The Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre has launched a series of four immersive apps produced in the Digital Innovation Hub the center has established with the funding. Designed to preserve the Pilbara region’s Indigenous languages, culture, and history, the apps communicate traditional stories and knowledge with a unique Indigenous perspective.

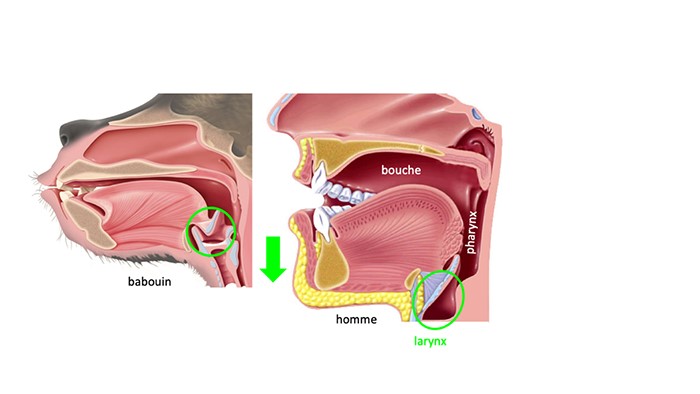

The app technology brings language and culture to life through authentic storytelling, original audio, supportive linguistic tools, evocative imagery, interactive features that include the ability to record oneself, and animation that makes the emu run and the dingo howl. The launch of the new apps demonstrates the center’s success in establishing the Innovation Hub, approved as a Commonwealth Grant in 2018. In the past 16 months, the center has set up infrastructure, appointed a senior linguist, developed protocols and plans, gained an app developer license, and learned how to use technology to communicate the Indigenous worldview.

The establishment has been supported by New Zealand Indigenous technology company Kiwa Digital. Speaking at the launch of the new apps at the 2019 International Year of Indigenous Languages Expo in Roebourne, center manager Julie Walker said: “Our digital project is making a vital contribution to the revitalization of Pilbara languages.

The goal is to bring the expertise, knowledge, and sensitivity of the elders of the Pilbara into the digital age.” Kiwa Digital CEO Steven Renata praised the center on its rapid take-up of new technology: “Pilbara languages are on a rapid path to digitization, with the Centre leading the way globally in adopting new techniques to convey unique Indigenous perspectives.”

The apps are available on the App Store and Google Play by searching for WANGKA MAYA.

New App Releases

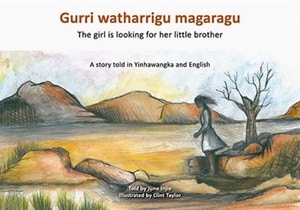

Gurri Watharrigu Magaragu The Girl Is Looking for Her Little Brother

This app by author June Injie tells the story of a young girl who goes looking all over for her little brother. This story is told in the Yinhawangka language with English translation. Yinhawangka is a severely endangered language from the Pilbara region of Western Australia. The Yinhawangka people traditionally lived in the area containing the Angelo, Ashburton, and Hardey Rivers, Kunderong Range, Mount Vernon Station, Rocklea, and Turee Creek. There are currently a limited number of people who speak Yinhawangka. The app is a valuable contribution to the revitalization of Yinhawangka language and culture.

Thanamarra Ngananha Malgu What Are They Doing?

The app contains an engaging story about the habits of some animals, both native and introduced, that can be found in the Pilbara region. The story demonstrates the keen observation of animal behavior by the Yinhawangka storyteller, as expressed in her rich and concise language. This story is told in the Yinhawangka language with English translation. Yinhawangka is a severely endangered language from the Pilbara region. The Yinhawangka people traditionally lived in the area containing the Angelo, Ashburton, and Hardey Rivers, Kunderong Range, Mount Vernon Station, Rocklea, and Turee Creek.

Pilurnpaya Ngurrinu They Found a Bird

This children’s story with audio was told to Martu teacher Janelle Booth by children from Jigalong. It features Martu Wangka and English readings of the story, plus coloring-in images and extensive notes on the linguistic details on the Martu Wangka language. Martu Wangka, or Wangkatjunga (Wangkajunga), is a variety of the Western Desert language that emerged during the 20th century in Western Australia as several Indigenous communities shifted from their respective territories to form a single community. It is spoken in the vicinity of Christmas Creek and Fitzroy Crossing.

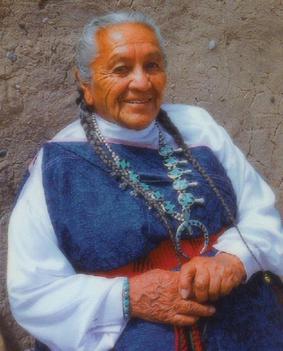

Kathleentharndu Wanggangarli Kathleen’s Stories

The stories in this app were first recorded in 2009 by Banyjima elder Kathleen Hubert with the help of linguist Eleanora Deak. Kathleen created the stories for her children and grandchildren, to help keep their language skills strong. The stories were originally published as five separate booklets and made available to Kathleen’s family. In 2014 Kathleen generously gave the Wangka Maya Pilbara Aboriginal Language Centre permission to publish the stories and make them available to the wider community.

This second edition was compiled by Annie Edwards-Cameron as part of the 2014 IBN Language Project.

Many thanks are due to Kathleen’s daughters May Byrne and Karen Hubert and granddaughter Dolly for their permission to reproduce their photos in these stories.

Kiwa Digital works with Indigenous groups around the world, using technology to preserve ancestral knowledge in formats that are relevant and accessible. For more, see www.kiwadigital.com.

The Wangka Maya Language Centre manages programs aimed at the recording, analysis, and preservation of the Pilbara region’s Indigenous languages, culture, and history. There are more than 31 Aboriginal cultural groups in the Pilbara and over 3,000 speakers. For more, see www.wangkamaya.org.au.