When we have a chance to look back, many in education will recognize 2020 as the year that learning radically changed. The impact of quickly pivoting the entire industry to an online environment has only begun to truly sink in. It is clear technology will play a role in learning in more conscious and thoughtful ways for the foreseeable future. As the fall approaches and we look toward a blended, hybrid, digital future, the focus on working with technology has made it easy to forget one critical area of support for future success: our ability to manage the social and emotional needs of both our learners and ourselves.

Self-Management and Social-Emotional Learning

Social and emotional learning (SEL) has become an important dimension of the so-called soft skills, or life skills, valuable for long-term success both in learning and careers. SEL is often used to describe the specific aspects of self-management that help people work through various conflicts, challenges, and crises. Being able to manage oneself, one’s emotional response, and one’s ability to navigate the social and emotional responses of others is an important life skill necessary for setting and achieving goals.

Learners’ demonstrations of self-management skills are good predictors of strong academic performance (Duckworth and Seligman, 2005), especially when learners are capable of self-regulating the desire for instant results by regulating their own needs for gratification. While self-management alone does not fully encompass all of the social and emotional skills learners engage, the abilities associated with strong self-management are also regularly highlighted as necessary study skills and attitudes. Further, these skills are good indicators of college or university success (Credé and Kuncel, 2008). They include:

• Time management

• Resource management

• Knowledge monitoring

• Stress management

• Anxiety management

• Persistence

Supporting the development of strong self-management skills helps learners perform consistently in an academic environment. When developed, self-management skills can improve interpersonal interactions, raise feelings of security, manage emotional responses, and help students meet challenges with higher self-esteem while reducing risky behaviors, like binge eating and drinking (Tangney, 2004). SEL skills are also extremely important to employers; 80% of employers describe social and emotional management as important factors in career success (Durlak et al., 2011).

As we quickly approach the end of the summer season and prepare to return to our various schools and institutions, understanding and applying SEL strategies is just as important as embracing technology, and for some learners it may be the key factor in their academic success this year and beyond.

The Five Core Competencies of SEL

The Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning (CASEL) provides a useful framework for understanding the core competencies of SEL, which are defined as:

• Self-awareness

• Self-management

• Social awareness

• Relationship skills

• Responsible decision making

The skills that underpin the SEL competencies can be observed when learners demonstrate the following:

• Planning—setting realistic goals and planning activities ahead of time

• Organization—keeping work artifacts in an organized fashion to improve efficiency

• Persistence—applying appropriate levels of effort to tasks, in spite of obstacles or difficulty

• Progress monitoring—accurately tracking and assessing one’s knowledge, skills, and progress; choosing appropriate strategies to evaluate and improve knowledge, skills, and progress

• Control—effectively regulating behaviors and emotions, typically to support goal pursuit

• Attention to detail—having careful, precise habits; ensuring work products are accurate, clear, and precise (Yarbro and Ventura, 2018)

Understanding and observing these skills are particularly useful to language educators who want to incorporate SEL support into the overall learning experience. For the language teacher, supporting SEL can be particularly challenging, especially when the skills and language necessary to communicate social and emotional needs in English are still developing. As educators, we must help to bridge the communication gap and allow learners to express their real-life concerns through the language they are working actively to develop. Recognizing the indicators of successful application of SEL competencies is key to knowing how language learners manage their current academic lives and social challenges. Further, educators can support the development of activities at an appropriate language level to help students manage themselves and communicate their needs when appropriate.

SEL Activities for English Language Learners

To address the SEL needs of English language learners, we must both understand the emotional needs that require support and provide tangible activities at an appropriate level of language challenge for learners. Ideally, SEL activities should take advantage of students’ abilities and offer opportunities to use language they have mastery over. However, some aspects of SEL support will introduce new language and concepts to learners, so it is helpful to account for language difficulty in order to ensure that supporting students’ social and emotional needs reduces stress rather than creating it.

The following activities are designed for specific language levels (Council of Europe, 2001; de Jong, Mayor, and Hayes, 2016); however, all could be adapted, with more or less scaffolding as appropriate (Davila, 2017).

Using Lists and Graphic Organizers

Can write very short, simple sentences about their feelings. Writing, 32, A2 (30–35)

Can tell a story or describe something in a simple list of points. Speaking, 42, A2+ (36–42)

When addressing self-management, begin by acknowledging the emotional needs of your learners. Have students reflect on what anxiety they are feeling and describe the emotions they feel. Make a list of four physical symptoms they associate with feelings of anxiety.

For each symptom on the list, discuss a behavior that can be used to manage the emotion and anxiety, such as:

• Breathing exercises

• Taking a moment for focused exercise

• Counting to or backward from a number

Once during each session, allow time for discussion and encourage students to refer to their lists or bullet points to describe their personal anxiety symptoms. Create a collaborative resource where learners can share their specific symptoms. Include short, simple descriptions of specific behaviors they personally employ to help reduce anxiety and emotional stress.

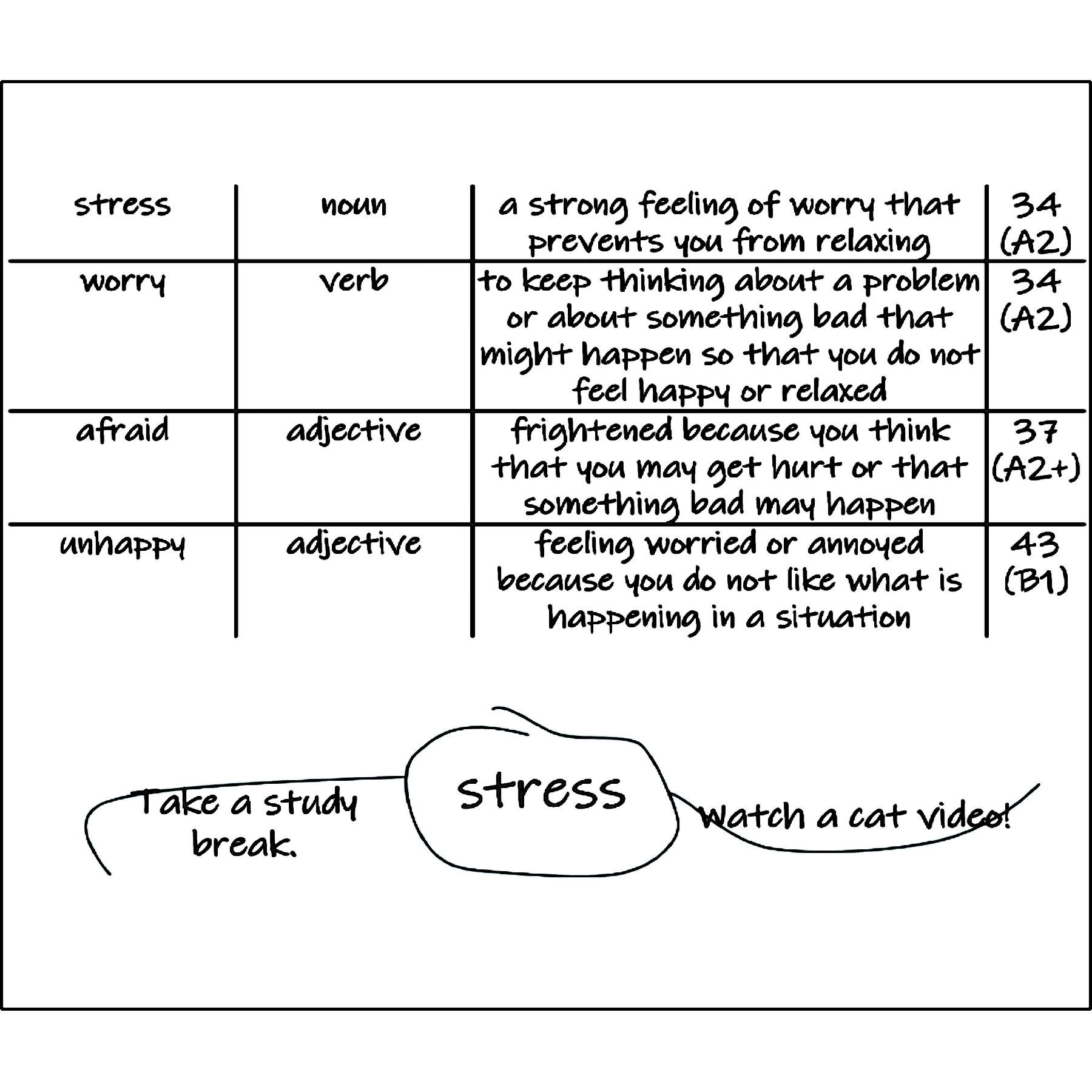

Help ensure that language is not a barrier for learners by introducing vocabulary to let students describe their personal experiences. Additionally, mind maps and other graphic organizers can be used instead of lists to help students make strong connections between emotional feelings and behaviors to self-manage.

Encourage students who are working remotely to use notebooks and share pictures through online platforms. In hybrid situations, classroom learners can connect in real time with learners in different locations and use video calling to show or display work in real time.

Use Reflection Journals

Can write descriptions of past events, activities, or personal experiences. Writing, 47, B1 (43–50)

Can ask and answer questions about past times and past activities. Speaking 40, A2+ (36–42)

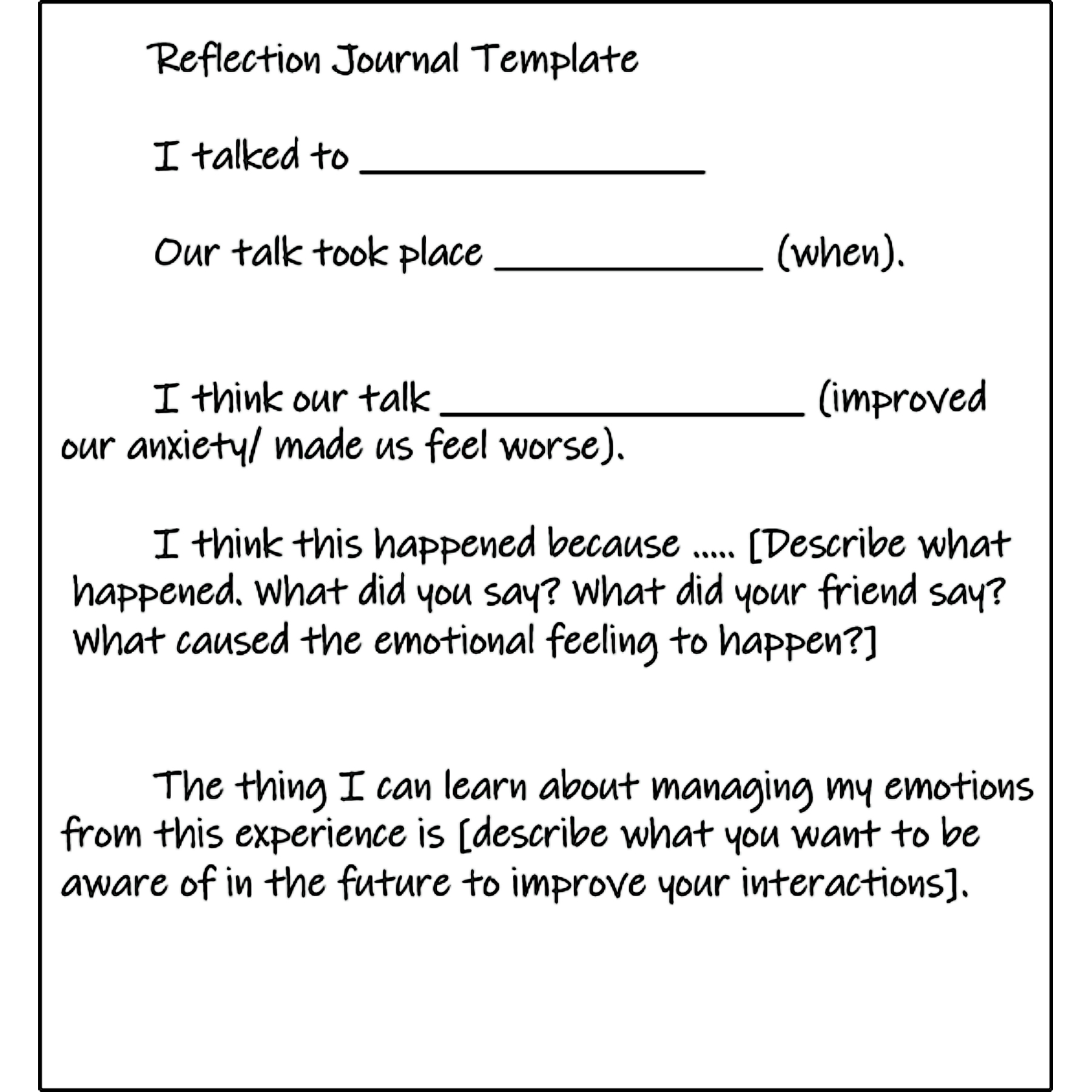

Reflective journals can be useful for developing self-awareness, as well as improving social awareness and understanding relationships with others. Have students think of a specific interaction with someone from that day or week and describe the interaction. For this exercise, learners may describe classmates, co-workers, or family members.

Ask learners to describe all aspects of the interaction, including their emotions and those of others they engaged with. Did others have positive or negative responses in these interactions? Note what actions could be taken in the future to strengthen positive and reduce negative interactions.

Further scaffold this activity by using a journal template. These reflective journals do not need to be shared with the larger class. In class, schedule a consistent time, daily, weekly, or monthly, in which to review especially challenging moments, the types of emotions involved, and the overall results. Examine the cause and effect of certain interactions. Use this information to plan for how to respond and engage in future interactions with the same people or to address similar challenges.

Using Online Groups and Projects to Support SEL

Can introduce themselves and manage simple exchanges online, asking and answering questions and exchanging ideas on predictable everyday topics, provided enough time is allowed to formulate responses and that they interact with one interlocutor at a time. Online Communication, 42, A2+ (36–42)

Can post online accounts of social events, experiences, and activities referring to embedded links and media and sharing personal feelings. Online Communication, 57, B1+ (51–58)

Supporting SEL with language learners can also be incorporated as a regular part of communication in various learning environments. Where an entire program is online, SEL discussions can be regularly planned events, so learners know they are coming and have time to consider what social or emotional challenges they want to discuss with others. Also, a forum, chat, or group can be designated exclusively for discussions related to social and emotional challenges. Consider hosting this space with options for learners to post in both English and their native languages, to provide maximum opportunities for engagement.

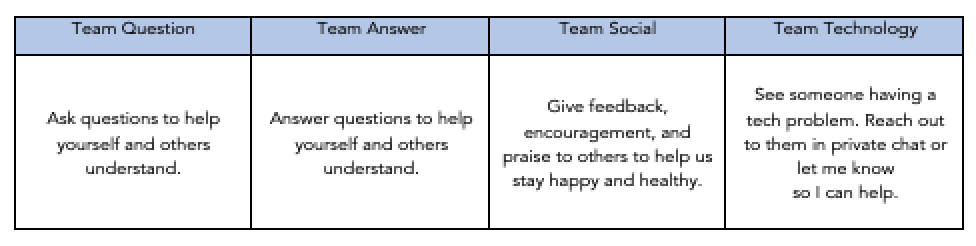

During online presentations and group discussions, consider assigning team roles to encourage engagement and social-emotional support. This can be managed either by introducing team roles before a live session and having students choose or by providing a quick prompt before the beginning of class. The group roles listed in the graphic above are generally useful as a way to improve engagement while also allowing for more emotional support.

Using team roles can further communication while helping peers support each other as we navigate the changes we are all experiencing.

Recognizing and Supporting Both Social and Emotional Needs

As we prepare for back-to-school, be aware of how many learners and educators currently need help and support in managing their social and emotional lives. In the language classroom particularly, some students may struggle to fully express a need for help, which is why it is useful to know indicators that may signal such a need. These include (but are not limited to):

• Sudden changes in a person’s physical state or appearance

• Quick changes in mood or emotional state that are not consistent or normal

• An inability to complete work or a struggle to manage workloads

• Consistent exhaustion, tiredness, or feeling run down

It is important to help students communicate their needs as much as possible, while being aware that everyone will communicate, or fail to communicate, social and emotional needs differently. These types of details can be vital indicators that help may be needed.

As we work with learners during this time, being present and available as educators is important for learner success. More importantly, how we help learners develop the personal skills to navigate the changes they will face now and in the future is critical for overcoming both this current crisis and any that may evolve as we advance into the 21st century.

Notes

For more about the SEL competencies framework, visit https://casel.org/core-competencies.

References

Council of Europe. (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: CUP.

Credé , M., and Kuncel, N. R. (2008). “Study Habits, Skills, and Attitudes: The third pillar supporting collegiate academic performance.” Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(6), 425–453.

Davila, S. (2017). “Teaching in the Zone,” Language Magazine, https://www.languagemagazine.com/2017/08/10/teaching-zone-sara-davila.

de Jong, J., Mayor, M., and Hayes, C. (2016). Developing Global Scale of English Learning Objectives Aligned to the Common European Framework. London: Pearson.

Duckworth, A. L., and Seligman, M. P. (2005). “Self-Discipline Outdoes IQ in Predicting Academic Performance of Adolescents.” Psychological Science, 16(12), 939–944.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., and Schellinger, K. B. (2011). “The Impact of Enhancing Students’ Social and Emotional Learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions.” Child Development, 82, 405–432.

Tangney, J. P. (2004). “High Self-Control Predicts Good Adjustment, Less Pathology, Better Grades, and Interpersonal Success.” Journal of Personality, 72(2), 271–324.

Yarbro, J., and Ventura, M. (2018). Skills for Today: What We Know about Teaching and Assessing Self-Management. London: Pearson.

Sara Davila is a career educator and teacher trainer specializing in English language learning. She implements efficacious learning- design practices into a variety of technology-forward learning experiences for Pearson. She also contributes to the field by providing high-quality, research-informed learning experiences with lesson plans at her website: www.saradavila.com.