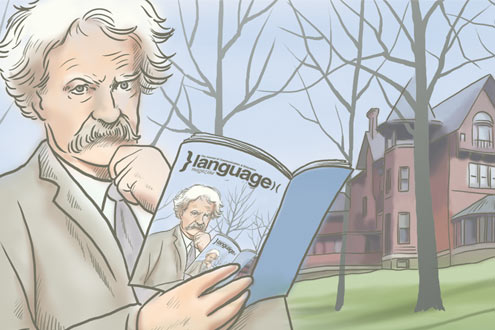

This year marks a century since the death, on April 21, 1910, of the most American of American writers, Mark Twain. On the night before that passing, Halley’s Comet shone in the skies as it made its closest approach to the earth. Just a year before, Mark Twain had said to a friend: “I came in with Halley’s Comet in 1835. It is coming again next year, and I expect to go out with it… The almighty has said, no doubt, ‘Now here go these two unaccountable frauds; they came in together, they must go out together.’ Oh! I am looking forward to that.”

In My Mark Twain, published the year after his dear friend’s death, William Dean Howells wrote, “Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, Holmes — I knew them all — sages, poets, seers, critics, humorists; they were like one another and like other literary men; but Clemens was sole, incomparable, the Lincoln of our literature.”

Just as Abraham Lincoln helped forge our identity as a truly united United States, Mark Twain gave a young nation a voice to sing of itself. His stories and essays are suffused with an unalloyed American folk poetry freed from the straitjacket of literary prose. Twain wrote in his notebook, “My works are like water. The works of the great masters are like wine. But everyone drinks water.” Has any other writer ever tapped as deeply the easy grace and direct simplicity of American speech?

Twain held strong opinions about a passel of subjects, and he possessed the gift of being able to state these views in memorable ways: “It’s better to keep your mouth shut and appear stupid than to open it and remove all doubt.” “Be careful about reading health books. You may die of a misprint.” “It’s easy to give up smoking. I’ve done it many times.” He also had a lot to say about style, literature, and the American language that he, more than any other writer, helped to shape:

On American English, compared with British English. The property has gone into the hands of a joint stock company, and we own the bulk of the shares.

On dialects. I have traveled more than anyone else, and I have noticed that even the angels speak English with an accent.

On choosing words. The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter — ’tis the difference between the lightning-bug and the lightning.

More on word choice. A powerful agent is the right word: it lights the reader’s way and makes it plain. A close approximation to it will answer, and much traveling is done in a well-enough fashion by its help, but we do not welcome it and rejoice in it as we do when the right word blazes out at us. Whenever we come upon of these intensely right words in book or a newspaper, the resulting effect is physical as well as spiritual, and electrically prompt. It tingles exquisitely around through the walls of the mouth and tastes as tart and crisp and good as the autumn butter that creams the sumac berry.

On style. (In a letter to a twelve-year-old boy). I notice that you use plain, simple language, short words, and brief sentences. That is the way to write English — it is the modern way and the best way. Stick to it; and don’t let fluff and flowers and verbosity creep in.

On Adjectives. When you catch an adjective, kill it. No, I don’t mean utterly, but kill most of them — then the rest will be valuable. They weaken when they are close together. They give strength when they are wide apart.

On using short words. I never write metropolis for seven cents when I get the same for city. I never write policeman because I can get the same for cop.

On the first-person-plural pronoun. Only presidents, editors, and people with tapeworms ought to have the right to use the editorial we.

On clichés. Adam was the only man who, when he said a good thing, knew that nobody had said it before him,

On grammar. Perfect grammar — persistent, continuous, sustained — is the fourth dimension, so to speak. Many have sought it, but none has found it… I know grammar by ear only, not by note, not by rules. A generation ago I knew the rules — knew them by heart, word for word, though not their meanings — and I still know one of them: the one which says — which says — but never mind, it will come back to me presently.

On spelling reform. Simplified spelling is all right, but, like chastity, you can carry it too far.

On literature. A classic is something that everyone wants to have read, but nobody wants to read.

On reading. The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can’t read them.

On dictionaries. A dictionary is the most awe-inspiring of all books; it knows so much… It has gone around the sun, and spied out everything and lit it up.

Richard Lederer, M.A.T. English and Education, Ph.D. Linguistics, is the author of more than 30 books on language, history, and humor. This excerpt from the upcoming Richard Lederer collection, A Treasury for Teachers, to be published October 2011. Explore his web site www.verbivore.com. Write him at richard.lederer@pobox.com.

Illustration by Amane Kaneko