This article summarizes the first results of an ongoing experiment which tests how text-based computer games called hypertext fictions (HFs) compare to traditional reading assignments in teaching French grammar and vocabulary. My hypothesis was that interactive input is more compelling and leads to more acquisition.

The Importance of Input

The relevance of input has been well known for a long time now. One of the major theories of language acquisition is Stephen Krashen’s comprehension hypothesis (acquisition is unconscious and happens when we understand what we read or hear), which he updated with a new hypothesis called the optimal input hypothesis. Based on decades of studies, he defines input as “optimal” if it complies with four characteristics (for more details, see Language Magazine, 19(3)): it must be (1) comprehensible, (2) compelling, (3) rich, and (4) abundant.

To my knowledge, Krashen’s works mainly focus on reading books, especially on free voluntary reading, and it seems to me that there is a lack of empirical studies interrogating his new hypothesis with computer games. However, most of them provide all four elements of his list while also being interactive—which is not to be overlooked. Indeed, the interactivity allows computer games to offer an environment that is, in its own way, immersing, motivating, and stimulating—emotionally and cognitively. That is why I started this research project: could the best form of input be interactive?

Computer Games as Input Providers

Most computer games provide rich, abundant, and comprehensible input— the comprehension being supported by the context, the images, or even the possibility to interact with the virtual environment or other characters. But most of all, video games are especially interesting to us because they are very compelling. According to Krashen (see above), compelling input is “so interesting you temporarily forget that it is in another language.” In other words, it must be immersive and motivating—which is exactly what computer games are designed to be.

This ties in with Ryan and Rigby’s theory about video games’ effects on the intrinsic motivation of learners. Using their self-determination theory, they explain that, by offering learners a personalized experience—one that is unique to them and matches their choices, one that matches the consequences of their decisions—computer games create an especially immersive and motivating environment that allows learners to learn more effectively. In other words, interactivity plays a major role in learning.

Thus, it appeared to me that, by creating a fully text-based computer game with linguistic content adapted to the player’s knowledge, I could provide input that would be comprehensible, particularly rich, and abundant, while being very compelling.

Hypertext Fictions

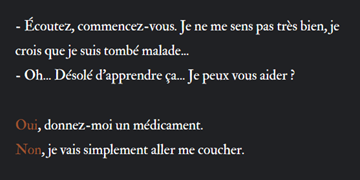

HFs are a type of interactive fiction, games that are characterized by offering a branching story in which the player is the central character: the game offers a paragraph describing a place or an action and the player alone decides how to react. Thus, every player lives a different adventure. HFs are inherently abundant in text and easy to handle: the players are presented with a text and must click on the outcome they choose. The software I used was Twine, which is free, open-source, and very easy to use.

A basic sample from my game. The player must decide between accepting help from a stranger or not.

While creating the game, I tried to stick to Plass et al.’s recommendations for game-based learning. Those are too long and technical to be developed here, so I will simply say that I paid attention to how the game motivates the player, the cognitive aspects (e.g., avoiding overloading the player with actions that are too complicated while still challenging them), the emotional aspect (e.g., provoking different types of emotions: achievement emotions, social emotions, etc.), and the sociocultural dimension (in this case, the player can create links between their reality and French culture).

The story itself is about a hiker who gets caught in a storm and must take shelter in a refuge at 3,000 meters (10,000 feet feet) above sea level. As they feel a bit sick, the other occupants start to disappear one after the other. The reader must then make the right decisions if they want to survive until dawn. There are four different endings, two resulting in the death of the player and two others where the player makes it to the end, with two different twists. Although there are only four endings, the number of possible routes is much greater, and the player-reader is made aware of this by the number of possible choices after each paragraph. The visual aspect of the game has not been neglected, as we can assume that it has an impact on the reader’s experience.

The Experiment

In this preliminary study, 28 adult Spanish students with intermediate-level French were divided into three groups (two control, one experimental) and given a 5,000-word text that exposed them to a list of specific words and grammar structures. The control groups were the Recreational Reading group (they simply had to read the text, replicating the leisure activity a learner could practice) and the Reading Assessment group (they also had to complete a reading comprehension test to replicate the homework a teacher could give). The experimental group read the hypertext fiction. All three texts were the same except for the HF, which was, of course, different for every player. However, it was designed so that every element of the list appears the exact same number of times for every participant.

Participants were presented with a vocab and grammar questionnaire before and after reading the text. The results confirmed the hypothesis: both control groups scored considerably lower than the HF group on grammar and vocabulary retention. Moreover, the HF group was the only one that didn’t lose points between questionnaires. The Recreational Reading group gained one point overall, but some of the participants lost points. The Reading Assessment group had the worst results, with 1.2 points lost overall and 60% of its participants scoring lower on the second language test.

To understand these results better, a questionnaire was sent to them about their impressions of the experiment. Of the participants from the two control groups, 88% said that the reading passage was too long and that they felt a lot of fatigue, but 65% of those who complained still found the story intriguing and even amusing.

Meanwhile, 90% of the HF group didn’t even mention being tired nor the amount of reading material. This could indicate that reading a static text for a long period caused more fatigue than an interactive one, and that, consequently, may have an impact on retention. Also, according to these results, students are more motivated, feel less fatigue, and retain more vocabulary and grammar structure when reading an interactive story.

Is Interaction Better?

From this preliminary experiment, it seems that, on the basis of the questionnaires, the interactive input was a lot more effective than traditional text. But it is also worth mentioning that the students who played the game were much more enthusiastic. Some underlined that they enjoyed the activity and loved the concept of controlling the story, making it their own. From there, we can draw the hypothesis that the interactivity is one of the reasons why they performed better—we can relate this to Krashen’s affective filter hypothesis. It is certain that their enjoyment increased their motivation to progress in the adventure, and we can presume that it encouraged more attention to the details of the story and, therefore, also to the language.

Finally, the fact of feeling less tired helps memorization. Hypertext fiction therefore seems to be the mode of reading that is both the most compelling and the one with which these students have learned the most. Of course, more research is needed to confirm the results—I’m working on it—but, meanwhile, these results are promising enough to encourage teachers to exploit hypertext fiction in the classroom to make their students read more and learn more efficiently.

References

Ryan, R. M., and Rigby, C. S. (2020). “Motivational Foundations.” In Handbook of Game-Based Learning (pp. 153–176). MIT Press.

Plass, J. L., Homer, B. D., Mayer, R. E., and Kinzer, C. K. (2020). “Theoretical Foundations of Game-Based and Playful Learning.” In Handbook of Game-Based Learning (pp. 3–24). MIT Press.

https://twinery.org

Joffrey Caron (joffrey.caron@uclm.es) is an adjunct professor and a PhD candidate at the University of Castilla–La Mancha (Spain). His fields of research include conversation analysis, SLA, and game studies.