Richard Lederer gives us a sesquicentennial look back at the Gettysburg Address

“Abraham Lincoln wrote the Gettysburg Address while traveling from Washington to Gettysburg on the back of an envelope,” once wrote a student. In one fell swoop — and one swell foop — that young scholar managed to misplace a modifier and perpetuate an inaccurate myth.

In his Pulitzer-Prize-winning Lincoln at Gettysburg, Garry Wills dulls the old saw that claims Lincoln, divinely inspired, dashed off his speech during a brief train ride: “These mythical accounts are badly out of character for Lincoln, who composed his speeches thoughtfully. His law partner, William Herndon, observing Lincoln’s careful preparation of cases, records that he was a slow writer who liked to sort out his points and tighten his logic and his phrasing. That is the process vouched for in every other case of Lincoln’s memorable public statements. It is impossible to imagine him leaving his speech at Gettysburg to the last moment.”

From July 1 through July 3, 1863, at the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Americans slew Americans in the most lethal battle ever fought on U.S. soil. In that most pivotal clash of the Civil War, more than 51,000 soldiers were killed, wounded, or reported missing.

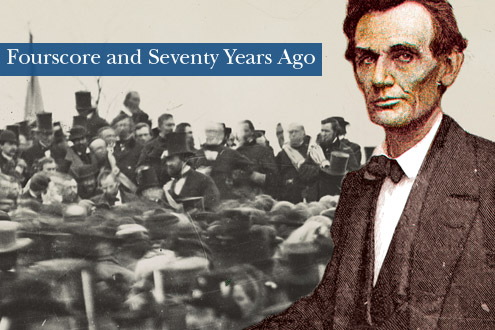

Four and a half months later, on Nov. 19, 1863, a crowd of about 15,000 gathered at Gettysburg to consecrate a new Civil War cemetery. Most of us are unaware that the real Gettysburg Address was delivered that day by the featured speaker on the program, Edward Everett of Massachusetts, the nation’s most celebrated orator. The speech that Lincoln spoke that Thursday afternoon was listed as “Dedicatory Remarks by the President of the United States.” Those remarks were intended as a brief and formal follow-up to Everett’s two-hour oration dedicating the opening of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg.

The story’s headline in the New York Times makes clear who was the designated declaimer of the day:

IMMENSE NUMBERS OF VISITORS

Oration By Hon. Edward Everett

Speeches of President Lincoln,

Mr. Seward and Governor Seymour

What happened at Gettysburg was that with 270 fateful words and but ten sentences, Abraham Lincoln articulated “a new birth of freedom.” Within the brief compass of less than three minutes, a weary President gave a young nation a voice to sing of itself. Afterward, Edward Everett took Lincoln aside and said, “My speech will soon be forgotten; yours never will. How gladly would I exchange my hundred pages for your twenty lines!”

The Gettysburg Address is the most memorized speech in the world. The very brevity of Lincoln’s text rendered it more luminous, more universal, and more memorable. That compactness allowed hundreds of newspapers to print the text and countless schoolchildren yet unborn to memorize it. The IRS Form 1040 EZ contains 418 words and the back of a Lay’s potato chips 401. With just 272 words, President Lincoln transformed a gruesome battle into the raison d’etre of a truly United States that for the first time in its history became a union. Before Lincoln, people used “the United States” as a plural: “the United States are…” Ever after it would be “the United States is…” Abraham Lincoln had forged not only a creed of democracy, but also, in the words of Carl Sandburg, “the great American poem.”

Sevenscore and ten years ago, on that brisk, sunny day in Pennsylvania, Lincoln said, “The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here.” In that, he was mistaken. The world at once noted what he said there and has never ceased remembering.

Richard Lederer, MAT English and education, PhD linguistics, is the author of more than 40 books on language, history, and humor. This excerpt is from his latest book, Amazing Words, a career-capping anthology of bedazzling, beguiling, and bewitching words, available now at his website — http://www.verbivore.com.