Kate Kinsella tackles the particular challenges of preparing learners to be able to analyze and discuss complex informational text

The Common Core State Standards (CCSS, 2010) for reading focus heavily on students gathering evidence, knowledge, and insights from what they read. In fact, 80-90% of the reading standards in every grade require text-dependent analysis — being able to answer questions only by referring back to the assigned text, not by drawing upon and referencing prior knowledge and experiences. Equal emphasis is placed on the sophistication of what students read and the skill with which they read. With an aim of equipping students with 21st-century literacy and learning skills for college and the global workplace, the standards demand an increased percentage of informational text exposure and rigor as students advance in their coursework. As early as the primary grades, emergent readers are grappling in English language arts with informational texts along with the traditional literature mainstays. By secondary school, the curricular balance is clearly skewed toward more concept- and data-driven reading and response.

Common Preparations for CCSS Informational Text Reading Emphasis

Given the decisive shift toward informational text reading and evidence-based response, school districts from California to New York are working earnestly to integrate more complex informational text assignments into English language arts curricula and other core subject areas. Similarly, disciplinary and grade-level teams are collaborating on writing text-dependent questions that will ensure students do more than a cursory reading. Close analytic reading of an informational text involves returning to the text to conscientiously identify significant arguments and evidence before scrutinizing the author’s support and language use.

Assessments requiring objective, text-dependent responses are additionally prompting teachers to refrain from instructional practices that actually discourage students from delving into complex nonfiction selections, such as assigning personal response journals or providing detailed Cornell notes for students to copy and study.

Vocabulary Warrants Instructional Primacy

While these curricular involvements are well warranted, less-proficient readers and English learners will need far more than an increase in text and task complexity to engage in competent text investigation and response.

Integrating targeted and systematic vocabulary instruction to support reading comprehension is an instructional imperative. Leaving vulnerable students with acute vocabulary voids to their own devices to navigate lexical landmines in core curricula will not build young reader competence or resiliency. Numerous studies in K-12 contexts have clearly documented the strong and reciprocal relationship between vocabulary knowledge and reading comprehension for native English speakers (Graves, 2000; Stahl, 1999). Extensive research focused on school-age English learners similarly correlates vocabulary knowledge with second-language reading comprehension and other measures of academic achievement, including test scores and writing (August & Shanahan, 2006; Carlo et al, 2005).

By selectively and effectively addressing high-yield words within complex texts, teachers across subject areas can manageably and productively enhance reading comprehension while assisting their students in building a practical vocabulary toolkit they can apply to related response tasks. When serving mixed-ability classes including English learners and striving readers, explicit, interactive instruction will reap the greatest text comprehension gains when words are related to focal lesson concepts or when words have general utility in academic contexts. Kinsella (2013) provides a detailed scheme for analyzing informational and narrative text and prioritizing vocabulary for more robust instruction to maximize comprehension and bolster communicative competence.

A Neglected Component of Informational Text Study: Language Development

One vital component of mature reading development that has been woefully neglected in national discussions of the Common Core Reading standards is targeted instruction in the actual language of informational text study. While sample complex text passages and related depth-of-knowledge questions are now widely available on the Internet, little to no concrete guidance is provided regarding the process of teaching students the language skills they will need to engage in competent academic interaction about text.

Teachers serving young, under-prepared readers, whether English learners or native English speakers, must factor in lessons that introduce students to the advanced language of informational text analysis. Students whose formal literacy instruction has been primarily based on literature do not have a portable toolkit of relevant terminology. Informational and narrative text features, organization, genres, comprehension questions, and constructed response tasks differ strikingly, as do the lexicons of these discrete fields of study. Neophyte readers of informational text benefit from a series of lessons aimed at familiarizing them with the terms they are apt to encounter in lesson material and assessments.

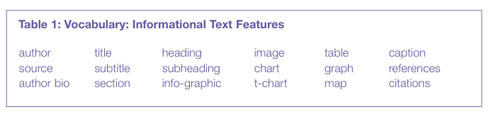

Before embarking upon a foray into an informational article, students must be introduced to the terms used to discuss informational text features. Years of experience working with recent immigrants and first-generation high school graduates in a university partnership have taught me the wisdom of launching an informational text unit with a meticulous walk-through of an article and chapter text features. Early in the school year, most of these aspiring scholars have limited experience independently and successfully completing an informational text and refer to any assigned selection as a “story.” I have therefore found it productive to provide my linguistically diverse high school freshmen with a photocopy of an article from a teen news magazine and a social studies chapter. I visibly display each page of the target text, highlight each distinguishing feature, and guide the students in labeling each feature (see Table 1). Terms such as source, section, subheading, table, caption and references aren’t routinely used in short stories or novels. Students need to observe and articulate the cohesive features of various informational texts, ranging from journal articles to textbook chapters, along with the unique features of specific text types. As an illustration, an article in a science research journal will contain a crucial summary and implications section, while a feature article in a weekly news magazine will not.

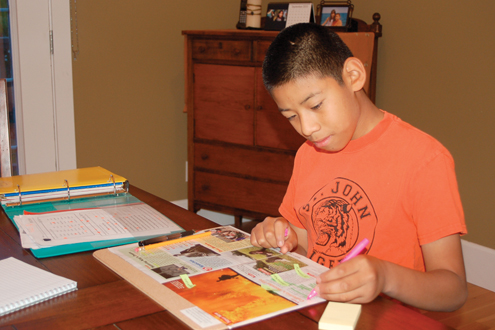

We can’t ask students to make predictions about text content using text features or prompt them to justify where they identified essential details if they have little formal understanding of the text structure and labels for each part. My own son, an English learner, is elated that his elementary English language arts coursework now includes a weekly news periodical, providing opportunities for him to learn about current events. For a recent homework assignment, however, he was flummoxed by the questions that required specifying the location of the evidence he obtained from the selection to support a claim. I grabbed a packet of sticky notes and helped him navigate the article, labeling each part, asking him to repeat the terms, and showing him the consistent features in subsequent articles within the periodical (see following image).

Providing a Reality Check about the Informational Text Reading Process

After equipping my nascent high school students with a working knowledge of an informational text’s structure and terms, I have a serious tête a tête with them about the level of complexity they will be encountering in independent course assignments, requiring multiple reads. For students who have come to rely on an enabling teacher to complete the assigned text, summarize the key ideas, and present notes that serve as the primary test content, this is a sobering prospect.

Preparing students for the reading demands of high school and college curricula involves a reality check about the time and process involved in maturely engaging with a text as an accomplished scholar would in any discipline. Modeling the process of previewing an entire text to gauge text complexity then breaking it down into manageable segments for detailed reading and study is essential support for developing readers. Under-prepared students have rarely learned the cognitive secrets of siblings or high-achieving students who have successfully managed tomes of content-area reading. They rely on their teachers to demystify the process of reading to learn and guide them in developing a consistent, productive process for tackling challenging assignments. Without explicit, interactive in-class guidance, ill-equipped readers plow into a research article as if they were approaching a short story, starting on page one, with no sense of the text length, focus, structure, or more essential sections, and rarely make it beyond the introductory matter.

Modeling the Process and Language of Informational Text Previewing

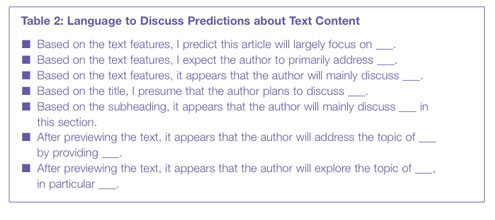

Having clarified that my course reading and writing tasks will focus on informational text selections, I model the process of text previewing with a goal of establishing the topic, focus, overarching structure, level of complexity, and time commitment for conscientious reading and study. Unless I provide my students with language forms to scaffold this interactive process and discussion, I can predict inappropriate casual responses like the following: “It’s gonna be about…,” “It looks hard,” or “Do we really have to read this?” The first phrase I introduce for our post-preview discussion of text content and structure is “Based on…,” an essential language tool for analysis of text features, claims, and supporting evidence. Table 2 includes an array of sentence frames that enable students to adeptly communicate their predictions and impressions of text content and complexity gleaned from the preview process.

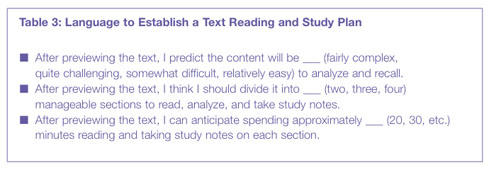

The ultimate goal of this process is ensuring that students are more familiar with the text architecture and content and are heading home with a viable reading and study plan. The frames in Table 3 serve as productive discussion starters for lesson partners and enlightening “exit slips” for teachers committed to serving as disciplinary literacy and language mentors.

Explicitly Teaching Language to Discuss Key Ideas in Informational Text

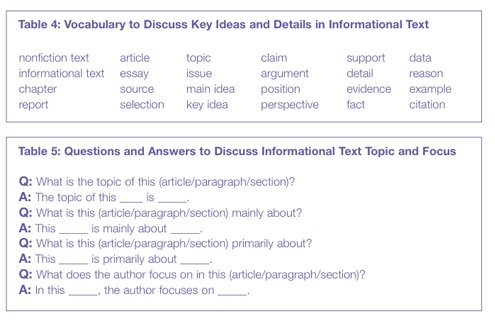

After modeling proactive text previewing with a goal of establishing a viable study plan, disciplinary reading mentors must turn their attention to explicitly teaching essential vocabulary to discuss the informational text content. To engage in academic interactions during lessons, students need a practical toolkit of terms to discuss informational text types, key ideas, and types of support that are rarely if ever used in narrative text analysis and response. Familiar literary terms such as character, theme, plot, and conflict have no bearing on informational text study.

In this digital information age, developing readers need to master labels for an eclectic array of text types, ranging from data-driven, objective texts such as scientific reports to highly subjective sources such as op-ed pieces and blogs. Curricular mainstays of upper-elementary and secondary coursework include chapters, articles, reports, and expository essays. In tandem with being able to articulate the type of text they are assigned and understanding its distinguishing features, students need an arsenal of vocabulary to discuss the most essential content. Table 4 offers a number of terms students benefit from learning and practicing to be able to correctly interpret questions and prompts used in informational text analysis and response tasks. For example, the terms claim, argument, position and perspective are often used synonymously. If we limit our discussion to a consistent term such as claim over a course of study, students are baffled when a test question instead utilizes the term position on an issue.

CCSS Listening and Speaking Emphasis on Competent Academic Interaction

One of the most pronounced CCSS shifts is the emphasis in the listening and speaking standards on collaborative interactions. On a daily basis, students are expected to engage in thoughtful and accountable interactions using appropriate language with partners, small groups, classmates and teachers during unified class discussions. During lessons with a text-based learning focus, neophyte collaborators are not likely to engage in articulate discussion without some targeted language preparation. Merely providing a litany of comprehension questions will not lead to stimulating discussion.

To make second-language acquisition gains, English learners must have daily opportunities to communicate using more sophisticated social and academic English.

However, assigned interactive activities without a carefully modeled process and established language goals, English learners focus more on “friendly discourse” than on producing and eliciting conceptually competent responses with linguistic accuracy (Foster & Ohta, 2005). Orchestrating peer interactions with clear roles, language targets, accountability for implementation, and meticulous monitoring ensures gains in oral language proficiency (Saunders & Goldenberg, 2010).

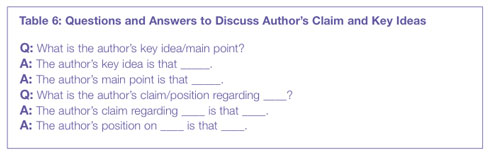

To prepare my classes for the linguistic demands of lesson interactions about text, I have found it extremely useful to prepare and distribute a “text discussion card” to prompt and facilitate appropriate questions and responses. I utilize heavy, brightly colored five-by-eight-inch card stock and print questions and response frames like those included in Tables 5 and 6. Initially, I introduce and practice this language with the unified class, using a series of more manageable and accessible texts. After ample practice over the course of two to three weeks, I can confidently establish small groups and assign text facilitation and discussion tasks. With the text discussion card as a reference tool, students can easily avail themselves of practical, relevant questions and response frames rather than having to turn their attention to displayed posters or draw exclusively from short-term memory. Students launch their collaborative analysis identifying the text focus and the author’s claim, before segueing to the key ideas and details in particular text sections.

Clarifying the Diverse Types of Support for Key Ideas

Prior to the launch of the CCSS reading standards, discussions of informational text in English language arts lessons across the grade spectrum have typically been few and far between and limited to the phrases main idea and important detail. In college coursework and professional discussions, scholars utilize a much more detailed and precise lexical bank to reference not only specific types of support for key ideas but also the degree of importance of particular details. An epiphany every young, capable content-area reader must have is that everything is not equally important in a concept- and data-driven informational text. That awakening must be complemented by the realization that the primary reading goal in disciplines such as science and social studies must be identifying what the author deemed most significant, not what the student found personally relevant.

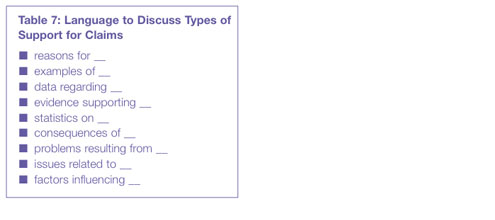

After previewing a lengthy text and breaking it down into manageable reading and study segments, a focused reader must embark upon a section in search of the author’s key idea and most significant support. Instead of asking young readers what is interesting and memorable in an evidence-based text, we must steer them in the direction of identifying what is most essential. There are arguably two vital aspects of vocabulary development that can help focus student analysis and discussion of essential support for key ideas. Table 7 provides a list of types of informational text support that are relevant to reading comprehension instruction as well as expository and argumentative writing. Authors justify arguments with a wide array of support, ranging from illustrative examples to convincing reasons. These commonly used secondary and post-secondary terms are included in Coxhead’s (2000) list of high-utility academic word families. Instead of having students simply name important details in a text section, we can prompt more adept and precise analysis by asking them to specify the kind of support provided. The question “How does the author support her claim regarding the hazards of texting while driving?” invites more mature analysis and articulate response, such as the following: “The author supports her claim with extensive evidence regarding increased fatal accidents.” This is more representative of college- and career-ready communicative competence than “She talks about more fatal accidents.”

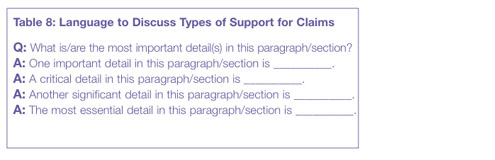

Once students have successfully identified the type(s) of support an author provides for a position or key idea, their next task it to separate the proverbial wheat from the chaff. Inexperienced content-area readers view all support as equally important and therefore benefit immensely from in-class coaching early in the school term on extracting the most essential text content from the less essential. Using accessible text exemplars to help students grasp the concept of more and less significant support, teachers can mediate this process using question and response frames like those included in Table 8. Academic adjectives such as critical and essential are not used frequently in literature study, but these high-utility academic terms (Coxhead, 2000) are lexical mainstays in verbal and written reports in the sciences and social sciences.

Concluding Remarks

The national focus in K-12 education on 21st-century literacy skills and career and college readiness holds great promise for students from every state. However, without a laser-like focus on explicitly teaching the competencies and requisite language for advanced reading, writing, and presentation, English learners and under-resourced classmates will be at a decided disadvantage as they approach rigorous performance-based assessments. If we are committed to providing an equitable arena for educational advancement and social mobility, we must strive as interdisciplinary colleagues across the grade levels to collectively demystify academic competencies and related language.

References

August, D., & Shanahan, T. (Eds.). (2006). Developing literacy in second language learners: Report of the national literacy panel on language-minority children and youth. Center for Applied Linguistics.

Carlo, M., August, D., & Snow, C. (2005). “Sustained vocabulary-learning strategies for English language learners.” In E. H. Hiebert & M. Kamil (Eds.), Teaching and learning vocabulary: Bringing research to practice (pp. 137-153), New York: Wiley.

Common Core State Standards (2010). Applications of Common Core State Standards for English language arts and literacy in history/social studies, science, and technical subjects. Retrieved from www.corestandards.org

Coxhead, A. (2000). “A new academic word list.” TESOL Quarterly 2: 213-238.

Foster, P., & Ohta, A. (2005). “Negotiation for meaning and peer assistance in second language classrooms.” Applied Linguistics 26(3) (September): 402–30.

Graves, M.F. (2000). “A vocabulary program to complement and bolster a middle grade comprehension program”. In B.M. Taylor, M.F. Graves, and P. van den Broek (Eds.), Reading for meaning: Fostering comprehension in the middle grades (pp. 116-135), Newark, DE: International Reading Association.

Kinsella, K. (2013). “Cutting to the Common Core: Making Vocabulary Number One.” Language Magazine, 12(12), 18-23.

Saunders, B., & Goldenberg, C. (2010). “Research to guide English language instruction.” In Improving education for English learners: Research-based approaches. California Department of Education.

Stahl, S.A. (1999). Vocabulary Development. Cambridge: Brookline.

Kate Kinsella, EdD (katek@sfsu.edu), is an adjunct faculty member in San Francisco State University’s Center for Teacher Efficacy. She provides consultancy to state departments of education throughout the U.S., school districts, and publishers on evidence-based instructional principles and practices to accelerate academic English acquisition for language-minority youths. Her numerous publications and programs focus on career and college readiness for academic English learners and under-resourced youths, with an emphasis on high-utility vocabulary development, informational text reading, and writing.