John Carr offers strategies for identifying and serving the growing population of English learners with learning difficulties

In the 2012-2013 school year, there were approximately 1,346,000 English learners (ELs) in California’s K–12 public education system (California Department of Education, 2013). It is estimated that, in general, 15% of students should qualify for special education services (Root, 2010), so it is likely that 202,000 students in California have or should have the dual status of ELs with a learning disability (EL-LD).

It can be difficult to distinguish between permanent language-learning problems, the normal second-language-learning process, but using the old deficit model and waiting years to document too little progress, and then responding is not the answer. This article provides guidance about how to informally assess ELs for an LD and then use the data and literature about what works to design a way for all diverse learners in the classroom to be successful learning the English language and content within a response-to-intervention (RTI) framework. Ideally, ELs and EL-LDs are served in inclusive classrooms in which co-teaching is often used.

I prefer the term “learning difficulty” to “learning disability,” because these students are able to learn but face challenges that neurotypical students do not. This article considers students with ADHD, mild to moderate autism/Asperger, and “specific learning disabilities” that include communication difficulties.

Commonalities among ELs and Students with LDs

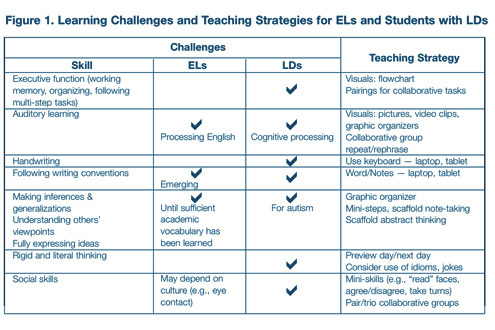

A common strength among many students with LDs is learning visually. The use of visuals also scaffolds auditory English language processing for ELs, especially at the emerging and expanding ELD levels (Carr and Bertrando, 2012). Challenges that tend to be common among ELs and students with one of the more prevalent LDs such as specific learning difficulty (particularly language-processing), ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder), and autism are presented in Figure 1.

An EL may have difficulty when key academic vocabulary is unknown or the “teacher talk” is long and includes many complex sentences. A student with an LD such as auditory processing may not process the meaning of words as fast as they are spoken, resulting in missing information and misconceptions (e.g., “A bee is an insect; therefore, it is not a subcategory of mammal”). A student with autism who may not be an EL may have difficulty with comparison words (e.g., “and/or,” “but/in contrast”), especially in the context of abstract ideas, as well as general difficulty thinking critically. The common rule of thumb is to give an EL about seven seconds to process a question; this might need to be extended for an EL-LD who is challenged to process the language, think critically, and express an answer.

Tony, a twelfth-grade EL-LD with autism and auditory processing difficulty, sat blankly when asked several “quick clarifying questions” that did not follow the order of ideas in his written report. Later, he said, “I knew the answers but I was very nervous. It was like I knew all the toys in my toy box but it spilled over and I couldn’t find each of the toys when the teacher asked.” This was Tony’s way of saying he had difficulty quickly accessing the information stored in his memory.

As ELs progress from emerging to expanding to bridging ELD levels (California’s new three ELD levels), they tend to use greater complexity in discourse and greater command of conventions. However, an EL-LD may have difficulty progressing through levels; for instance, the student may continue to make certain oral errors such as subject-verb agreement or auxiliary + main verb tense (e.g., “did went” instead of “did go”).

Flowchart of Assessment and Interventions

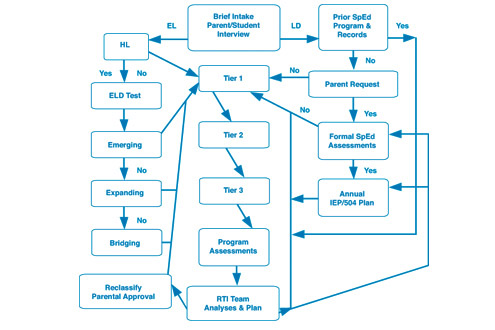

Figure 2 presents a system of instructional program decisions that reflects a common RTI framework for all students. For new students, a brief intake interview of the adult and/or high-school-age student is used to identify whether or not the student might be an EL and/or have an LD. Parents have a wealth of information that can assist educators.

During the intake interview, the Home Language Survey is used to determine if the state-approved ELD test should be administered. Designating a student as emerging, expanding or bridging, overall and in reading, writing, and speaking and listening, starts the process of determining the most appropriate ELD program for an EL (left side of Figure 2). The Learning Disabilities Checklist (National Center for Learning Disabilities, 2011) can serve as a guide (not a tool) toward determining if the student has an LD. If there is proof or suspicion that that student has an LD, special-education records should be requested from the previous school and/or the parent can request a new assessment (right side of Figure 2). This process for EL and LD identification can be greatly simplified and accelerated for students with accessible electronic records.

It is critical that the school psychologist who administers assessments to ELs for special-education services have expertise in linguistic and cultural differences, second-language development, and selecting and interpreting appropriate assessments. Far too few have that expertise (Klingner and Artiles, 2003). Comparing results of English- and native-language assessments can be helpful, but testing in two languages is not helpful if the student is bilingual and when the testing time exhausts the student.

During the year, teachers frequently assess students, monitor progress, collaborate with peers and parents, and try new instructional strategies that may be more effective. The school’s RTI team (DeRuvo, 2010) meets often (e.g., every four to six weeks) to monitor all students’ progress, and the programs and strategies being used and to determine if a student needs a change in Tier 1 (research-based classroom instruction) and/or Tier 2 (small group) or Tier 3 (individual or special education services) interventions. Tier 2 and 3 interventions can be delivered in the regular classroom, a push-in rather than a pull-out model.

When reviewing a student’s strengths and challenges, a teacher, or RTI or IEP team, should consider whether or not the observed characteristics or behaviors are typical for ELs or for students with a particular LD. A team that includes ELD and special-education teachers is the best way to assess an EL who may have an LD and to understand the whole child (Abrams, Ferguson & Laud, 2001). Sometimes, a strength can be a key that unlocks a challenge. An EL may find learning English phonics frustrating when “rules ar broken,” whereas a student with autism may show frustration because of having a very “rigid mind” in which unexpected changes are intolerable.

Using EL and psychological assessments in parallel and a common RTI framework for data-based instructional decisions, as shown in Figure 2, can have many benefits for school staff, students, and parents. While each student is unique, certain instructional strategies can effectively support the needs of many diverse learners in the general-education classroom.

Two Foremost Instructional Strategies

Two evidence-based instructional strategies that can benefit all students and particularly ELs and students with LDs are visuals and Think-Pair-Share (Carr and Bertrando, 2012; Hill and Flynn, 2006; Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001; Scruggs et al, 2009).

Visuals, the first strategy, include pictures, illustrations, video clips, and graphic organizers and support oral instruction when used in tandem throughout a lesson on a daily basis. Teachers can use graphic organizers to relate the past lesson and personal examples to the present topic and to organize information by categories and relationships. The teacher can use the following, second strategy to engage students in thinking about what should be entered into the graphic organizer.

Think-Pair-Share, the second strategy, provide pairs of students perhaps one minute for a structured discussion followed by a few minutes for pairs to share ideas with the whole class. This is an excellent strategy to support academic English language development for ELs and social learning skills for students with LDs. The strategy directly addresses California’s English language arts speaking and listening standard 1 and ELD standard 1, which involve collaborative discussions and are pivotal to all other standards.

Consider how to integrate visuals and Think-Pair-Share for a possible synergistic effect. For instance, at the start of a new unit lesson topic, a teacher could use Think-Pair-Share to give students time to think about and discuss information they already know in pairs for one minute. The teacher could then ask the whole class for ideas to enter into a visual such as a graphic organizer or KWL chart (what you know, want to know, have learned). Repeat the two-step process at key points throughout the lesson to add new information to the graphic organizer and adjust for prior misconceptions (especially for inquiry-based science lessons).

References

Abrams, J., Ferguson, J., & Laud, L. (2001). “Assessing ESOL students.” Educational Leadership, Understanding Learning Differences, 59(3), 62-65.

Carr, J. and Bertrando, S. (2012). Teaching English learners and students with learning difficulties in an inclusive classroom. San Francisco: WestEd.

California Department of Education (2013). California language Census: Spring 2013. Source is http://www.cde.ca.gov/ds/sd/cb/cefelfacts.asp.

DeRuvo, S. L. (2010). The essential guide to RTI: An integrated, evidence-based approach. San Francisco: WestEd and Jossey-Bass.

Hill, J. D., & Flynn, K. M. (2006). Classroom instruction that works for English language learners. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Klingner, J. K., and Artiles, A. J. (2003). “When should bilingual students be in special education?” Educational Leadership, Teaching All Students, 61(2), 66-71. (Article may be found online at ascd.org.)

Marzono, R. J., Pickering, D. J., & Polluck, J. E. (2001). Classroom instruction that works: Research-based strategies for increasing student achievement. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

National Center for Learning Disabilities (2011). Learning disabilities checklist. Source is www.LD.org.

Scruggs, T. E., Mastropieri, M. A., Berkeley, S., & Graetz, J. E. (2009). “Do special education interventions improve learning of secondary content? A meta-analysis.” Remedial & Special Education, 31(6), 437-449. A summary can be retrieved from http://nichcy.org/research/summaries/abstract80.

John Carr is the founder of John Carr Educational Enterprise (JCEE, jcarrmaa.com), author of the Link of ELD-ELA Standards for California, and former lead author of the (outdated) Map of ELD-ELA Standards.