Richard Lederer shares horrific, but true examples of miscommunication

The Crimean War (1853-1856) pitted the combined might of Great Britain, France, Turkey, and Sardinia against Russia. At stake were control of the holy places of Jerusalem and the strategic importance of the Crimean peninsula to the commerce and politics of the Black Sea.

At the Battle of Balaclava, on October 25, 1854, the heaviest British losses were the result of a futile attack by the 670 men of a gallant light cavalry brigade. The carnage was devastating, and the travesty and tragedy are immortalized in Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade.”

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismayed?

Not though the soldiers knew

Someone had blundered:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the Valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

“Someone had blundered.” The nature of the blunder was a confusion about one word that meant one thing to the speaker but another to the receivers of his commands. Fitzroy James Henry Somerset, Lord Raglan, commander of the British forces, gave the order to “charge the guns.” The guns to which he referred were an isolated battery over a slight rise in the valley, in plain sight from his vantage point. The only guns visible to James Thomas Brudenell, Earl of Cardigan and leader of the Light Brigade, were those of the tightly secured Russian battalion at the far end of the valley. The command seemed utter madness, but it was a command. While Raglan and his staff watched from behind the lines, Lord Cardigan dutifully led the charge into the Valley of Death. More than two-thirds of his men were killed or wounded.

That such a failure to communicate could result in the deaths of hundreds of soldiers is appalling, but evidence exists that World War II was extended by a deadly three weeks because of a single error in translation.

Victory in Europe for the Allies came on May 8, 1945, and Japanese resistance on the island of Okinawa ended seven weeks later. On July 26, 1945, Churchill, Stalin, and Truman issued the Potsdam Declaration: Japan had to surrender unconditionally or accept the consequences.

The Japanese cabinet seemed to favor a settlement but had to overcome two major obstacles to compliance — the tenacity of the Japanese generals and the pride of the citizens of Japan. Needing time, Japanese premier Kantaro Suzuki, on behalf of the Imperial Cabinet, issued a statement explaining that they were giving the peace offer mokusatsu.

Mokusatsu can mean either “We are considering it” or “We are ignoring it.” Most Japanese understood that the reply to the surrender ultimatum contained the first meaning, but there was one notable exception. The man who prepared the English-language translation for the Domei News Agency used “ignore” in the broadcast monitored by the English-speaking press. To lose face by retracting the news release was unthinkable to the proud Japanese. They let the statement stand.

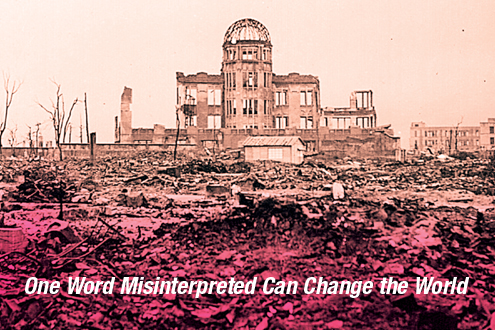

Believing that their proposal had been ignored or rejected and unaware that the Japanese were still considering the Potsdam Declaration, the Allies proceeded to open the atomic age. On July 28, 1945, American newspapers printed stories that the Japanese had ignored the peace offer, and on August 6 — 70 years ago — President Harry Truman ordered an atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. A new era in human history was irrevocably begun.

The destructive power of the bomb was an emblem of the destructive potential of language misused and misunderstood. The dead and missing from the bombing of Hiroshima numbered 92,000. Another 42,000 victims were claimed three days later by the blast at Nagasaki. Concurrently, Russia declared war on Japan and invaded Manchuria.

In the 20 days that followed the confusion about the meaning of mokusatsu, more than 150,000 men, women, and children were lost. One word misinterpreted.

Richard Lederer, MAT English and education, PhD linguistics, is the author of more than 50 books on language, history, and humor — available at his website — www.verbivore.com.