Classroom teacher: “That kid from Africa. He’s suspended again. He is always bothering everyone at lunch in the cafeteria.”

TESOL teacher: “What country is he from?”

Classroom teacher: “I don’t know? Africa. He is just defiant and disrespectful.”

TESOL teacher: “What language does he speak?”

Classroom teacher: “I don’t know. Congolonian?”

TESOL teacher: “Ummmmm. That’s not a language. The student is from Sierra Leone. He speaks Yoruba as his first language and is nearly proficient in English. It can be considered disrespectful to look you directly in the eyes as an elder. Also, his school experience did not include gathering in a cafeteria for meals. Being in a large room, waiting in line for a meal, and then sitting with peers to socialize is a new cultural construct for him. How can we help him to do this?”

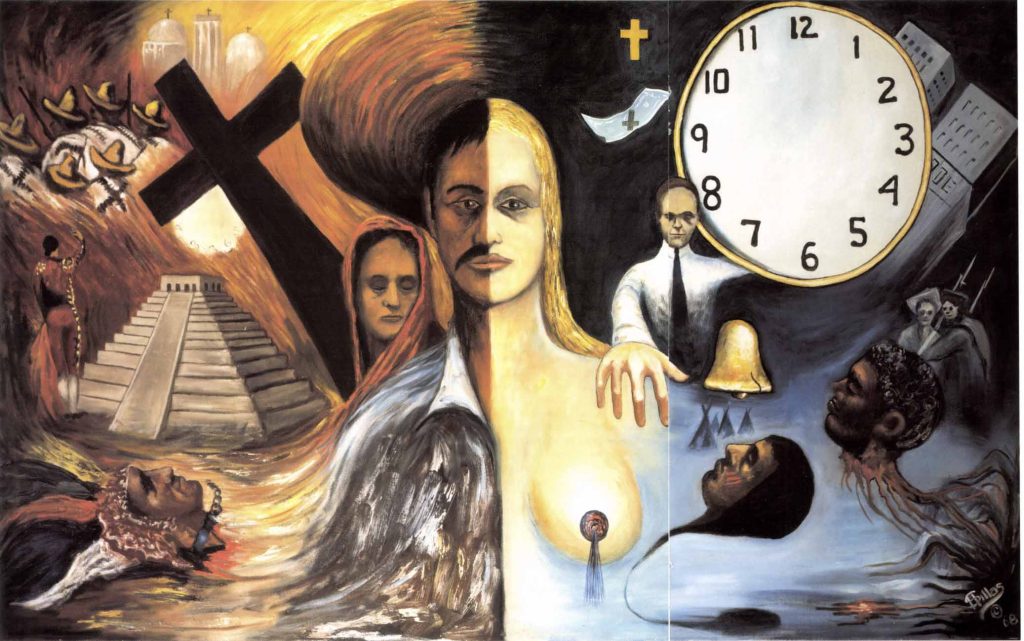

Me—I am that TESOL teacher. This conversation—one of many conversations I have as a teacher of middle school multilingual learners and new arrivals that without fail raise my hackles and force me to choose my response on the fly, to know without wavering who I am and what I believe. Right from wrong. Do I uphold the bias with my silence, or do I find my voice to ameliorate the constructs of nescience that serve as barriers to every student with Black skin that enters my classroom?

The prickly hackles, seemingly always on end, are a response to covert racism (Coates, 2012), “nice” racism (Coates, 2012), linguicism, colorism… the -isms of other, different, unfamiliar, implicit hate, bias, ignorance, tilted systems. An alphabet soup of ugly -isms. We swam in them day after day. Until one day, over lunch, as my colleague and I lamented on the daily complaints we receive about the multilingual students and new arrivals, we recognized the pattern.

Our students from Haiti, Sierra Leone, Congo, Ghana, the West Indies, Jamaica— our Black students—they are the ones persistently on the lower end of the grading scale. They are reported to us by other teachers as the students who “just won’t do anything in class,” “just don’t get it,” and perpetually have a pile of work to catch up on. “Ms. B, here is the list of assignments so-and-so needs to finish from [insert content area].”

What do you do when, day after day, the racial, linguistic, cultural, and social obstacles are piled up against students by the very educators whose job it is to break down the barriers and lift all students to achieve? How do a White girl from Upstate New York and a Haitian immigrant nontenured instructor speak out about the blatant if covert racism that serves as an invisible mesh in our collaborative praxis? Without agency (and with unreliable tenure), we were just two teachers with a hunch.

While our students seemingly continued to take up residence on the daily discipline and suspension rosters, we saw what we needed. The data. Regardless of anecdotal hunches, assumptions, and lunchtime conversations, we needed numbers. But what data—and how to get it?

When I entered the state data hub, I could see Hispanic students’ and White students’ language scores. I could not see Black multilingual learner students’ data. Perhaps the ɳ was under a set number and there were not enough students in single locations to be counted? We thought this could not be the case because in our district, we had enough Haitian Creole newcomer students to initiate a federally mandated bilingual center. And, beyond our small state, a recent infographic from OELA told us that in cities such as St. Cloud, Minnesota, more than 50% of English learners identify as Black. And in Lewiston, Maine, 72% of the English learner roster is students of African descent.

We called the State Department of Education’s Performance Office to request achievement data for students who identify as both Black and English learner. This intersection is not part of the current algorithm my state uses for monitoring students. In our quest, my superintendent received a phone call from the head of the performance division to ask why I was looking for this data, as it had not ever been requested before.

The obstacles faced in obtaining performance data for Black English learners, although varied and detailed, simply told us that no one is counting this subgroup of students. They have not been seen. We know there is a way to count our Black English learners, and now there is a standing request to do so. There is now an expectation that we count and monitor the achievement of our Black English learners. Perhaps this is the first positive outcome of the hunch we had.

Unquestionably, Black students who are multilingual learners need to be seen, included, and supported. Just ask Lourdjinia Louis1 or Sekuye Bolende2 or Arden Amber Desormeau.3 A good read about the importance of this is Awad El Karim M. Ibrahim’s ethnographic study “Becoming Black: Rap and Hip-Hop, Race, Gender, Identity, and the Politics of ESL Learning.”4

Ibrahim digs into how being Black affects English learning, especially for refugee African youths in a Canadian high school. These students, seen as Black by society, end up identifying with Black America, picking up Black stylized English from hip-hop and rap. His study emphasizes that language learning isn’t straightforward—it’s loaded with the politics of race, social acceptance, and linguicism.

Cooper and Ibrahim also published a collection of essays, Black Immigrants in the United States: Essays on the Politics of Race, Language, and Voice (2020), in an effort to bring more attention to the Black student experience.

In education, we speak of equity, inclusion, and diversity for all. When large-scale data is collected on all students, but we cannot see some students, is that equity? I think not. Last year, I had the opportunity to see civil rights icon Kimberlé Crenshaw speak at the Courageous Conversation summit in Washington, DC.5 In her work, intersectionality acknowledges that people’s lives are shaped by a complex interplay of factors such as race, gender, class, sexuality, and more. In the role of TESOL teacher, that “more” includes language.

Race, language, and culture create a unique experience for new arrivals of African descent especially. A New America blog post by Leslie Villegas and Efren Velazco in April 2021 discusses this significance, stating that “many students who belong to the EL group experience issues of racism, discrimination, and xenophobia in the education system, including Latinx and Asian students.

For Black ELs, however, issues of language, culture, and race can be harder to separate which means we cannot equitably meet their needs without addressing anti-Blackness that reverberates through our education system.”6

Educators’ roles are critical in whether barriers are built or removed for Black immigrant students who are multilingual English learners. We can create a collaborative partnership for the achievement of our students or a praxis mired with deficit thinking and bias, both implicit and explicit. Regardless, Black students who are multilingual learners need to be seen.

What can a teacher do? As Dr. Ayanna Cooper once said to me, and I have taken liberty to paraphrase, “Say it. Say the words. Racial diversity. Anti-Blackness. It is important to say the words, or diversity forgets racial diversity and racism forgets our Black English learners.”

Put on a lens for anti-Blackness and organize your questions into three categories:

• Policy—How is data collected? Who is counted? What languaging is used in policy? Who is prioritized?

• Profession—Are Black ELT professionals at the table? Who is represented by organizations such as CEA, NTL, and TESOL? Whom are TESOL MA programs marketed to?

• Practice and programming—How does anti-Blackness show up in the systems and structures of programming and in your organization? Do Black ELs see themselves in curriculum materials and in instructional practices?

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.” –Bayard Rustin, American civil rights activist

I am okay with making trouble if it means all of our students have what they need to bypass and break through the limiting -isms that stand in the way of achievement and success. And I believe that all teachers who see any -ism can have the agency to create systemic change. Just say the words and ask the questions.

Links

1. www.boston.com/news/the-boston-globe/2023/07/17/madison-park-valedictorian-lourdjinia-louis

2. www.greencardvoices.org/speakers/sekuye-bolende

3. www.instagram.com/reel/CsWAZT1q-a4/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

4. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.2307/3587669

5. https://courageousconversation.com

6. www.newamerica.org/education-policy/edcentral/looking-beyond-the-typical-english-learner-the-intersectionality-of-black-english-learners-in-us-public-schools

References

Coates, R. D., and Morrison, J. (2011). Covert Racism: Theories, Institutions, and Experiences. Studies in Critical Social Sciences, vol. 32. Brill.

Comrie, J. W., Landor, A. M., Riley, K. T., and Williamson, J. D. (2016). “Anti-Blackness/Colorism.” Boston University Center for Antiracist Research. www.bu.edu/antiracism-center/files/2022/06/Anti-Black.pdf

DiAngelo, R. (2022). Nice Racism: How Progressive White People Perpetuate Racial Harm. Penguin Books.

Larcarte, V. (2022). “Black Immigrants in the United States Face Hurdles, but Outcomes Vary by City.” Migration Policy Institute. www.migrationpolicy.org/article/black-immigrants-united-states-hurdles-outcomes-top-cities

Singleton, G. E. (2022). Courageous Conversations about Race: A Field Guide for Achieving Equity in Schools and Beyond. Corwin.

Jill Bessette is a multilingual learner education specialist at LEARN in Connecticut. She is a veteran educator of 25 years and is completing her doctorate in TESOL at Anaheim University. Jill is an adjutant instructor at the University of St. Joseph in Hartford, Connecticut.