John Carr argues that the collaborative discussions element is the most important

of all standards

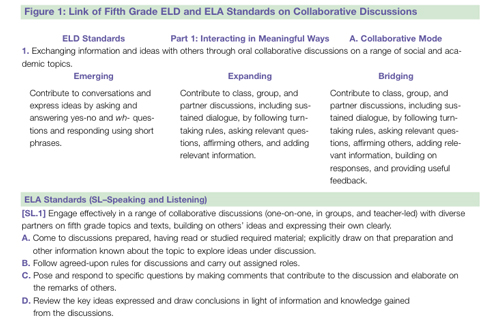

What is the most important standard among California’s English language arts (ELA) and English language development (ELD) standards? Sound arguments can be posited for many different standards. This article builds a case that contributing to collaborative discussions — the first ELD standard and first speaking-and-listening ELA standard — as a pair of linked ELD-ELA standards is the most important. Figure 1 presents these two linked standards for fifth grade in the format of an excerpt from a digital resource for teachers (Carr, 2014). Rigor of requisite skills appropriately and slightly decreases moving down to kindergarten and increases moving up to grades 11-12.

Collaborative Discussion is the Foremost Standard

The ELA standard specifies that collaborative discussions can be student pairs (one-to-one), in groups, and teacher-led. Working in pairs encourages the most contributions from each student, and triads can offer more perspectives or opinions while still engaging all three students. In groups of four or more, it is the English learners (ELs), whose English is emerging or beginning to expand, as well as students with learning disabilities who often are marginalized in collaborative activities and given low-level tasks and roles (e.g., draw a simple topical picture) in cooperative activities. To increase diversity of perspectives in a group discussion, each pair/triad can join another pair/triad in a two-step process of discussion and conclusion.

Students are expected to come prepared to contribute to discussions (ELA, SL.1A), which is easily identifiable as a college and career skill. For English learners (ELs), this may include prior teaching of high-utility academic words that are essential for understanding rigorous narrow reading units (Kinsella, 2013 and 2014). Teachers may also need to build ELs’ background knowledge, a key factor in reading comprehension, particularly for ELs who entered the U.S. at higher grade levels and for texts that assume the reader already has certain cultural and historical knowledge. For “dual-status ELs” — ELs who have a learning disability such as ADHD or “mild/moderate” autism, planning and organization skills can be very challenging and take many years to incrementally learn and become habitual (Carr and Bertrando, 2012). Teachers need to help these dual-status ELs be aware of and prepare for the next day’s collaborative discussion activity. The general education teacher might ask other staff about cultural or social learning issues for particular ELs and dual-status ELs and plan lessons appropriately. In an inclusive classroom, ideally a general education teacher with an ELD/SDAIE credential co-teaches with a special education teacher to ensure all students are engaged and learning during collaboration activities.

Looking at the next part of the ELA standard (SL.1B), students are expected to follow agreed-upon rules for discussions and carry out assigned roles. These skills are essential in many careers. The teacher must ensure that all roles are meaningful and prepare and support ELs and dual-status ELs to follow the rules (e.g., eye contact, acknowledge other perspectives, build on others’ ideas). As students grow in their social learning skills, one-minute quick idea sharing can move toward 15- to 20-minute time blocks for deep thinking and discussion.

In the last parts of the ELA standard (SL.1C and D), students are expected to pose and answer questions during the discussion and draw conclusions. This could be orally and/or in writing. Much of what has been said thus far can be effective and sustained when the pedagogy and professional development form a whole-school approach to teaching and learning (Calderón, 2014). Teachers who individually use collaborative discussions as the pivotal mode for student learning might feel overwhelmed teaching “in a silo” and give up over time when there is no collaboration among school faculty on certain common pedagogical practices. A student in a secondary school likely benefits the most from collaborative learning when it is an integral part of all classes during the day.

The Key to All ELD-ELA Standards

The ELD-ELA standard on collaborative discussions is the key to learning all other ELD and ELA standards. ELD Standard One is a necessary foundation for Standard Three, “offering and justifying opinions, negotiating with and persuading others in communicative exchanges.” An emphasis of the Common Core is the skill of argumentation communicated orally or in writing and discerning the soundness of arguments appearing in texts the student reads. When reviewing all of the standards, it is apparent how the standard on collaborative discussions is either part of or can be a scaffold for each standard. Collaborative discussions help struggling readers comprehend texts and struggling writers to form an outline or graphic organizer, particularly for argumentative ideas, to write an essay or report and use peer editing during the writing process.

The Key to Other Standards

The standard on collaborative discussions is like the axel of a wheel with spokes linked to all other standards.

To become a scientist or mathematician, students need to learn to talk like a scientist or mathematician, not merely read and write about topics and pass tests. The EL and dual-status EL may need to refer to discussion starters posted on the wall or in their binders as a scaffolds for contributing to the discussions and practicing academic discourse (for high school, “I hypothesize that…” and “Contrary to your opinion, I would argue that…”). Consider the following exchange between a math teacher and a high school student, an EL with a language-processing disability and dyscalculia (in short, difficulty thinking mathematically).

Student: I got the area of the rectangle by the lengths and widths.

Teacher: Do you mean you computed the area of the rectangle by multiplying the length by the width?

Student: That’s what I mean. I just didn’t use all the math words right like you did.

Among other things, the math teacher considers whether or not the student understands that the “social, nonacademic” words and and by have specific meaning as academic words in mathematics.

Struggling readers can be supported to comprehend rigorous texts and writers to communicate critical thinking, especially argumentative, and all students are likely to be much more engaging when collaborative discussions are a part of reading and writing tasks. Use of language should not be limited to interactions between teacher and student; it should be the foundation for participatory, social learning in peer groups.

The teacher strategically forms small groups, considering the goal, topic, and advantages of homogenous versus heterogeneous groups (Richard-Amato, 2001). A rule of thumb is not to place ELs who are more than one ELD level apart and no more than one student with a learning disability in the same group (Carr and Bertrando, 2012). The rule of thumb might be waived in certain situations, such as in a science class of all Spanish-speaking ELs in which a Spanish-bilingual teacher plans and supports bilingual academic language. In one small group, students blend the use of English and Spanish, such as by using terminology better expressed by one language or including the lesson’s key English vocabulary, and one student volunteers to translate as needed for a new emergent-ELD-level student to understand and express his ideas.

References

Calderón, M. (February, 2014). “Teaching Across the Board.” Topanga, CA: Language Magazine, 18-21.

Carr, J. (2014). Link of ELD-ELA Standards for California. Access at http://www.jcarrmaa.com/category-s/1817.htm.

Carr, J. and Bertrando, S. (2012). Teaching English Learners and Students with Learning Difficulties in an Inclusion Classroom. San Francisco: WestEd.

Richard-Amato, P. A. (2001). Making It Happen: From interactive to participatory language teaching (3rd Edition). White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Kinsella, K. (August, 2013). “Cutting to the Common Core: Making Vocabulary Number One.” Topanga, CA: Language Magazine, 18-23.

Kinsella, K. (April, 2014). “Cutting to the Common Core: The Benefits of Narrow Reading Units.” Topanga, CA: Language Magazine, 18-23.

John Carr is the founder of John Carr Educational Enterprise (JCEE, jcarrmaa.com), author of the Link of ELD-ELA Standards for California, and former lead author of the (outdated) Map of ELD-ELA Standards.