Stephen Krashen with an inexpensive, simple approach to closing the equity gap in literacy

“Doctors, nurse practitioners, and other medical professionals incorporate Reach Out and Read’s evidence-based model into regular pediatric checkups, by advising parents about the importance of reading aloud and giving developmentally-appropriate books to children.” (reachoutandread.org).

Reach Out and Read (henceforth ROR) is a simple and inexpensive program. While in waiting rooms for well-child pediatrician’s appointments, hospital staff shows parents reading activities they can do with their children, with a focus on reading aloud to the child, and discusses the importance of reading, which the physician does as well. The families receive free books at each doctor visit. ROR is typically aimed at lower-income groups.

Departing from traditional academic style, I present first the results of ROR evaluations, focusing on the impact of ROR on vocabulary development. I will then try to make the point that ROR is a modest and inexpensive intervention; even though “more ROR” appears to produce better results, vigorous interventions are small-scale. Finally, I note that the crucial component of ROR appears to be reading aloud to children, a practice that already has an excellent track record (Trelease, 2006). The implication is that these simple approaches deserve more attention.

Positive Impact on Vocabulary Development

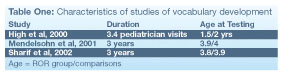

The ROR website (reachoutandread.org) includes three evaluations in which children were tested on their acquisition of vocabulary (table 1). The design of two of the studies (Mendelsohn et al. and Sharif et al.) is nearly identical, with children tested at about 4 years of age after three years of experience with ROR.

Families in all three studies were low-income. Subjects in Mendelsohn et al. were characterized as “poor and undereducated with a preponderance of Latino immigrants” (p. 131) who had come to inner-city pediatric clinics for “routine well-child care.” Participants in Sharif et al. attended pediatric clinics in the Mott Haven section of the South Bronx, “the poorest congressional district in the United States” (p. 172). Participants in the High et al. study were described as “multicultural, low income families.” In Sharif et al. and Mendelsohn et al. a significant percentage of the families were Spanish-speaking and interviews, orientation and testing were done in Spanish when families preferred it.

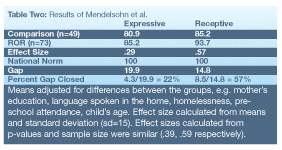

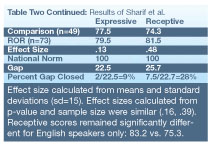

Two studies (table two) used identical measures, the Expressive and Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary tests. Test scores were standardized for age (100 = 50th percentile). In both studies, children were at a similar age when tested, and durations of treatment were similar. In both cases, ROR children did better on the vocabulary measures and the ROR advantage was larger on receptive than expressive vocabulary tests. In Sharif et al, however, the difference between the ROR and comparison groups was not statistically significant for the expressive test (p = .26).

Because all subjects were from low socio-economic families, it is not surprising that the children scored below the national median (100). The ROR children, however, closed from about one-fourth to one-half of the gap on the receptive test (table two).

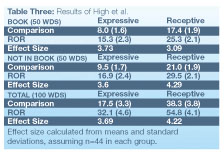

High et al. used a modified version of a standardized test, the MacArthur Communicative Developmental Inventory, testing both expressive and receptive vocabulary. One part of each test contained 50 words that appeared in the books that were distributed and one part contained 50 words that did not appear in the books that were distributed. As the children in this study were very young, the children themselves were not tested but parents were asked if the child could produce or understand the words.

The data in table three presents only the results for children who were between 1.5 to 2 years old at the time of testing (n = 88). For children ages 13 to 17 months, the ROR children were slightly but not significantly better in receptive vocabulary and the comparisons were better in expressive vocabulary, with the difference approaching significance. For the older children, however, the ROR group was clearly better, both for words appearing in the books and words not appearing in the books. The superiority of the ROR children for words not appearing in the books suggests that parents brought in other books for the children (see discussion of Theriot et al. below).

Golova et al. (1999) used a similar measure and obtained similar results, finding no difference in vocabulary with children under 18 months at the time of testing, but a trend for ROR children older than 18 months to do better, with the difference reaching statistical significance for receptive vocabulary. Golova et al. did not provide details, however.

Fortman et al. (2003) reported no impact of ROR in middle class families. The positive impact of ROR may be limited to low-income families, those with less access to books and less likely to read to their children.

A modest treatment

The data present above shows that a modest and inexpensive intervention produced consistent results in vocabulary development in three separate studies. The entire treatment consisted of a few well-child pediatrician visits, providing some information about reading aloud to children, and providing a small number of books. For example, over a three-year span, subjects in one study (Mendelsohn et al.) had an average of only three well-child appointments in which their doctors discussed books and received an average of four books.

Of course there are limits as to how modest Reach out and Read can be and still be effective. Merely providing information or a book just once (during an emergency room visit) has not been shown to have an effect on family reading practices (Nagamine et al.

2001). Providing additional books, either through physician visits or parents’ buying books, results in better gains in vocabulary (Theriot et al), and the combined effect of books and information-providing sessions is very strong.

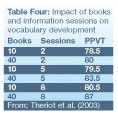

Theriot et al. examined the impact of books provided by parents (in addition to those given by ROR; the average number of ROR books was five) and the number of information sessions parents attended on vocabulary development. The children were three years old and had been involved with ROR since they were two months old. With only few books available (10), more information sessions resulted in a modest increase in performance on a receptive vocabulary test (PPVT). But when more books were available (40), a similar increase in sessions had much larger impact (table four).

The maximum treatment in Theriot et al., 40 additional books and eight sessions, is still a modest intervention. It is also noteworthy that the difference between children with the fewest books and sessions and those with the most was about 10 points, or 2/3 of a standard deviation (sd = 15), an effect size of about .67, similar to the advantage seen of ROR in general over comparison groups on receptive vocabulary tests (table two).

The importance of Read-Alouds

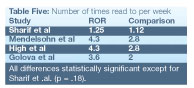

As mentioned earlier, ROR information sessions include encouragement of and information about reading aloud to children. Studies of the impact of ROR consistently show that ROR children are read to more than comparison children (table five).

The crucial role of read-alouds was confirmed by High et al.’s analysis (High et al., 2000) showing that frequency (days per week) of read-alouds was a strong predictor of scores on both vocabulary measures, controlling for demographic variables, including parental language proficiency. In fact, when frequency of read-alouds was considered, High et al. reported that participation in ROR had no additional impact on vocabulary test performance. These results are consistent with research showing the positive impact of read-alouds on literacy development (Bus, Van Ijzendoorn and Pellegrini. 1995; Blok, 1999) and in stimulating interest in reading (Brassell, 2003; Trelease, 2006; Wang and Lee, 2007; Cho and Choi, 2008).

The results also suggest that the impact of additional books and information sessions, as demonstrated by Theriot et al., was due to increased reading aloud to the children.

Discussion

ROR (or more properly, RORA, for Reach Out and Read Aloud) has been shown to increase the frequency of reading aloud in low-income families and results in substantial gains in vocabulary, especially in receptive vocabulary. It requires only a modest investment in time and material (books), but results so far indicate that it can substantially help close the equity gap in literacy, the difference in literacy competence between children from high and low-income families.

This is a contrast to the much more expensive and elaborate solutions currently under consideration, thus far lacking in clear empirical support (e.g. The LEARN Act, see Krashen, 2010). The results also mean that we need to pay more attention to the obvious and well-attested means of increasing literacy, read-alouds (Trelease, 2006), and continue to study the effects of ROR as well as similar projects (e.g. Imagination Literacy and Book Trust,* the latter providing books to older children. It also means reversing the current trend of defunding libraries, a major source of books for readers of all ages.

References

Blok, H. 1999. “Reading to Young Children in Educational Settings: A Meta-Analysis of Recent Research” Language Learning 49 (2): 343-371.

Brassell, D. 2003. “Sixteen Books Went Home Tonight: Fifteen Were Introduced by the Teacher” The California Reader 36 (3): 33-39.

Bus, A., M. Van Ijzendoorn, and A.Pellegrini. 1995. “Joint Book Reading Makes for Success in Learning to Read: A Meta-Analysis on Intergenerational Transmission of Literacy” Review of Educational Research 65: 1-21.

Cho, K. S., and D. S. Choi. 2008. Are Read-Alouds and FreeReading “Natural Partners”? Knowledge Quest 36(5): 69-73.

Fortman, K., Fisch, R., Phinney, Defor, T. 2003. “Books and Babies: Clinical Based Literacy Programs” Journal of Pediatric Health Care 17: 295-300.

Golova N., Alario A., Vivier P., Rodriguez M., and High P. 1999. “Literacy Promotion for Hispanic Families in a Primary Care Setting: A Randomized Controlled Trial” Pediatrics. 103: 993-997.

High P., LaGasse L., Becker S., Ahlgren I., and Gardner A. 2000. “Literacy Promotion in Primary Care Pediatrics: Can We Make a Difference?” Pediatrics. 104: 927-934.

Krashen, S. 2010. “Comments on the LEARN Act” http//www.sdkrashen.com

Mendelsohn A., Mogiler L., Dreyer B., Forman J., Weinstein S., Broderick M., Cheng K., Magloire T., Moore T. and Napier C. 2001. “The Impact of a Clinic-Based Literacy Intervention on Language Development in Inner-city Preschool Children” Pediatrics 107(1): 130-134. Nagamine, W., Ishida, J., Williams, D., Yamamoto, R., and Yamamoto, L. 2001. “Child Literacy Promotion in the Emergency Clinic” Pediatric Emergency Care 17(1):19-21.

Sharif I., Rieber S., and Ozuah P.O. 2002. “Exposure to Reach Out and Read and Vocabulary Outcomes in Inner City Preschoolers” Journal of the National Medical Association. 94: 171-177.

Theriot J., Franco S., Sisson B., Metcalf S., Kennedy M. and Bada H. 2003. “The Impact of Early Literacy Guidance on Language Skills of 3-Year-Olds” Clinical Pediatrics 42: 165-172.

Trelease, J. 2006. The Read-Aloud Handbook. New York: Penguin. Sixth Edition.

Wang, F. Y., and S. Y. Lee. 2007. “Storytelling is the Bridge” International Journal of Foreign Language Teaching 3(2): 30-35.

Stephen Krashen currently serves as a member of the Board of Directors of Book Trust (Fort Collins, Colorado). All members of the Book Trust board serve without pay.