In a midsized school, a veteran second-grade teacher is working diligently with her students on a unit called Taking Shape. An aspect of Irene’s teacher craft that she values is getting to know her students, how their linguistic and cultural resources can enrich the class, and what fosters their learning. Additionally, during planning time, Irene and her grade-level team pay special attention to academic language use to construct a multishaped model, the product of the unit.

The group of teachers carefully selects relevant college and career readiness standards and matches them to English language development standards to ensure that English language learners (ELLs) have as many opportunities to access the content, engage in learning, and achieve academically as their English-proficient peers. In designing curriculum, the standards, the instructional materials, and the funds of knowledge from the families and community are major sources of academic language in classrooms. Using these resources, the team sets learning targets that focus on the major concepts and highlight academic language.

What is academic language and why is it important?

In today’s classrooms, with the prominence of challenging content standards, rigorous academic content is at the center of teaching. Academic language, the language required by students to understand and communicate that understanding in subject-area disciplines, forms the heart of grade-level curriculum, instruction, and assessment (Gottlieb and Ernst-Slavit, 2014). Academic language (also referred to as scientific language, critical language, and the language of school) helps define the pathways to school success. It is the language of textbooks and homework, in classrooms, and on tests. It is different in register, structure, and vocabulary from everyday speech and social interactions.

Educational theorists and linguists offer varying definitions and a variety of perspectives on what constitutes academic language use. The following bulleted list is a brief summary of some of the major contributors to the discussion; see which views are most aligned to your own, your grade-level team’s, and your school’s philosophy.

- We construct meaning from the purpose of the communication and its related language choices.

- We process and produce language around particular functions or purposes that are expressed through vocabulary, grammatical forms, and discourse.

- We have come to realize that literacy as meaning making extends beyond text to include discourses from visual arts, digital input, and other forms of multimedia.

- We use language to understand multiple points of view and perspectives as members of communities of practice.

- We attribute academic success to cognitive engagement, language skills, and metalinguistic strategies.

- We recognize that students’ identities and student agency are central to deep and involved learning where they are active participants.

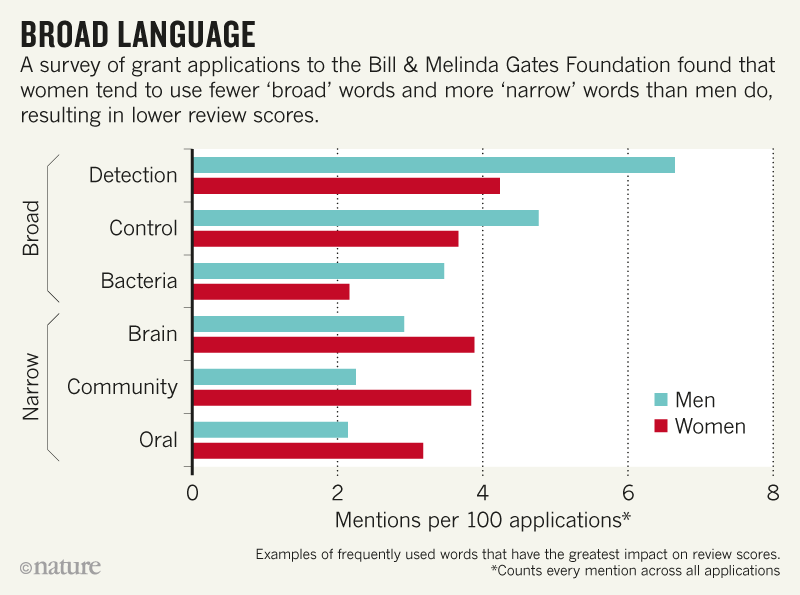

Although there are different representations of academic language use, most everyone agrees on its three dimensions. As shown in the diagram below, discourse, exemplified by different genres or text types, shapes the organization and structure of sentences, which in turn consist of vocabulary, expressed as general, specialized, and technical words and expressions.

The Dimensions of Academic Language

Academic language use is central to today’s content classrooms. Because academic language conveys the abstract and complex ideas of the disciplines, it allows users to think and act, for example, as scientists, historians, and mathematicians. “Learning academic language is not learning new words to do the same thing that one could have done with other words; it is learning to do new things with language and acquiring new tools for these purposes” (Nagy and Townsend, 2012, p. 93).

Academic language is much more than vocabulary. Knowledge of single words is not enough to describe complex concepts, thinking processes, and abstract ideas and relationships. The academic language needed by students to access grade-level content and successfully participate in activities and assessments involves knowledge and ability to use specific linguistic features associated with academic disciplines. As shown in the figure, these features include discourse elements, grammatical constructions of

sentences, and vocabulary that often represents multiple meanings across language domains (listening, speaking, reading, writing) and content areas.

Each content area or discipline has a unique discourse, sentence structure, and vocabulary. Think about it. There is a prescribed way of formulating the language used to solve a geometric theorem, and that discourse is distinct from how to narrate a fairy tale, debate the issue of space exploration, or compare two historical events. Providing a deep and well-planned foundation of academic language that considers its multiple dimensions allows students to reach disciplinary success.

The dimensions of academic language help characterize content. Here are some examples of discourses, sentences, and vocabulary for each content area. Embedding the dimensions of academic language into content teaching enables students to attend to processing and producing oral and written text. Let’s look at some classrooms where students are busily using academic language as part of deep and meaningful interactions that revolve around disciplinary practices and activities.

How is academic language learned in different classrooms?

A Fifth-Grade Example

In a fifth-grade classroom in a southeastern state, Maria and her 24 students are embarking on an interdisciplinary unit on ocean ecology with strong ties to literature. Like many teachers, Maria has a diverse group of students, including seven ELLs, in addition to other students with home languages that include English, Spanish, Gujarati, Arabic, Russian, Tamil, and Bosnian.

Maria is excited about this unit, because she and the other fifth-grade teachers plan to adopt the city aquarium as a teaching tool. Together with her grade-level colleagues, Maria selects the essential knowledge and skills along with the corresponding academic language for this ecology unit, which she applies to crafting content targets for science and language arts. Maria then combs the state’s English language development standards to create a language target for the unit. Here are her overall content and language expectations.

Maria uses a picture walk and small-group brainstorming to grab students’ interest in the different organisms found in marine ecologies. She nurtures that interest by having students point out the many exotic and colorful fish species that live in tropical environments, some of which the students are familiar with. As students look at the maps around the classroom, they note that some of their peers have written their names on regions where they have lived or visited. Maria knows that making connections for her students makes learning more motivating and meaningful.

The ecology unit is packed with a variety of engaging tasks, with assessment that is integrated into instruction. Maria is a strong supporter of oral interaction between and among students. She facilitates students working in pairs, in small groups, or in large groups and provides opportunities for students to develop their oral language to access grade-level content. By setting up criteria for success with her students, she is able to make ongoing focused observations and offer students descriptive feedback. Students also have time to reflect on their learning, using the same criteria, and engage in peer assessment. Here are some of Maria’s ideas used during this unit.

An Eighth-Grade Example

Now on to a middle school English language arts class, where Enrique and his eighth- grade students are engaged in dissecting the academic language of gothic literature. Enrique has decided to focus on Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Cask of Amontillado.” Taking into account the content or college and career readiness standards and language development standards, the materials for the unit, and the strengths of his students, Enrique plunges into the unit.

There are many other instances in which the teacher builds on the students’ linguistic repertoires and capitalizes on their interests. One specific example of making connections with the students’ languages and cultures is having them compare a written gothic story (“The Cask of Amontillado”) and an oral gothic story from Latin America (“El Chupacabra,” or “The Goat Sucker”) known by many of the students. The comparison centers on the devices used in each story that contribute to unity of effect, such as setting, symbols, foreshadowing, mood, and tone.

At the close of the unit, students are able to articulate the features and characteristics of gothic stories, including those from other languages and cultures, and to relate Edgar Allan Poe’s tales of mystery and the macabre to contemporary novels, movies, and oral traditions from Latin America. Enrique is pleased that his class can articulate the meaning and give examples of allegory and symbolism in both written and oral gothic stories using grade-level academic language (Minaya-Rowe, 2014).

Academic language: Important for all, essential for ELLs

For several decades now, academic language has been important to the work of educators engaged in advancing educational equity for ELLs. With the emergence of college and career readiness standards, academic language learning has become equated with the educational success of all students. Academic language can no longer be considered the “top ten” important words needed for a topic or lesson. Rather, academic language needs to be broadly understood as the knowledge and ability to use specific linguistic features (dimensions of discourse, sentences, and vocabulary) within the context of the content-area practices. This kind of language affords ELLs, alongside their English-proficient peers, opportunities to think, know, act, and interact during instruction. Ultimately, academic language offers pathways for all students to maximize their success in school.

References

Gottlieb, M., and Ernst-Slavit, G. (2014). Academic language in Diverse Classrooms: Promoting content and language learning: Definitions and contexts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

McCloskey, M. L., and New Levine, L. (2014). In M. Gottlieb and G. Ernst-Slavit (series eds.). Academic Language in Diverse Classrooms: Promoting content and language learning, English language arts, grades 3–5, (pp. 131–178). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Minaya-Rowe, L. (2014). “A Gothic Story: ‘The Cask of Amontillado.’” In M. Gottlieb and G. (series eds.). Academic Language in Diverse Classrooms: Promoting content and language learning. English language arts, grades 6–8, (pp. 137–182). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

Nagy, W. and Townsend, D. (2012). “Words as Tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition.” Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 91–108.

This article originally appeared in Language Magazine in September, 2016. Dr. Margo Gottlieb was co-founder and lead developer of WIDA at the Wisconsin Center of Education Research, University of Wisconsin-Madison and Dr. Gisela Ernst-Slavit was professor of education and ELL at Washington State University in Vancouver. Margo and Gisela authored a foundational book and co-edited a series of language arts and mathematics books on academic language in diverse classrooms, published by Corwin.