves as a how-to for first-time users. Here, the authors demonstrate how and why literacy can be integrated into middle school curriculum. Starting Strong is a practical resource for preservice instructors and experienced professionals of early-development classrooms looking for ways to more effectively build foundational literacy skills. As an easy-to-navigate compilation of research-based strategies and the theoretical foundations that support them, it is designed to be adapted for various classroom settings: whole groups, small groups, play-based centers, independent practices, etc. The authors also acknowledge an imperative to provide resources especially for instructors of struggling readers and of children living in poverty, and Starting Strong’s utility certainly extends to providing strategies for instructors of multilingual classrooms. Four bases of instruction serve as the rationale for the suggested strategies—illustrating how Starting Strong is based on the realities of many teachers’ situations. For example, the authors cite Common Core in order to discuss how state standards can contextualize classroom practices in a meaningful way. They also discuss how evidence-based techniques save instructors time by avoiding experimentation with classroom strategies that do not have a strong record of making instruction more effective. Finally, the authors’ choice to construct the book around student-based instruction is a primary example of why the book works. Thus, Starting Strong is written for instructors who know (or want to know) their students and want to find ways to use researched techniques to work for their readers.

Starting Strong is a practical resource for preservice instructors and experienced professionals of early-development classrooms looking for ways to more effectively build foundational literacy skills. As an easy-to-navigate compilation of research-based strategies and the theoretical foundations that support them, it is designed to be adapted for various classroom settings: whole groups, small groups, play-based centers, independent practices, etc. The authors also acknowledge an imperative to provide resources especially for instructors of struggling readers and of children living in poverty, and Starting Strong’s utility certainly extends to providing strategies for instructors of multilingual classrooms. Four bases of instruction serve as the rationale for the suggested strategies—illustrating how Starting Strong is based on the realities of many teachers’ situations. For example, the authors cite Common Core in order to discuss how state standards can contextualize classroom practices in a meaningful way. They also discuss how evidence-based techniques save instructors time by avoiding experimentation with classroom strategies that do not have a strong record of making instruction more effective. Finally, the authors’ choice to construct the book around student-based instruction is a primary example of why the book works. Thus, Starting Strong is written for instructors who know (or want to know) their students and want to find ways to use researched techniques to work for their readers. Indigenous languages are a core part of both

Indigenous languages are a core part of both

Sobrato Philanthropies, funded through the real estate successes of the Sobrato family in Silicon Valley, has developed an innovative pre-K to third-grade capacity-building program for teachers to address the needs of English learner (EL) students, specifically Latino ELs. The Sobrato Early Academic Language (SEAL) model is a replicable model of professional development and program design aligned with Common Core standards that helps students to attain age-appropriate literacy in both English and their home languages (wherever possible) and a grade-level mastery of academic material—becoming more motivated, confident learners by the end of third grade.

Sobrato Philanthropies, funded through the real estate successes of the Sobrato family in Silicon Valley, has developed an innovative pre-K to third-grade capacity-building program for teachers to address the needs of English learner (EL) students, specifically Latino ELs. The Sobrato Early Academic Language (SEAL) model is a replicable model of professional development and program design aligned with Common Core standards that helps students to attain age-appropriate literacy in both English and their home languages (wherever possible) and a grade-level mastery of academic material—becoming more motivated, confident learners by the end of third grade.

Over the last year or so, the movement against high-stakes standardized testing has subsided, maybe due to educational activists focusing their attention on more pressing issues, such as funding, in the Trump era, or maybe because the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) creates the possibility for states to shift the focus of accountability from punishment of schools and teachers to policies that genuinely help improve educational quality and equity. However, even with enormous improvements to testing regimes across the U.S. and the availability of a much wider range of assessment methods, standardized tests are still being used to the detriment of English language learners and other minorities.

Over the last year or so, the movement against high-stakes standardized testing has subsided, maybe due to educational activists focusing their attention on more pressing issues, such as funding, in the Trump era, or maybe because the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) creates the possibility for states to shift the focus of accountability from punishment of schools and teachers to policies that genuinely help improve educational quality and equity. However, even with enormous improvements to testing regimes across the U.S. and the availability of a much wider range of assessment methods, standardized tests are still being used to the detriment of English language learners and other minorities. Katie Nielson asks if online collaboration may sabotage language learning

Katie Nielson asks if online collaboration may sabotage language learning The United Nations has declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IY2019) to help preserve indigenous languages and safeguard the rights of those who speak them. According to the IY2019 website,

The United Nations has declared 2019 the International Year of Indigenous Languages (IY2019) to help preserve indigenous languages and safeguard the rights of those who speak them. According to the IY2019 website, This article introduces the H5P website—an innovative, free, practical, and easy-to-use tech software that English teachers and students can use when engaged in teaching and learning English.

This article introduces the H5P website—an innovative, free, practical, and easy-to-use tech software that English teachers and students can use when engaged in teaching and learning English.