Terrie L. Noland believes we need to understand the automaticity of executing lower-level reading processes in order to master higher-level comprehension

Terrie L. Noland believes we need to understand the automaticity of executing lower-level reading processes in order to master higher-level comprehension

Automaticity is necessary in everything we do to enable us to move to higher-order thinking skills and perform tasks flawlessly.

When we first learn to drive a car, we expend our brainpower on technical skills such as speed, turn signals, and road signs. We use both hands on the steering wheel. It takes significant cognitive capacity to remember to look in the mirrors to change lanes. At this stage of our learning process, we have not mastered the “automaticity” of the skills needed to drive a car, but with practice and confidence, our lower-level processing becomes automatic as we drive.

Reading for Meaning—Multifaceted Reading Definitions

This is true in the classroom. If we cannot easily perform lower-level reading processes like phonemic awareness, phonics, and decoding with automaticity, we will find it more difficult to free up our mental capacity to concentrate on the task.

When our cognitive load becomes too intense to comprehend, there is more likelihood that gaps in our learning process will exist and thus affect reading achievement and give us a feeling of failure.

This scenario happens for a great many English learners, as well as learners who are socioeconomically disadvantaged, struggling readers, and students with learning disabilities, like dyslexia.

Research suggests that the act of reading is multifaceted:

1) An explicit skill-building activity necessary to access print.

2) An ability to comprehend text that comes from accurate word decoding.

While researchers debate the definition of finite reading skills such as fluency (Rasinski et al., 2011), there is a consensus that reading does involve understanding written text and constructing meaning from that text (Afflerbach et al., 2011).

What happens if teachers only pay attention to one reading definition? Let’s test this.

Reading Test

Read the following excerpt from Diary of a Wimpy Kid, a popular series for ages 7–13, with a Lexile level of 950:

“Today is the first day of school, and right now we’re just waiting around for the teacher to hurry up and finish the seating chart. So I figured I might as well write in this book to pass the time. By the way, let me give you some good advice. On the first day of school, you got to be real careful where you sit. You walk into the classroom and just plunk your stuff down on any old desk and the next thing you know the teacher is saying—‘I hope you all like where you’re sitting, because these are your permanent seats’”(Kinney, 2007).

If you have mastered the skills of decoding and fluency, pulling words from the page by attaching sounds to letters and reading with correct rate (automaticity and prosody), then you are likely to make sense of the text. Your brain met the automaticity of the lower-level processes (Kendeou, 2014).

Now, read the following excerpt from a medical journal about developmental dyslexia:

“Two female subjects showed multiple instances of focal myelinated conical infraction, with neuronal loss, gliosis, and myelination of the scars affecting perisylvian and cerebral arterial border-zone territories. The presence of myelin in the scars suggested that the injury preceded the second or third year of postnatal life.

One of the males showed, in addition to microdysgenesis, a small number of these myelinated scars. The brain of the 20-year-old female had no scars in the cortex but did have a small number of ectopias distributed equally between the hemispheres. Other abnormalities included a bilobar hippocampal oligondendraglioma and a frontal arteriovenous anomaly in one female case; one male and another female case also showed arteriovenous anomalies and a male showed arthitectonic abnormalities in the lateralis posterior and medial geniculate nuclei of the thalamus” (Galaburda et al., 1985, p. 223).

Did you exhaust brainpower to decode all the technical words in this text? Did it slow you down? Did you try context clues or isolating root words and affixes to decipher the vocabulary? Did you feel less smart when you read the second passage compared to the first?

Cognitive Load Theory

This is an example of cognitive load theory, suggesting that our working memory can only handle two or three pieces of infor

mation at a time. The limitations of working memory overload the finite skills of full comprehension (Rueda, 2011; Foorman et al., 2011). Cunningham et al. (2011) stated, “when word recognition is not yet automatized, the reader experiences significant cognitive demands while decoding text. As a reader matures, and the demands of conceptually more difficult texts require the use of complex thinking strategies, a reduction in conscious attention is necessary at the word recognition level to free up cognitive energy required for comprehension” (p. 260). During the time from reading the first passage to the second, your intelligence did not change. What changed was your ability to decode content and understand what you read. In the second passage, our brainpower had to drive into overload to use our lower-level processes.

Bridge the Automaticity Reading Gap—Fluency

“Reading fluency helps to reduce the cognitive demand and thus makes text comprehension easier for the reader” (Rueda, 2011).

Dr. Maryanne Wolf (2008), in her book Proust and the Squid, builds a visual story of what reading is about by uncovering the precepts of reading as defined by Marcel Proust: “Proust saw reading as a kind of intellectual sanctuary, where human beings have access to thousands of realities they might never encounter or understand otherwise” (p. 6).

We need to help struggling readers and those with learning disabilities find a bridge to content while they are still learning the lower-level processes of reading. Many educators use an evidence-based structured literacy program, but this approach takes time, maybe one or two years.

Just as any young child can comprehend above his or her ability to read, so can a student who is struggling to read. These students require a tool to help them automatize the decoding process and to provide reinforcement of skill building in the lower-level processes of reading. Access to human-read audiobooks can serve as a reliable tool to keep both processes going simultaneously—comprehension and cognition.

Holistic Reading Approach

If we only allow students to rely on the explicit skills they are taught, their ability to catch up to grade level will be farther out of reach. As a community of researchers and education professionals, we must consider three questions:

Are the cognitive capacities and abilities of students, not just learning-disabled students, on par with grade-level content when the lower-level processes of reading are not automatized?

What are the tools and resources that teachers use to create a holistic environment and culture of reading and literacy when time and pacing of curriculum do not allow adequate time spent on explicit instruction?

Are classrooms that take a more holistic approach to reading instruction more effective?

With further investigation into these questions and applying recommended tools such as human-read audiobooks, we can hope that the achievement gap will lessen over a shorter period of time and students who struggle with the finite processes of reading can keep pace with their peers.

Resources available at https://www.languagemagazine.com/decoding-versus-cognitive-ability-resources/

Terrie Noland serves as the VP of Educator Initiatives for Learning Ally where she works to develop engagement programs, professional learning services and communities for educators. She has more than 25 years of experience as both a motivational leader and developer of content, and is certified as an Academic Language Practitioner.

The amount of the minimum income protection in Austria is now to be made dependent on the German language skills, among other factors, according to reports from Vienna.

The amount of the minimum income protection in Austria is now to be made dependent on the German language skills, among other factors, according to reports from Vienna.

Manuela Gonzalez-Bueno introduces a

Manuela Gonzalez-Bueno introduces a The U.S. House and Senate have both introduced bills that encourage the replacement of math, science, and foreign language courses with computer coding in high schools.

The U.S. House and Senate have both introduced bills that encourage the replacement of math, science, and foreign language courses with computer coding in high schools.

Terrie L. Noland

Terrie L. Noland Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have created a tool called a “semantic parser” that mimics the experience of children learning a language. The semantic parses does what children typically do—observe their environments and listen to speakers, regardless of if they actually understand what the speakers are saying or not. The system observes captioned videos and associates the words that speakers say with recorded objects and actions.

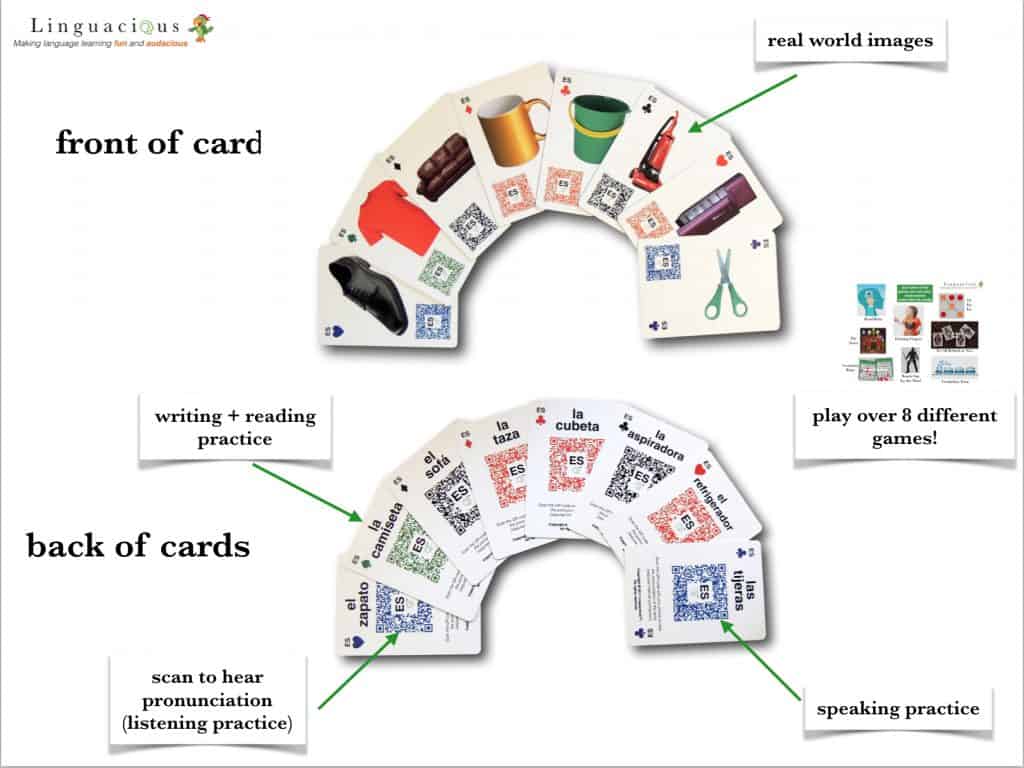

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have created a tool called a “semantic parser” that mimics the experience of children learning a language. The semantic parses does what children typically do—observe their environments and listen to speakers, regardless of if they actually understand what the speakers are saying or not. The system observes captioned videos and associates the words that speakers say with recorded objects and actions. According to a new report by Zion Market Research, the global language learning games market, which was valued at about $377 million last year, is expected to be worth $2.45 billion by 2026.

According to a new report by Zion Market Research, the global language learning games market, which was valued at about $377 million last year, is expected to be worth $2.45 billion by 2026. AB

AB Research into the neurological activity required to switch between languages is providing new insights into the nature of bilingualism.

Research into the neurological activity required to switch between languages is providing new insights into the nature of bilingualism. The Reaching English Learners Act has been introduced in Congress in hopes of creating a solution to the national shortage of ELL teachers. The act would create a grant program under Title II of the Higher Education Act.

The Reaching English Learners Act has been introduced in Congress in hopes of creating a solution to the national shortage of ELL teachers. The act would create a grant program under Title II of the Higher Education Act.