Nile Stanley and John Ronghua Ouyang encourage teachers to use the new literacies to inspire the next generation of multilingual filmmakers

Most prospective teachers and the pupils they will teach have been surrounded by constantly evolving information and communications technology (ICT) — computers, email, social networks, smartphones, and digital cameras — since preschool. The internet is this generation’s defining context for literacy and learning and requires new skills, strategies, and dispositions (Castek et al., 2007). Paradoxically, teacher candidates have lived a digitally saturated life, but many have not had the preparation in the new literacies of how to integrate ICTs in their multilingual classrooms. To support integration of the ubiquitous technology that surrounds us, literacy learning, and language acquisition, teachers should take a close look at what filmmaking projects have to offer (Stanley and Ouyang, 2013).

Much of the education literature (Figg and McCartney, 2010) has stressed that a major appeal of using filmmaking, also referred to as digital storytelling, is that it promotes the 21st-century skills needed to be successful in today’s global economy. Filmmaking and digital storytelling are similar processes and the terms are often used synonymously, but the former is more exclusive, requires more expertise, and uses more sophisticated cameras, lighting, and acting techniques, where often the emphasis is on creating spectacular special effects. Digital storytelling is more democratic — anyone with a cell phone is capable — and it focuses more on telling the story and less on the art of film. Filmmaking requires learners to become skilled communicators, critical thinkers with abilities that allow accessing, managing, integrating, and creating information with a variety of media. In this study, a filmmaking project focused on the development of documentaries that tell a factual story and convey compelling information in vivid and expressive ways for the public interest, much like an investigative journalist would do. Good filmmaking requires literacy skills, including reading, writing, and researching informational texts, and technological skills.

Much of the research on teacher candidates using filmmaking focuses on the positive impacts for a range of age groups and contexts. Figg and McCartney (2010), in their study of teacher candidates and their middle school students, found each of the candidates increased understanding of teaching with technology through participation in a project. The middle school students showed improvement in motivation, technical skills, vocabulary, and writing development. Filmmaking provided technologically enhanced field experiences for teacher candidates.

Hodge and Wright (2010) conducted two projects that investigated digital storytelling as a way to capture pre-service teachers’ learning in a social studies and a math methods course. The researchers gleaned a number of informative points from the projects. Digital storytelling provided thoughtful, inquiry-based learning in which candidates themselves actively created new knowledge instead of passively consuming information made by others. Digital storytelling enabled both candidates’ and the underrepresented community’s stories to be voiced as they learned to send messages around the world in English as well as in students’ home languages. Similarly, Sadik (2008) conducted a study to understand better and describe the impact on student learning when teachers and students take advantage of digital storytelling for their teaching and learning tasks in the subjects of English, math, social studies, and science.

Chen and Li (2011) were university English teachers in Taiwan who conducted an action research study of a semester-long filmmaking project to determine if it was an effective method for boosting students’ motivation for learning content and engaging in classroom activities. The survey results indicated that the filmmaking project turned out to be the most popular assignment for both students and instructor. There were many benefits of filmmaking. Students found filmmaking a more fun and efficient way to learn English over textbooks. Students produced films with titles like Why Study English, Sell Yourself, and Taiwan, Formosa. They felt in control of their learning. Learning in the class spilled out of the class, and students learned self-confidence and teamwork. Students learned to more broadly view literacy, beyond reading and writing. They came to appreciate the value of including the visual and audio as essential new literacies for succeeding in the modern world. One of the shortcomings was that some of the students were shy and timid in performing their stories in front of the camera.

We conducted an action research study to determine the impact of a filmmaking project in one undergraduate class, Methods and Materials of Teaching Literacy, focused on instructional strategies for teaching reading to elementary children grades K-5. The 21 participants included 20 females and one male, with an average age of 20. The pre-service teachers, also referred to as candidates, used Blackboard as an online learning platform, supplemented with face-to-face meetings. Initial survey results indicated most candidates had no or very limited filmmaking experience and none had previously produced a digital storytelling project.

Two graduate assistants on the project were film-major exchange students from China and Japan respectively. They had significant filmmaking experience and media skills including storyboard creation, filming, editing, and final production. The graduate students were unpaid volunteers for the project and highly motivated to become filmmakers as a career. The project afforded learners the opportunity to participate in cross-cultural literacy exchanges in multiple languages.

“We have limited media resources and no opportunities for independent filmmaking study with a professor in our countries. That we can participate in a film festival, learn skills to help us get jobs, and make real documentary films for a university are tremendous opportunities for us.” These remarks of a graduate student captured the enthusiasm and drive of the international students.

Their primary roles were to assist the instructor in producing promotional documentary films for the department’s recruitment campaign, assist with data collection in the project, and screen films at the World Arts Film festival (worldartsfilmfestival.org.) The festival’s stated purpose was “to support artists and filmmakers of all ages and of all abilities, including those with special needs, to create, inspire, and share their work with each other and the world.” The festival was held at the Modern Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in downtown Jacksonville, Florida, near the campus.

The filmmaking project duration was over a 14-week semester. In week three, the project was begun; in week ten, first drafts of films were due; final revised cuts were due week twelve; and final screening of the films was at the festival in week 13. The undergraduate candidates’ training in filmmaking was minimal. They received a one hour demonstration of how to use a Flip Video camera from an instructor of technology.

The instructors and graduate assistants provided two 15-minute demonstrations of producing two two-minute class productions “shout outs” where candidates did brief skits to introduce themselves. One artifact by undergraduates demonstrates a basic digital storytelling technique filmed with one camera and little editing (youtube.com/watch?v=cnESiOY6PaM).

The graduate students’ artifact demonstrates advanced filmmaking techniques using two camera angles with more sophisticated editing (youtube.com/watch?v=rgXcjUhPKog&feature=youtu.be).

The complete filmmaking process was modeled by the instructors, from storyboard creating to filming, editing, and posting on YouTube. The purpose was to launch participation in the upcoming film festival. The students were given a digital storytelling rubric as a guide to evaluating the quality of their films. They were instructed to make a five- to seven-minute documentary about some inspiring aspect of education. The students signed out one Flip Camera per group, no tripods; but they were encouraged to seek help from the Instructional Technology Lab if they needed assistance or had questions. Most of the assistance the students sought occurred at the end of the project, near the deadline for uploading the film to a digital dropbox. The majority of challenges the undergraduates faced were on how to edit video and upload the finished product using Movie Maker software. The films were evaluated by the two instructors and a film festival judge using the rubric. After a screening of the films at the festival, the candidates participated in a focus group with open-ended discussion to detail through flexible dialogue their perceptions and experiences regarding digital storytelling. It was filmed, with the participants’ permission, and analyzed by the instructors and graduate assistants.

Four undergraduate-student documentary films, which averaged in length from four to six minutes, were produced. The film titles were The Importance of Recess, Homelessness in Jacksonville, Changing Lives through Mentoring Refugee Families, ESOL Empowers International College Students, and The Jock Mentality. In The Jock Mentality, the undergraduates’ artifact demonstrates a basic digital storytelling technique. (youtube.com/watch?v=T56Qz3McV8E). This movie is based on the lives of college student athletes, who juggle a million things in one day, giving young students the message that anything is possible if they really try.

One film, made by a graduate assistant in collaboration with the instructor, was produced. In Hope at Hand, Inc., the graduate students’ artifact demonstrates advanced filmmaking techniques (www.youtube.com/watch?v=VOPTgtcLUKU). The film is about Hope At Hand, Inc., a nonprofit organization that provides art and poetry therapy to underserved children and adults in need.

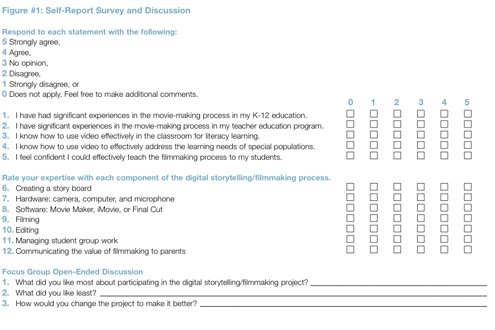

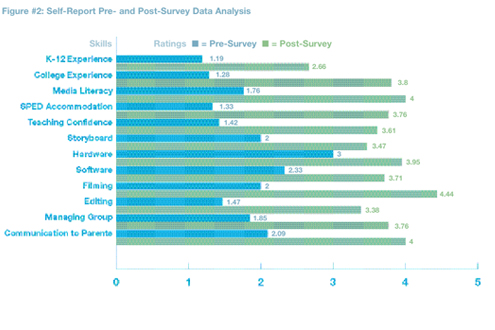

Filmmaking self-report pre- and post-surveys were used to assess participants’ skills by rating their expertise on a Likert scale with various media components. See Figure #1 for an example of the questionare that was used. Pre-service teacher candidates self-reported learner confidence scores on the pre- and post-surveys in Figure #2 were compared by using group means on a scale of 0 to 5. Scores above 3.5 were designated having acceptable confidence in one’s media ability. The results indicate that the digital storytelling approach exposed the candidates to new media literacies, which increased their confidence to infuse technology into their teaching in the media skill areas. At the beginning of the project, candidates reported having scant prior knowledge and experience with digital storytelling/filmmaking in their own public school (M=1.19) or college education (M=1.28). Candidates rated their ability to use media literacy effectively in the classroom, initially (Pre-M=1.78) and at the end of the project (Post-M=4.0). Candidates improved their own media literacy, as evidenced by increased confidence with the skills of filmmaking: storyboard creating, operating a camera, using editing software, and integrating sound, music, and pictures to tell a story. Participants overall gained insights about diversity accommodation and developed a connection to their community, with increased skill to communicate to parents about the value of technology.

Focus Group

The participants’ perceptions and experiences are summarized here. What they liked most about participating in the digital storytelling/filmmaking project was learning about the inspiring stories of diverse people within their community.

“I was really touched to learn about how volunteers are making positive impact for marginalized groups like the homeless and refugees within our community” was one comment by a participant.

The second-most-popular aspect of the project was the opportunity to increase ICT skills for teaching. According to one student, “I really feel confident now that I will be able to teach my students, the children, in how to make a film documentary. This is important that today’s youth understand how to use technology for learning. Definitely, I liked learning filmmaking by actually doing it, rather than just being lectured about it.”

In responding to the question “What did you like the least about the project?” the majority of comments centered on the time and demands of the project. “We spent hours and hours editing our film. We had to go to the tech lab several times for help.” “We had a hard time setting up interviews with the subjects of our documentary, because they kept cancelling and rescheduling.”

In regards to the question “How would you improve the project?” most of the participants expressed that they wanted more planning time for the project during class time. Meeting outside of class was difficult. They wanted more guidance in managing the group work that the project required. Some candidates were reluctant to embark on a filmmaking project and questioned its value for a number of reasons. For example, they did not see filmmaking as integral to teaching literacy skills. They did not see much filmmaking teaching taking place in the local public schools. The emphasis of instruction is teaching to the high-stakes test. They were concerned that filmmaking would take away too much time from the mandated curriculum. They were concerned that when they began teaching, the school would not have the necessary media resources for filmmaking, such as enough cameras and editing software. They were concerned parents would object to their children making films. Future filmmaking projects should focus on “buy-in” — that is, why learning technological skills is important for teaching.

Conclusion

Filmmaking offered a way for educators to integrate ICTs the new literacies, build cross-cultural collaboration, and help students blend personal empowerment with community responsibility. The digital storytelling approach with a service learning component of participating in a film festival exposed the candidates to new media literacies, which increased their confidence to infuse technology into their teaching in the media skill areas. Participants improved their own media literacy, as evidenced by increased confidence with the skills of filmmaking. The participation of international exchange students was mutually beneficial to the learners themselves and the institution.

References

Castek, J., Leu, D. L., Coiro, J., Gort, M., Henty, L.A., Lima, C.O. ( 2007). “Developing new literacies among multilingual learners in elementary grades.” In L. Parker (ed.) Technology-mediated learning environments for young English learners: Connections in and out of school. (111-153). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erbaum Associates. Retrieved on September 4, 2013 from www.newliteracies.uconn.edu/pubs.html.

Cheti, C. & Li, K. (2011). “Action! – Boost students’ English learning motivation with filmmaking project.” Journal of Educational Technology Development and Exchange, 4(1), 71-80.

Figg, C., & McCartney, R. (2010). “Impacting academic achievement with student learners

— Teaching digital storytelling to others: The ATTCSE digital video project.” Contemporary Issues in Technology and Teacher Education, 10(1). Retrieved from

http://www.citejournal.org/vol10/iss1/languagearts/article3.cfm.

Hodge, L.L., & Wright, V. H. (2010). “Using digital storytelling in teacher learning: Weaving together common threads.” Journal of Technology Integration, 2 (1), 25-37.

Sadik, A. (2008). “Digital storytelling: A meaningful technology-integrated approach for engaged student learning.” Education Technical Research and Development, 56, 487-506 DOI 10.1007/s11423-008-9091-8

Stanley, N., & Ouyang, R. (2013). “Using digital storytelling, filmmaking and cross-cultural collaboration to improve online distance learning.” Paper presented at the 25th Conference of the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE). Tianjin Open University, China.

Stanley, N., & Dillingham, B. (2011, February). “Making learners click with digital storytelling.” Language Magazine, 10 (6) 24-29. Retrieved on September 4, 2013 from http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Hazzard-MakingMovies.html.

Dr. Nile Stanley, nstanley@unf.edu, is an associate professor of elementary education, and Dr. John Ronghua Ouyang, ronghua.ouyang@unf.edu, is a professor of educational technology, childhood education literacy, and TESOL at the University of North Florida, Jacksonville.