Formative assessment is a powerful instructional strategy that plays a crucial role in the education of English learners (ELs) and multilingual learners (MLs). When implemented effectively, formative assessment provides teachers and instructional support staff with actionable feedback that can be used to adjust ongoing language and content instruction, thereby improving students’ academic attainment.

When centered around the unique assets of each learner, the formative assessment process becomes even more effective, especially in the context of ELs and MLs. This article outlines the four key steps in the formative assessment cycle, clarifying the role and importance of student assets.

The Importance of Student Assets in Formative Assessment

At the heart of the four-step process in this new formative assessment framework for ELs and MLs is the recognition and leveraging of student assets. These assets include linguistic, cultural, and experiential strengths that each student brings to the classroom. By understanding and utilizing these assets, teachers can create more meaningful and effective assessments that are truly student-centered.

While traditional formative assessment emphasizes student progress toward content mastery, the framework shared in this article expands this focus to include progress toward both content mastery and language mastery. For ELs and MLs, mastering content is intricately linked to students’ language skills. The framework not only addresses what students need to know and do with language to achieve content objectives but also overlays language form and function onto these objectives. By doing so, it provides a deeper understanding of the interdependence between language and content, ensuring that both are developed in tandem. This student-centered approach leverages the unique assets each student brings, making formative assessment a more holistic and effective tool for educators.

Step 1: Clarifying Intended Language and Learning

The first step in the formative assessment cycle is to clarify the intended language and learning objectives. For EL students to succeed, it is vital that they understand the goals and objectives of their learning tasks. This means clearly defining what students are expected to learn (content goals) and how they will demonstrate their understanding (language goals).

Incorporating language-use expectations based on the task and the students’ proficiency levels is crucial. Explicitly modeling or co-creating these expectations with students can greatly enhance their understanding and engagement. This step also involves ensuring that goals and objectives are not only broad but also specific, concrete, and measurable. By tying these objectives to English language proficiency (ELP) standards, teachers can ensure that their assessments are aligned with both language and content goals.

Without clear goals and objectives, it becomes challenging to design opportunities to assess student progress effectively. Therefore, this step is foundational to the entire formative assessment process.

Step 2: Eliciting Evidence of Language and Content Learning

Once the goals and objectives are clear, the next step is to elicit evidence of language and content learning. This evidence must be observable, meaning that it can be seen, heard, or read. It is essential that the evidence collected is directly tied to the established goals—misaligned evidence cannot provide useful insights into student progress.

Students themselves can be a valuable resource in eliciting evidence. Peer interactions, such as “turn and talk” activities, allow all students to participate and demonstrate their understanding, rather than relying solely on teacher-led questioning. Techniques like eyeball partners (students seated in front), shoulder partners (students seated to the left or right), and clock partners (using a clock template to make appointments with classmates) can facilitate these interactions.

It is important to note that evidence can be elicited both spontaneously during lessons and through planned activities. The key is to create opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning in a variety of ways.

Step 3: Interpreting Evidence

Interpreting the evidence is a critical step in the formative assessment process. As with the elicitation of evidence, interpretation must be closely aligned with the established goals and objectives. Teachers need to analyze whether the evidence shows that students are on track to meet these goals, and if not, what adjustments are necessary.The use of peer-to-peer interaction in interpreting evidence can be particularly beneficial. When students engage in activities like turn and talk, they not only demonstrate their own understanding but also help their peers do the same. This collaborative approach can provide deeper insights into student learning and reveal areas that may need further attention.

Step 4: Acting on Evidence

The final step in the formative assessment cycle is acting on the evidence collected and interpreted. This can be done in a variety of ways, with the primary goal being to provide immediate feedback to students. Feedback should be tailored to the strengths of EL students, whether it is delivered orally, in writing, or through peer interactions. Using students’ native language peers as assets in this process can be particularly effective.

Instructional adjustments based on the evidence can be made either “on the spot” during a lesson or “after the fact” in subsequent lessons. For example, if a teacher notices during a lesson that students are struggling with a particular concept, they can provide additional support immediately. Alternatively, they may choose to revisit the concept in a future lesson based on the evidence collected, if the necessary modifications require additional planning or reteaching.

The Central Role of Student Assets

Throughout the formative assessment process, the central focus remains on the student and their unique assets. By placing student assets at the center of the assessment cycle, teachers can create a more inclusive and effective learning environment for ELs and MLs. Recognizing and leveraging these assets not only enhances the assessment process but also empowers students to take an active role in their own learning.

In summary, formative assessment is not just a tool for measuring student progress; it is a dynamic, student-centered process that, when done well, can transform the educational experience for English and multilingual learners.

Dr. Jobi Lawrence has almost three decades of experience working across all levels in the field of education. From her early career at the local level as a classroom teacher, to serving as the Title III director at a state education agency, to her role at the national level as the director for the National Clearinghouse of English Language Acquisition (NCELA), to her current role as the director of product development and strategic partnerships for UCLA-CRESST supporting ELPA21, she brings a wealth of knowledge and experience in working with students and families. Dr. Lawrence has developed and delivered professional development, publications, guidance documents, and tool kits for use with a variety of education stakeholders to meet the needs of diverse students and their families.

Mainstreaming Multilingualism

As ever, an influx of diverse learners is entering the K–12 system, and the urgency of strengthening equity in education for culturally and linguistically diverse learners cannot be overstated. It is not a “nice to have” approach but a necessity for our educational systems. Equity in education means that each student is afforded the resources and opportunities unique to their needs and necessary for their success while tapping into their rich cultural and linguistic attributes. For culturally and linguistically diverse students, this involves habitually elevating and weaving in their languages and cultures throughout their educational journeys.

Schools strategically adopt structures and frameworks that address long-standing inequities among marginalized populations. A foundational framework widely implemented in recent years is the multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS), which aims to ensure the success of every student. This framework provides a structured system for addressing academic, behavioral, and social–emotional needs through targeted interventions to help all students succeed. MTSS consists of:

- Tier 1: Universal core instruction for all students.

- Tier 2: Targeted interventions for students who need small-group-focused instruction.

- Tier 3: Intensive interventions for individual students with significant needs.

Tier 1 is universal and inclusive of all students in the general education classroom. It provides high-quality, research-based, differentiated instruction and utilizes assessments to identify mastery of grade-level skills, concepts, and remaining academic gaps. Hoover (2013, 2016) suggests approximately 80% of students are expected to achieve academic and behavioral success through robust Tier 1 core instruction. Tier 2 provides targeted intervention to approximately 20% of students identified as being at risk. Tier 3 further intensifies intervention through explicit instruction in a one-to-one setting for, at most, 5% of students.

While this framework offers a structured approach, too often the MTSS framework emphasizes a response to intervention that focuses on students’ skill deficits to close “gaps” identified against norms established by monolingual peers, rather than recognizing and leveraging culturally and linguistically diverse students’ funds of knowledge. The conventional MTSS framework does not explicitly address the distinctive instructional practices fundamental to multilingual learners that differ from those of the English-medium classroom. Hoover et al. (2016) forewarn that although MTSS does support the early identification of struggling learners, it may also leave educators open to misinterpretation of culturally driven behaviors as a need for Tier 2 or 3 intervention. Subsequently, this may also result in an over-identification of multilingual learners for special education. In addition to the negative implications for student success stemming from this misdiagnosis of student needs, it may create an additional, unnecessary burden on special education systems and resources.

It is essential to remember that culture and language acquisition are neither a deficit nor a disability, but rather formidable assets. An equitable MTSS (eMTSS) requires high expectations, an understanding of the needs of students, a goal-oriented mindset, and clear tools to gauge growth (HUGG). This eMTSS with a HUGG is a transformative approach that can uplift students, particularly culturally and linguistically diverse learners. It takes a holistic approach that goes beyond the status quo and integrates an individual’s linguistic repertoire, considerations for language acquisition, identity, and cultural assets. This approach is also mutually beneficial to peers, as this integration of diverse languages and cultures offers expanded knowledge and new learning opportunities.

Overview of eMTSS with a HUGG

To meet the needs of culturally and linguistically diverse students, we must be explicit in providing frequent and ample opportunities for students to lead with their identities, embrace their linguistic repertoires, and connect their multilayered cultures to their learning. McCart and Miller (2020) highlight that the blueprint for success requires educators to identify the what and the why of MTSS as well as to have the ability to put it into practice. eMTSS is a proactive framework that explicitly centers and validates students’ linguistic and cultural diversity as part of an existing MTSS process. HUGG is a tool within this same framework which layers on a continuum of student strengths and language-acquisition supports, allowing educators to incorporate these concepts alongside academic needs or targets.

Figure 1 highlights Tier 1–specific practices. It is important to note that all students fully participate in Tier 1 instruction. For our multilingual learners, this means Tier 1 must include bilingual/dual language education in addition to English as a second language (ESL) and/or English language development (ELD) time. It is not uncommon for the instructional practices of ESL/ELD to be misconstrued as Tier 2 intervention; however, I cannot emphasize strongly enough that multilingualism is not a deficit or disability and should never be treated as such.

Equitable Tier 1 as a nonnegotiable for multilingual learners is no less than the enactment of the educational and civil rights of culturally and linguistically diverse learners.

Although the concepts of the continuum are not new, layering it within the HUGG approach provides an actionable and insightful lens. This allows educators to see the whole culturally and linguistically diverse child and to leverage an improved understanding of language proficiency to make teaching and learning more comprehensible to this population.

This increased understanding is only one advantage of the eMTSS with a HUGG system. It promotes students’ sense of belonging and identity and improves their learning experience, ultimately resulting in stronger academic outcomes. The eMTSS with a HUGG approach does not stop at the classroom level, however. By offering systems-level pedagogical tools, it allows building, district, and even state educational entity staff a way to recognize and leverage students’ assets to transform ideas about what education can look like for all learners. Tier 1 is core instruction and is more complex for multilingual learners. Researchers call attention to the fact that literacy instructional frameworks developed for monolingual learners may not be suitable for biliteracy development and suggest that educators need to understand which linguistic elements do not transfer in order to provide targeted instruction to meet specific needs (Klingner et al., 2016).

Educators play a crucial role in strategically creating these cultural and linguistic connections in ways that help students feel valued and integral to the learning process. Hamayan et al. (2023) identified seven integral factors for understanding a multilingual learner. These seven factors comprehensively understand a student’s past education and home environment, creating a detailed image of their experiences.

Consider, for instance, a newcomer from Nicaragua’s Pacific coast who has recently enrolled in a fifth-grade classroom. As the school team gears up to gather background information about the student’s seven integral factors, the learning in the classroom is in full swing; material may need to be simultaneously supplemented to create engagement opportunities for the newcomer. For example, the student has never experienced snowfall, but the curriculum utilizes a mentor text about a family ski trip to Colorado. eMTSS Tier 1 would call for the instructional plan to draw cultural parallels between the sport of skiing in Colorado and the rich history of surfing on Nicaragua’s Emerald Coast. Even if the student has never surfed the waves of the Pacific Ocean, they would have background knowledge due to the country’s profound coastal history of the sport over the last 40 years, allowing them to connect to the cultural concept of skiing, which is necessary for them to access learning. Instruction may become more linguistically responsive through thoroughly understanding language proficiency levels in Spanish and English. The team may engage in strategic planning that leads to instruction and delivery of the lesson using rich, authentic texts in Spanish. In this manner, Tier 1 addresses the student’s cultural connections and linguistic needs while adhering to the school’s curricular requirements.

A Holistic Framework

Consider Figure 2, the eMTSS with a HUGG framework. On one end of the continuum, Tier 2 and Tier 3 are followed by special education; however, this should not be construed as a deficit. In this image, special education solely represents how culturally and linguistically diverse students may still be referred for eligibility for an individualized education plan (IEP). On the other end of the continuum, Tiers 2 and 3 are followed by gifted education. Gifted education falls under the umbrella of special education;

however, this figure relates to how culturally and linguistically diverse students may also be referred to as challenging educational opportunities. It recognizes that culture and language are incredible assets, symbolizing the necessary shifting and expansion of mindsets and perspectives to acknowledge the full scope of all students. eMTSS with a HUGG exemplifies how individuals have a range of needs, and that offering tailored supports does not preclude engaging educational extensions.

Hollie (2018) states that being culturally and linguistically responsive is not something you do but something intentional and intense in everything we do. Moreover, eMTSS with a HUGG reaffirms Tier 1 as the grounding core for all students. The figure represents that, when our work is rooted in equity and delivered through a culturally and linguistically responsive approach, all students flourish and succeed. These roots represent an understanding of the varying attributes of individual cultures, multilingual proficiencies, what motivates learners, and the assets and experiences they possess. When educators work to understand the depths and breadths of our culturally and linguistically diverse students, we strengthen relationships, cultivate learning, and engage students in leading their educational journeys.

The tree’s trunk represents how we deliver deeply rooted instruction.

This framework helps educators foster students’ assets while targeting required learning through making genuine connections to their experiences. Through culturally and linguistically responsive delivery, we provide tailored instruction, support, and enrichment. As we cultivate this into practice, the tree flourishes; however, when a student displays observable behaviors that lean toward either side of the continuum, then the HUGG layer of the framework comes into play.

When strong Tier 1 practices, as shown in Figure 1, are in place and a multilingual learner needs support or supplementation that is beyond differentiation but is not quite Tier 2, we provide a HUGG:

- High expectations

- Understand their needs

- Goal-oriented

- Gauge growth

Observing and providing explicit differentiation for a culturally and linguistically diverse student who may need additional support or supplementation is essential. Before identifying Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention or enrichment, we must:

Maintain high expectations through questions such as:

- Is instruction grade-level appropriate?

- How do we make it more comprehensible?

- Select and use instructional practices (strategies and materials) that produce comprehensible input and make cultural connections for learners.

- Ensure accessibility.

- Cultivate engagement and motivation to learn by incorporating student interests.

Understand the unique needs of the student by:

- Weighing their strengths as much as their targets.

- Taking into account their entire cultural and linguistic repertoire.

- This means understanding their language-acquisition pathways and utilizing their language-proficiency levels to meet students where they are and plan for where they are going.

- Keeping the goal specific and observable.

- Incorporating pre-assessments and previous evidence of work to strategically build the HUGG based on the student’s unique needs.

Be goal oriented

- Create a Tier 1 goal that:

- Maintains high expectations! We do not lower the bar!

- Is achievable

- Identify the targeted instruction and linguistic supports provided in each language.

- Align to the four language domains.

- Set a language-based goal aligned to academic content.

- Consider the behavioral and social–emotional outcomes of the student.

Gauge the growth

- Identify the EL-based strategies you will use to support the student.

- Identify the tool to monitor progress.

- Set a date for monitoring the progress and discuss it as a grade-level team.

When we explicitly co-create goals for our students, we can address their needs, thoroughly describe observed learning behaviors, and monitor gains related to the unique complexities of multilingual learners. As a team gets to know the student through the integral factors, the HUGG shifts to further align with the student’s academic, behavioral, and social–emotional needs based on multiple data points and historical context. If the student is placed in Tier 2 or 3, the HUGG hones in on the skills, strategies, and tools that align with the overarching Tier 1 HUGG goal.

In short, the eMTSS with a HUGG framework offers an inclusive approach that integrates students’ linguistic and cultural assets, fosters a sense of belonging, builds meaning through a personally relevant lens, and ultimately leads to improved academic outcomes. By acknowledging and fostering the strengths of culturally and linguistically diverse learners, we can address educational inequities and disparities, establishing a holistic and safe learning environment where every student is uplifted and celebrated and can flourish. We must be instrumental in advocating, addressing existing disparities, and guaranteeing that culturally and linguistically diverse students have opportunities to maximize their potential and enrich the classrooms they are part of in the process.

References available at www.languagemagazine.com/references-mainstreaming-multilingualism

Muriel Ortiz is an experienced educator and administrator in K–12 public education. She is a dedicated educational consultant at Adelante Educational Specialists Group and coordinator at Smarter Balanced, a nonprofit assessment consortium through the University of California. She has a proven track record of consulting, developing, and coaching district and school leaders on dual language and EL program design, implementation, and evaluation, as well as culturally and linguistically responsive MTSS, biliteracy instruction, and second language acquisition.

Muriel is passionate about disrupting the status quo and creating an equitable, innovative, and engaging learning environment for multilingual learners. She holds multiple certifications and endorsements in bilingual and special education and is pursuing a PhD at DePaul University.

Using AI to Save Time and Lessen the Load

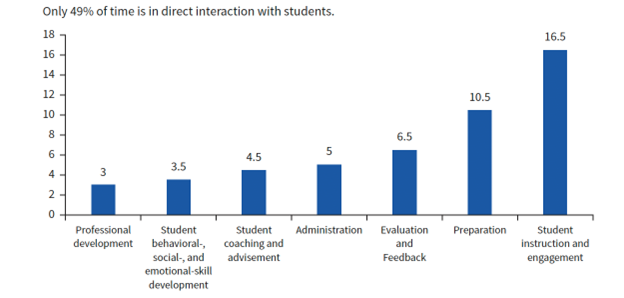

Most would agree that time is something we always seem to be short of and always want more of. The phrase “there are not enough hours in the day” resonates throughout many professions, but it rings particularly true in education. And it isn’t just a matter of perception. Microsoft partnered with McKinsey and Company to survey teacher time use. They found that the 50 hours of work teachers reported weekly were divided among many important planning, administrative, and professional learning responsibilities (McKinsey and Company, 2020). However, this leaves surprisingly few hours remaining for student instruction, reported worldwide as the most satisfying aspect of teaching (Ainley and Carsten, 2018). In fact, only 24.5 hours—49% of time— were dedicated to direct interaction with students (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fifty average hours of working time per week for a teacher

Source: Hargrave, M., Fisher, D., and Frey, N. (2024). The Artificial Intelligence Playbook: Time-Saving Tools for Teachers That Make Learning More Engaging (p. 5). Corwin. Used with permission.

Since generative artificial intelligence (AI) began making its way into education in early 2023, it has presented itself as a tool that genuinely seems to offer the potential of addressing this concern. While it’s not a fix-all—the human user is still very much needed when using the tools—it has already shown that it can significantly assist in some of the important but time-consuming tasks vying for a teacher’s time.

Generative AI tools are designed to generate content quickly and accomplish tasks in human-like ways, all in very short amounts of time. As many already know, chatbots (AI-powered software applications designed to simulate human conversation to obtain information or perform tasks) respond to user prompts. These requests can yield unit plans, a series of multiple-choice questions and short constructed writing prompts for an assessment, or pages of math word problems in just minutes. If you have already started exploring these tools, then you, like many, have experienced moments of shock when you saw how quickly generative artificial intelligence can perform tasks that might otherwise take hours or days to complete. Having access to tools that can perform tasks in a fraction of the time is a game-changer, but knowing where to start and how to make qualitative improvements is essential. With that in mind, we outline three places to start when it comes to using AI as a time-saving tool. We conclude with cautions about the judicious use of AI.

Tip #1: Generate More of What Works

AI platforms do a good job of mimicking existing quality materials, making them an ideal tool when a language teacher wants to generate more of something already in use. This is a great place to start for those unsure about how and where AI can save them time because users can build on what they have already found to be useful for their students. They know what they are looking for and are generating materials that are familiar. For example, AI can create another example about a new topic for a writing lesson, replicate a successful science experiment with a new focus, or create more word sorts to use in an early literacy or vocabulary lesson. Using a text analyzer, it can develop new comprehension questions for a reading, or translate a rubric into another language.

Tip #2: Overcome “Blank Page” Moments

All educators are familiar with the challenges of conceptualizing new ideas, possible interventions, novel spins on an assignment, or additional methods to practice a skill. We sit at the computer in front of a blank page, visit some go-to sites looking for ideas, or flip through curriculum resources to find something that may or may not be there. Meanwhile, the minutes tick by. AI is here to help. Some have described it as much like an intern or thought partner, both titles that credit it for being able to move users beyond the writer’s block we may experience. It can be as simple as saying, “What do you think about this?” or “List some ideas to help a student who needs _____ and ____.” What we have learned is that chatbots give many more ideas than we might want or need. Some are good and others not so good, but it is a way of getting a toehold to further develop plans using your expertise.

A chatbot can be used by a team of teachers to develop a possible list of learning intentions and success criteria for a new instructional unit. There is strong evidence that the regular dialogic use of learning intentions and success criteria holds the potential to accelerate student learning (Hattie, 2023). However, teachers can get bogged down in crafting them. Load the targeted standards for the unit into the chatbot, specify the grade level and the number of days for the unit, and tell it to develop daily learning intentions and success criteria for each day. Review the suggestions and provide additional feedback to revise (e.g., “Phrase all the success criteria as I-can statements.”) The team can then discuss the merits of the suggestions, customizing them to best fit their context. Rather than facing a blank page, the team can engage in rich dialogue about their learning goals.

Tip #3: Organize and Streamline

It takes time to regroup students using data from a written response or exit ticket, or to combine individual responses into a single class statement. There can be a significant amount of time spent organizing materials before the real work of looking at those materials even begins. AI can help lighten this load. It can efficiently organize work into predefined categories, sort responses according to a provided rubric, and quickly turn multiple short answers into one comprehensive response. Also, if a user isn’t sure how to organize something—what order to put things in, what categories to include on a rubric, or what similarities or differences responses have—with a simple request, the technology can assist.

Automating and speeding up these tasks frees up educators to focus on what really matters: analyzing and discussing the work itself. However, it is important to ensure that specific student data are not included when using AI in this way. We have found that having students respond via a Google Form using an assigned student number or simply omitting names from inputs has helped teachers use AI as a time-saver while still adhering to data security standards.

Find Balance in Hybrid Human–AI Generated Content

Thinking of AI as an intern can significantly enhance the efficiency and effectiveness with which technology works for you. When using a generative AI platform, input all relevant information just as you would discuss a project with a colleague. If possible, specify the ideal format, content that should be included, standards to address, and any additional details that you as the experienced educator have in mind. For instance, rather than saying, “I need something for science,” it’s more effective to state, “I need a lesson plan for ninth-grade biology that covers photosynthesis and cellular respiration. It should include a lab activity and a quiz.” Eaton (2023) refers to this approach as “hybrid human–AI generated content” (p. 3) and predicts that this collaborative method between humans and AI will become the typical style of writing in years to come.

Analyze Output and Writing Prompts

It is crucial to maintain control over the content we use for teaching and learning, especially when incorporating AI. Access to AI as a time-saving resource is beneficial only if the quality of teaching materials remains high. Learning to efficiently and productively analyze output is an important skill for those starting to use this technology for daily tasks. Start by verifying the accuracy of the content: Is it true? Does it exhibit bias? Are there missing perspectives? Next, look at the clarity and voice of the output, making sure it matches your teaching style and meets the needs of learners in front of you.

As Ethan Mollick suggests in his book, Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI (2024), inviting AI to the table is a way we can see its capabilities in terms of saving time on regular functions and tasks. This does not mean it will always help, but it does mean we can start getting in the habit of asking ourselves the questions, “Is this something AI can help us with? Is there a part of this task that could be done more efficiently with AI assistance?” The more we start to invite this technology in, the more we can explore its capabilities and learn about its limitations.

Access for Multilingual Learners Depends on Their Teachers

Andreas Schleicher, director of education and skills at the OECD, cautions us that our task is to “educate students for their future, not our past” (2018). Against the backdrop of the “unequal history of learning technologies,” a new global digital divide is emerging when it comes to the use of generative artificial intelligence (Regmi, 2023, p. 437). Language teachers can and should be at the forefront of leading their students in the accurate and ethical use of AI. It begins with incorporating the judicious use of AI tools to expand what we value most—time with our students.

Resources

Ainley, J., and Carstens, R. (2018). “Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS) 2018 Conceptual Framework.” OECD Education Working Papers No. 187. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Publishing, Paris. https://doi.org/10.1787/799337c2-en

Eaton, S. E. (2023). “Postplagiarism: Transdisciplinary ethics and integrity in the age of artificial intelligence and neurotechnology.” International Journal for Educational Integrity, 19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40979-023-00144-1

Hattie, J. A. (2023). Visible Learning: The Sequel. A Synthesis of Over 2100 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. Routledge.

McKinsey and Company (2020). “How Artificial Intelligence Will Impact K–12 Teachers.” www.mckinsey.com/industries/education/our-insights/how-artificial-intelligence-will-impact-k-12-teachers

Mollick, E. (2024). Co-Intelligence: Living and Working with AI. Portfolio.

Schleicher, A. (2018). “Educating Students for Their Future, Not Our Past.” Teacher Magazine. www.teachermagazine.com/au_en/articles/educating-students-for-their-future-not-our-past

Meghan Hargrave is an experienced educator. After being a teacher leader in the classroom, she moved into education coaching and consulting where she supports hundreds of K-12 schools and districts worldwide. Her work has always focused on important instructional shifts in education and practical ways the educators she supports can embrace these shifts effectively, which has included the integration of Artificial Intelligence tools in the classroom. She is ChatGPT, GoogleAI, and AI for Education certified in addition to working closely with thousands of educators on how to implement these tools in the classroom. She is an international presenter, has taught preservice teachers at Columbia University’s Teachers College, regularly contributes to popular educational publications, and is known for sharing innovative and effective classroom strategies via social media @letmeknowhowitgoes.

Douglas Fisher is professor and chair of educational leadership at San Diego State University and a leader at Health Sciences High and Middle College. Previously, Doug was an early intervention teacher and elementary school educator. He is a credentialed teacher and leader in California. In 2022, he was inducted into the Reading Hall of Fame by the Literacy Research Association. He has published widely on literacy, quality instruction, and assessment, as well as books such as Welcome to Teaching, PLC+, Teaching Students to Drive their Learning, and Student Assessment: Better Evidence, Better Decisions, Better Learning.

Nancy Frey is professor of educational leadership at San Diego State University and a leader at Health Sciences High and Middle College. Previously, Nancy was a teacher, academic coach, and central office resource coordinator in Florida. She is a credentialed special educator, reading specialist, and administrator in California. She is a member of the International Literacy Association’s Literacy Research Panel and has published widely, including books such as Welcome to Teaching, PLC+, Teaching Students to Drive their Learning, and Student Assessment: Better Evidence, Better Decisions, Better Learning.

Chinese Focus on Traditional Culture and Language

Starting this semester, China’s national school curriculum will focus more on national security and traditional culture. Primary and junior high school students starting the autumn semester will be given new textbooks on Chinese language and history as well as morality and law, announced state broadcaster CCTV.

“Morality and law” was known as ideology and politics until 2016. It is a mandatory subject that promotes the ideology of the ruling Communist Party.

Included in the new textbooks are sections on the president’s political philosophy, Xi Jinping Thought. There will also be an emphasis on traditional Chinese culture and national security, according to a Ministry of Education official cited in the report.

All Chinese students receive nine years of compulsory education, six in primary school and the rest in junior high. The new textbooks will initially be used in the first and seventh grades and will be extended to all nine grades within three years, says CCTV.

The new morality and law textbook would introduce the “main content and historical status” of Xi Jinping Thought, the report said.

Officially known as “Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era,” Xi’s political philosophy was enshrined in China’s constitution in 2018.

Chinese language textbooks will include more ancient Chinese literature and stories about the revolutionary years before the party won the civil war in 1949, establishing the People’s Republic.

It’s September. Do You Know Where Your Learners Are?

As the new school year begins, understanding each learner’s language proficiency is crucial for effective instruction. The ACTFL Assessment of Performance toward Proficiency in Languages (AAPPL) is a powerful tool for educators to gauge students’ skills right from the start.

Accurate Placement: Proper placement is key to ensuring learners are neither overwhelmed nor under-challenged. The AAPPL provides a good picture of each learner’s level on the ACTFL scale, allowing educators to place them in the appropriate class that matches their skill set.

Tailored Instruction: By tailoring instruction based on insights from AAPPL scores, teachers can create a more personalized learning experience. This not only helps in addressing individual areas for improvement but also builds on each learner’s strengths, fostering a more engaging and effective learning environment.

Goal Setting: For students pursuing the Seal of Biliteracy, early AAPPL assessment helps set realistic goals. Knowing their starting point, learners can track progress and stay motivated.

Curriculum Development: Early proficiency assessments provide critical data that can inform instructional planning. By analyzing AAPPL results, educators can identify areas of strength and opportunities for improvement across their student population.

Credible Assessment: The AAPPL is a valid and reliable measure of learners’ performance toward proficiency, scored by ACTFL-certified raters and based on the ACTFL Proficiency Guidelines–2024. This means that the results are not only accurate but also recognized and respected within the educational community.

Stakeholder Communication: The detailed AAPPL reports help educators communicate learners’ progress clearly to parents and stakeholders, fostering collaboration.

Start the school year with the AAPPL, the only official ACTFL assessments for learners in grades 3–12, and support your learners’ success in language proficiency.

www.languagetesting.com

Power Up Language Learning with the Proficiency Cycle

“How can we elevate our language learners, celebrate their hard-earned talents, and bring our program to new heights?” The answer? Harness the magic of data. Educators are guiding stars, illuminating each step of the proficiency cycle for their learners: a transformative journey of assessment, insight, learning acceleration, and the thrill of achievement. Avant is here to support and amplify this incredible journey.

Assessment for Growth and Opportunity. Imagine test results that actually provide you with a road map tailored for every learner, one where each Power-Up milestone feels like a personal triumph. True growth isn’t limited to an annual exam. It’s the everyday victories, the small but tangible steps forward. Avant STAMP isn’t just any assessment tool—it’s the gold standard, available in 48 languages, including ASL and Latin.

With endorsements from the prestigious American Council on Education (ACE), now including STAMP for ASL, pathways light up from K–12 to higher education in recognition of the skills learners have acquired leading up to college. When you need to support multilingual learners and help them power up, our Spanish Heritage Test and STAMP for English fill in the gaps for placement and curriculum development.

Personalized Journeys. Avant is pleased to announce the launch of a revolutionary new productive skill-enhancing tool: MeTabi Coach+. This classroom companion leverages AI for unlimited practice with real-world use of language. With this enriching platform, educators can sculpt lessons and interventions that resonate, inspire, and elevate. The new MeTabi Multilingual Family Assistant can be hosted on your website to help multilingual families navigate everyday interactions with your school or district.

Teacher Professional Learning. Picture a classroom where teachers brim with confidence, their enthusiasm infectious. With Avant ADVANCE and Avant MORE Learning, educators are architects of dreams, armed with a profound understanding of proficiency guidelines and data wizardry. And with our elite team of experts at MEDLI supporting you, your dual language/bilingual immersion programs aren’t just effective—they’re revolutionary.

College and Career Pathways. Avant STAMP isn’t just an assessment—it’s a passport to powerful credentials, including the prestigious State and Global Seals of Biliteracy. Teachers and students proudly pin these badges onto their profiles, college applications, and resumes. Learners aren’t just showcasing their skills—they’re announcing to the world their readiness for global adventures and opportunities in the working world.

With Avant’s unmatched expertise, your language program won’t just progress—it will soar. Ready for a journey that redefines limits and ignites dreams?

avantassessment.com

Literacy Intervention Solution Helps Grow Students’ Foundational Reading Skills

With up to 50% of US students struggling with the foundational skills they need to become fluent readers, educators need easy-to-implement literacy interventions to help students, especially those in middle school and above, get on the path to fluency.

WordFlight is designed to help. This unique, evidence-based online solution for students in grades 3–8 bridges the gap between phonics and fluency by focusing on automatic word recognition—a critical and often overlooked skill needed for students to become fluent readers.

Aligned with the science of reading and based in the science of learning, the online program’s powerful combination of components—screener, patented diagnostic, instructional program, teacher resources, and ongoing implementation support—helps students move beyond decoding to learn how to use letter–sound relationships in a way that results in automatic word recognition. WordFlight helps students develop the word-level fluency that is necessary to read fluently for comprehension.

The program leverages adaptive technology and provides personalized, structured practice in an engaging game-like environment that makes learning stick. Throughout the program, students experience varied task difficulty, context changes, and ongoing feedback.

When implemented with fidelity, WordFlight helps move students to proficient in foundational reading skills. In fact, one dual immersion teacher in California saw the number of students scoring as proficient in phonics and fluency double on the FastBridge assessment after only four months of using the program.

A majority of students in the class also improved their proficiency in automatic word recognition and decoding, as measured by the patented WordFlight Diagnostic. Notably, the program has additionally been shown to help move 80% of struggling middle school students to proficient in foundational reading skills within one school year.

Learn more about WordFlight at www.wordflight.com.

Breaking Down the Monolingual Wall VIII: Our Students Are Multilingual. Shouldn’t Assessment Be?

It’s the first quarter of the academic year, and schools have just received the results of the district’s initial round of interim achievement tests. With programmatic, classroom, and individual student decisions to be made, grade-level, department, and leadership teams convene to dive into the data. Teachers notice that several multilingual learners’ scores on these measures are not reflective of those on their state achievement tests. Digging deeper, they realize that the interim tests and the annual state tests serve distinct purposes and have different measurement scales. While the interim tests provide baseline data for determining student growth over the year, annual state test data contribute to school accountability and program evaluation from year to year. The teachers are at a crossroads as to what to do with the conflicting information and how to plan individual learning goals with their students for the semester ahead.

Teachers often wonder why major instructional decisions tend to be based on results from standardized tests. They question why data from measures in English tend to prevail when their multilingual learners, by definition, are exposed to and interact in multiple languages. After all, shouldn’t these students be advantaged by having access to multilingual resources for instruction and multiple sources of information for assessment? Let’s investigate this matter a bit further.

There seems to be two assessment-related issues to examine here. The first addresses the paradox of the steadily growing multilingual school population juxtaposed to continued allegiance of assessment to English. Despite the welcoming of languages and cultures in classrooms and hallways, assessment tends to remain steadfastly monolingual. It’s time to revisit the privileging of English in assessment practices for multilingual learners and introduce multilingual multimodal ways to capture student growth.

The second issue pertains to the heavy reliance on decontextualized numbers and letters to make high-stakes decisions, at times, even depersonalizing multilingual learners, reducing their identities to a single number (e.g., “He’s a 3.”). We question the meaning of these outcomes when test scores are presented in isolation, especially when they depict only a slice of a student’s multilingual repertoire. How can teachers along with school and district leaders use these data to inform teaching and learning without having a sense of the multilingual learners’ bi/multiliteracy potential? How can these data alone evoke teacher and multilingual learner agency (Gottlieb, 2024)?

This article presents a case for resolving these dilemmas and convincing you of the resourcefulness of multilingual learners when they have entrée to and options for using multilingual resources for classroom assessment. By optimizing strengths-driven assessment, the option of multiple languages should be non-negotiable for these students. We intend to persuade you to take a multilingual stance, if you haven’t already, based on a set of premises:

- Increasing multilingual learners’ access to and use of multiple languages for instruction and assessment yield more equitable, realistic, and useful information for making meaningful decisions.

- Interweaving classroom assessment and instruction afford teachers ways to strategize and chronicle students’ multilingualism and multiculturalism while accentuating linguistic and cultural sustainability.

- Co-constructing assessment-embedded instruction with multilingual learners optimizes student choice and voice, bolstering multilingual learners’ motivation and self-assurance.

Changing the Monolingual Testing Mindset to Assessment in Multiple Languages

According to Jeff Zwiers (2024), “prevailing U.S. pedagogy tends to focus on preparing students to score well on multiple choice tests”. In large part, these tests, as those in the opening scenario, are part of local and state accountability systems. We might ask, ‘How do the results from these discrete measures impact individual multilingual learners and how can we offset their negative effects to accentuate our students’ multilingual assets’?

In shifting from a testing to an assessment mindset, we abandon reliance on a single data point and place our trust on a range of data sources; thus, we become more open to gathering information in multiple languages. In moving from testing in English (a monoglossic orientation) to a more heteroglossic one for assessment, we uncover possibilities for multilingual learners’ increased engagement (García, Kleifgen, & Fachi, 2008). We respond to this issue in Figure 1 by contrasting testing inequities inherent in one language with equitable assessment moves in multiple languages.

Figure 1. Counteracting Testing Only in English With Assessment in Multiple Languages

| Inequities in Testing Multilingual Learners Only in English | Assessment Equity in Multiple Languages: What We Can Do |

| Tests generally have a White middle-class linguistic and cultural orientation. | Offer students resources from multiple language varieties and cultural perspectives. |

| Tests are designed for and geared to monolingual outcomes. | Ensure assessment can capture student learning in multiple languages, no matter the language(s) of instruction. |

| Test results tend to be presented as scores or numbers. | Complement testing results with criteria for success based on multimodal evidence in multiple languages. |

| High-stakes tests generally do not represent the local curriculum. | Consider testing results as one data source; include additional information internal to local curriculum and instruction. |

| Content and language are often confounded in achievement tests. | Utilize multimodalities (e.g., audio, visuals, graphics, the arts) in combination with content to enhance student accessibility during instruction and assessment. |

| Standardized achievement tests usually consist of unrelated items. | Balance testing with documentation from project-based, place-based, or inquiry-based instruction and assessment. |

| Standardized achievement tests most likely have been normed on predominantly monolingual student populations. | Become assessment literate, aware of reliability, validity, and fairness issues of testing and their potential impact on multilingual learners. |

| Standardized achievement tests may not take multilingual multicultural perspectives into account, thereby producing bias and sensitivity issues. | Volunteer to participate on panels and committees that examine issues of bias, sensitivity, and accessibility. |

Testing in a single language can provide neither a full nor authentic portrayal of multilingual learners. Assessment, in contrast, entails an array of artifacts in one or more languages to more comprehensively show multilingual learners’ growth and attainment. Multilingual learners should be contributors to and vested in the assessment process.

Strategizing How to Implement Assessment in Multiple Languages

Every educator of multilingual learners, whether monolingual or a polyglot, can assume an agentive and advocacy role in highlighting student strengths in curriculum, instruction, and classroom assessment. For those of you who declare, “There are multilingual learners from 10 languages and cultures in my classroom; how can I equitably assess their conceptual and language development?” or “How can I secure multilingual resources when I am monolingual?” It can be done if you adopt multilingualism as the norm and engage in collaborative assessment with colleagues and your multilingual learners (Gottlieb & Honigsfeld, 2025).

The following are my top ten student-centered strategies for instruction and classroom assessment (in no particular order):

- Invite students to choose among multimodalities (linguistic, visual, graphic, spatial, kinesthetic in combination with text) to demonstrate their learning for units of learning and individual lessons.

- Expand accessibility of multilingual digital resources across content areas through apps and internet sites (don’t forget artificial intelligence).

- Highlight student-student interaction in their shared languages throughout the instructional and assessment cycles.

- Promote student self-assessment in the language(s) of their choice for reflecting on learning or applying a set of agreed upon descriptors to their work.

- Utilize (standards-referenced) criteria for success for peer assessment and have classmates exchange concrete actionable feedback with each other.

- Compile and maintain a schoolwide multilingual resource bank of student/family expertise and multilingual community services that tie to student experiences.

- Organize a buddy system between different grades with regular structured exchanges to further students’ (bi)literacy development.

- Arrange tutorials between older and younger multilingual learners of the same partner language to help meet individual learning goals.

- Incentivize middle and high school students to participate in service learning and apprenticeships, including options in multiple languages.

- Encourage translanguaging as a form of student expression in oral and/or written communication.

Committing to Fair and Equitable Assessment Practices for Multilingual Learners

Multilingual learners are constantly navigating within and across ecosystems where the languages of the home, school, and community interact (see Figure 2). Although linguistically and culturally sustainable classrooms offer space for multilingual learners to engage in and make connections across these ecosystems, unfortunately, the natural interweaving and flow of languages and cultures generally do not extend to assessment policy and practice (Zacarian, Calderón, & Gottlieb, 2021).

Figure 2. The Linguistic Worlds of Multilingual Learners

Soto, et.al, 2023, p.93

By embracing these interconnected ecosystems, we accept and build on students’ language and cultural capital. However, if multilingual learners’ entire school experience is confined to English, there will always be discontinuity. In valuing the languages of learning inside and out of school, we must commit to securing resources in multiple languages while fortifying those of our students and their families. Consequently, we must insist on congruence between the languages and cultures of multilingual learners and local assessment practices.

Expanding Language Proficiency Assessment

Standardized testing comes with specific requirements for administration and interpretation of results. Educators of multilingual learners must be aware of its regulations, constraints, and benefits for both academic achievement and language proficiency. English language proficiency testing is unique in that it is:

- Federally mandated (ESEA Section 1111(b)(1)(F) for a subset of multilingual learners

- Applicable across the K-12 spectrum

- Aligned to English language proficiency/ development standards

- Administered on an annual basis across language domains

- The primary state metric for determining students’ English language growth

- A tool that contributes to reclassification of multilingual learners categorized as ‘English Learners.’

Many educators, however, have broadened the scope of what constitutes language proficiency,shifting from examining language development solely in English to being more inclusive of students’ multilingualism. With expanded instructional and classroom assessment practices, teachers are moving away from language proficiency as domain specific (listening, speaking, reading, and writing) to envisioning language development as integral to students’ identity formation, including their metacognitive, metalinguistic, and metacultural influences (Gottlieb, 2024; Gottlieb & Leung, 2024). In other words, multilingual learners, in some situations, are no longer being defined according to a score on a test in English, but rather, according to the totality of their lived experiences.

A common activity exclusive to multilinguals is translanguaging, the dynamic, natural, fluid, and meaningful flow of languages between/among bilinguals that has been embraced and researched worldwide. As an invaluable contributor to multilingual learners’ development and self-worth, translanguaging exemplifies and reinforces the strengths of multilingualism. Figure 3 offers ideas for incorporating multiple languages, together with translanguaging, into instruction and classroom assessment.

Figure 3 Translanguaging as an Instructional and Assessment Norm for Multilingual Learners

| Teacher Moves to Stimulate Instruction and Assessment in Multiple Languages | Multilingual Learners’ Opportunities to Translanguage During Instruction and Assessment |

| Co-create with students learning goals for units of learning or learning targets for lessons attainable in multiple languages | Co-plan with teachers ways of presenting learning using one or more languages |

| Invite multilingual learners to thoughtfully choose one or multiple languages to explore different avenues to learning | Use multilingual multimodal means (e.g., bilingual videos, podcasts, and AI) to examine, explore, and share content |

| Offer an array of language and multimodal resources of interest to students | Produce multilingual multimodal evidence, such as audio recordings, videos, multimedia, labeled graphics, or kinesthetics to showcase learning |

| Encourage student discussions in small groups with interaction in multiple shared languages | Create products, projects, or performances in teams according to bilingual criteria for success |

| Pair students of the same partner language to reflect on learning and give each other feedback | Engage in peer assessment based on familiar descriptors in students’ language(s) of choice |

Adapted from Soto, et.al, 2023.

Taking Action

The benefits of multilingualism are well-documented and are becoming increasingly visible across classrooms, schools, districts, and states. If we accept these advantages as integral to the collective multilingual learner identity, then educational stakeholders must support assessment in multiple languages. Taking this proposition further, the acceptance of multiple language use requires a shift in mindset to one of multilingualism and multiculturalism reflective of multilingual learners’ communities, homes, and schools. The following suggested actions are a starting point for you and your colleagues to initiate or acknowledge change in your local assessment practices.

- Introduce school and community-wide multilingual multicultural campaigns or projects as outgrowths of curriculum, instruction, and assessment.

- Invite multilingual learners to take agentive roles in classroom assessment by co-constructing goals for learning and their pathways to learning along with accompanying evidence.

- Elicit support of families in sharing their skills and expertise in multiple languages to embed into instruction and assessment.

- Establish ongoing professional learning around assessment literacy in multiple languages for school/district leaders, teachers, and families.

- Devote time for grade-level teams of teachers and coaches to collaborate in taking data-dives at critical points in the school year (e.g., on a quarterly basis).

- Make decisions with your multilingual learners based on multilingual sources.

Accepting the changing landscape from testing exclusively in English to assessment in multiple languages for teachers with multilingual learners is nothing short of a paradigm shift. We must cast away equating assessment with decontextualized test scores or performance levels generated from monolingual measures to envisioning assessment as an ongoing process of gathering and analyzing multimodal multilingual data to reveal a comprehensive story of who our students truly are and their growth over time. In doing so, we honor and uphold the invaluable contributions of our multilingual learners, multilingual families, and educators. In transitioning to assessment inclusive of our students’ many languages and cultures, it’s time to revisit how we may have been privileging English and take the multilingual turn (May, 2014) to reform our assessment practices.

References

García, O., Kleifgen, J. A., & Fuchi, L. (2008). From English language learners to emergent bilinguals. Equity Matters: Research Review 1. Teachers College.

Gottlieb, M. (2021). Classroom assessment in multiple languages: A handbook for teachers. Corwin

Gottlieb, M. (2024). Assessing multilingual learners: Bridges to empowerment (3e). Corwin.

Gottlieb, M., & Honigsfeld, A. (2025). Collaborative assessment for multilingual learners and teachers: Pathways to partnerships. Corwin.

Gottlieb, M., & Leung, C. (2024, March). Situated language proficiency: revisiting the relationship between construct and use in linguistically diverse settings. Presentation at the AAAL Conference, Houston.

May, S. (2014). Disciplinary divides, knowledge construction, and the multilingual turn. In S. May (Ed.), The multilingual turn: Implications for SLA, TESOL and bilingual education (pp. 7–31). New York, NY: Routledge.

Soto, I., Synder, S., Calderón, M., Gottlieb, M., Honigsfeld, A., Lachance, J., Marshall, M., Nungaray, D., Flores, R., & Scott, L. (2023). Breaking down the monolingual wall: Essential shifts for multilingual learners’ success. Corwin.

Zacarian, D., Calderón, M. E., & Gottlieb, M. (2021). Beyond crisis: Overcoming linguistic and cultural inequities in communities, schools, and classrooms. Corwin.

Zwiers, J. (2024, February). Foster pedagogical justice for multilingual learners. Corwin Connect.

Margo Gottlieb, Ph.D., co-founder and lead developer of WIDA at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, has authored, co-authored, and co-edited 18 Corwin books, accentuating the power of multilingualism of multilingual learners and their teachers in instruction and classroom assessment. She can be contacted at margogottlieb@gmail.com.

Intelligent Assessment

If the words AI and assessment are in the same sentence, the knee-jerk reaction is panic, as fears of technophobia, over-standardization, miscalculation, bias, security, and mistrust are mixed together in the minds of many students and educators.

As generative AI continues to revolutionize teaching and learning, it’s important for both educators and students to understand how this technology impacts assessment practices.

First of all, we need to recognize that AI is not a fad, but a major step in the progress of educational technology. It’s here for good, so students should be prepared and assessed for a world in which they will use AI every day. At the same time, teachers should be embracing AI’s capacity to relieve the grind, especially when it comes to assessment. Traditionally, assessing students’ language proficiency levels has been a labor-intensive and time-consuming process. The advent of AI language assessments has revolutionized this practice by using machine learning technology, trained on extensive datasets, to emulate human judgment. Automated essay evaluation software has been gradually improving over decades, and now powered with today’s AI tools, it is changing our approach to student evaluations.

The flexibility offered by AI language assessments should be harnessed to provide tailored assessments for multilingual learners, leaving no place for standardized testing, which was so often deficit focused. In the same way that students have been trusted to use calculators in exams for decades, we will have to trust students to use AI responsibly—and that will mean encouraging community and fostering transparency so that students learn to use AI tools to hone their personal expertise, rather than as a substitute for it.

Whether the AI tools are being used by educators and administrators to assess students or by students to help them perform better in assessments, the net result will hopefully be more time for both educators and students to focus on personal growth goals, more reflective learning, and identification of gaps in knowledge or areas that could do with improvement.

AI offers even more potential than traditional educational technology for differentiated learning and assessment, plus the relief of some burdensome tasks for educators and administrators, but it will only be truly a step forward when it is adopted within the context of a whole-school approach in which students, educators, and administrators learn and collaborate to best implement the technology, while always focusing on its effect on the most disadvantaged students, who may be the least able to benefit from its advantages.

Daniel Ward, Editor

Israel Introduces Mandatory Hebrew Tests

According to According to the Jerusalem Post, for the first time ever, Israeli Education Minister Yoav Kisch plans to conduct mandatory Hebrew testing for Arabic-speaking students.

The tests will be conducted in one-third of schools annually for 6th-grade students as of 2025 and 9th-grade students as of 2026. According to the Education Ministry, the move is being made in response to the declining results of Arabic-speaking students in language-based subjects and in light of Hebrew’s “importance for integration into Israeli society, academia, and the labor market.” Previously, the tests were not mandatory for schools and were conducted on a representative sample of classes only.

The Hebrew for Life program will operate in all educational frameworks for Arab and Bedouin societies, from first grade to twelfth grade. At the same time, the ministry is promoting the recognition of Hebrew studies as a mandatory subject in Arab education.

“Proficiency in the Hebrew language is a necessary condition for the integration of the Arab community into the fabric of Israeli society,” said Kisch.

“Low proficiency in the language is a significant barrier for students. Our goal is to remove the barriers facing students to ensure their future in academia and the job market.”

Last year’s passing of a law that removes Arabic as an official language in Israel has upset the country’s Arab minority, who have criticized the legislation.

There are roughly 1.8 million Arabs in Israel, making up about a fifth of the state’s population. They are mostly Palestinians and their descendants who remained in place after the 1948 war between Arabs and Jews. Hundreds of thousands of others were displaced or fled.