The social isolation and countless hours of silent, independent assignments young linguistically diverse scholars have endured during the past year of online learning have left scores in dire need of lessons that affirm their identities while advancing their academic communication skills. In hopes of engaging acolytes in dual language or English language development coursework, empathetic educators often search for writing prompts that offer creative outlets for positive identity development and creative expression. Narrative assignments can certainly provide multilingual learners with unique opportunities to explore their cultural and linguistic heritages and apply language for a range of purposes. Narrative assignments focusing on multilingual experiences and cultural diversity also hold great potential within a classroom for establishing commonalities, respectfully acknowledging differences, and building community. However, well-intentioned educators frequently underestimate the complexities of crafting an effective personal narrative for learners composing in either their primary language or English as an additional language.

Unexpected Complexities of a Personal Narrative Assignment

Early in my career teaching adolescent English learners, I naively perceived a personal narrative assignment as an engaging and accessible formal writing task to launch the school term. I was under the misguided assumption that an opportunity to delve into a significant, culturally relevant experience in and of itself would activate voices and unleash writing talents. While the narrative prompt surely appeared less intimidating to my language development charges than a text-dependent informative essay, the lackluster prose they produced illustrated my profound instructional naivete.

Standards-aligned personal narrative assignments in upper-elementary and secondary coursework entail far more than the simple stories anticipated in primary grades. In fact, in many ways, a compelling personal narrative requires considerably more linguistic dexterity and organizational prowess than an opinion or informative text assignment—that is, when students are allowed in initial practice assignments to draw upon relevant background information and experiences rather than course reading material. To illustrate, a fail-safe introductory opinion paragraph prompt I have utilized with novice and long-term English learners alike is the following: Are animals capable of demonstrating any common human emotions? Construct an opinion paragraph, including a topic sentence that states your claim, appropriate transitions, a convincing reason, and a relevant example. Draw from your personal experience or background information. From an English language proficiency standpoint, taking a stance on whether a family pet or wild animal can experience a familiar human emotion such as joy or jealousy is less challenging than crafting a compelling narrative, real or imagined. Prior to assigning this prompt, I have built related schema with an accessible article from the Scholastic News magazine (Jan. 5, 2015, fifth grade) highlighting studies that document evidence of domesticated and wild animals displaying what researchers perceived as empathy, excitement, and jealousy.

After completing the text, I have engaged students in small-group and unified-class discussion of incidences they have witnessed or heard about and supported their verbal contributions with response frames and nouns naming emotions they could later leverage while independently drafting. For this initial opinion paragraph assignment, I have also provided students with a topic sentence frame to ease them into writing an effective claim, drawing key words from the prompt: Animals are quite capable of (demonstrating, experiencing) _ the common emotion _. Equipped with a manageable tool kit of appropriate transitions (e.g., for example, in addition, furthermore, for these reasons), a bank of precise topic words (e.g., fear, pride), and a paragraph exemplar to analyze as a class and emulate, even reticent second-language writers are able to construct a competent response.

Guiding English learners in drafting a related personal narrative has proved more linguistically challenging. To describe a memorable experience witnessing an animal displaying an emotion, a skillful writer consciously deploys a sophisticated range of word choices, cohesive devices, and sentence structures. A coherently organized narrative includes temporal words and phrases to signal event order like from then on and eventually that are more challenging for novice English learners than familiar transitions used in oral language and simple narratives like first, next, after, and then. Additionally, a compelling narrative is likely to incorporate carefully selected, vivid, and memorable dialogue to show characters’ reactions to situations. Even more linguistically daunting for English learners, teachers are apt to assess final work with a laser-like focus on strong word choices and artful phrasing that make the experience come to life. By far the most elusive aspect of composing an effective personal narrative for a novice English writer is the conclusion, which unlike that of a simple story should achieve two distinct goals:

1) logically concluding the sequence of events; and

2) reflecting as the narrator on what was actually learned, gained, or resolved.

Ineffective Instructional Responses to Disappointing Personal Narratives

Years of supporting English learners in grades 4–12 to successfully transition from the routine journal and simple story assignments of primary and newcomer coursework to grade-level, standards-aligned assignments like personal narratives have deepened my understanding of the conscientious planning and intentional instruction these students deserve. Simple teacher recommendations like “Try to capture your reader’s attention with vivid description in your final draft” ring hollow to a striving reader with profound English vocabulary voids.

A detailed single-score holistic rubric designed by and for teachers as a common assessment tool is also highly unlikely to illuminate this striving second-language reader and set him on a productive pathway to revision. Former ninth- and tenth-grade students, all long-term English learners, in a college readiness class for first-generation students memorably described for me the confusion and utter bewilderment they experienced receiving different holistic rubrics from core content-area teachers, all equally uninterpretable and seemingly written in yet another foreign language. Moreover, relying solely upon a classmate who also happens to be a long-term English learner to provide productive, actionable feedback for revision and editing seems at once naive, unfair, and indefensible.

Evidence-Based Directives in Developing English Learner Writing Proficiency

Current research on teaching academic content and writing to English learners in intermediate and secondary grades points to the need for explicit guidance and targeted language supports to help students move from information presented in a graphic organizer to writing sentences, and from writing sentences to composing paragraphs. Additionally, planned and interactive examination of exemplar texts must undergird units of study in informative, argumentative, and narrative writing. Schleppegrell (2017) advocates for such “genre-based” writing instruction for English learners at all levels of English proficiency to ensure they comprehend the organizational features and language forms characteristic of distinct academic writing types.

Another key finding is that formal writing assignments should be anchored in content, particularly informative and argument prompts, and that prewriting lessons should integrate intentional, interactive oral and written language instruction in priority vocabulary, sentence structures, and grammatical forms students can later leverage in formal assignments (What Works Clearinghouse, April 2014, NCEE 2014-4012).

Of equal importance, English learners benefit from an asset-based approach to curriculum and instruction, integrating well-designed materials that capitalize on students’ diversity (NASEM, 2018) while affording them carefully executed opportunities to reflect on their linguistic journeys as they build advanced language, literacy, and critical thinking skills (Bucholtz et al., 2014).

Preparing to Implement a Personal Narrative Unit with English Learners

A successful personal narrative unit incorporating English language development hinges on conscientious preparation. Prior to assigning a prompt, careful consideration should be devoted to the resources at your discretion to guide text analysis and highlight the genre’s novel features. Experience has shown me that the prompts and exemplars provided by ELA curriculum publishers are frequently unwieldy, irrelevant, or devoid of intent to promote positive identity development. Even if I manage to locate an accessible exemplar, I have not found it beneficial to devote class time to extensive analysis of a personal narrative text that is completely unrelated to the specific prompt I intend to assign.

English learners invariably fail to see the connection, and the unrelated narrative model lacks precise topic words, suitable transitions, and phrasing for the reflective conclusion they might repurpose. Similarly, the English Department rubric aligned to state writing standards requires more than modest tinkering to become a productive teaching tool within an English language development context. Moreover, ELA prompts that dovetail with an assigned literary selection are rarely preceded by language-building lessons for English learners addressing the vocabulary, syntactic structures, and grammatical forms demanded by the assignment. Prior to assigning an introductory personal narrative prompt, I recommend collaborating with colleagues on these six aspects of curriculum development. To illustrate each step, I offer and expand upon resources I have designed, field tested with teacher partners, and found highly impactful.

- Write an appropriate, relevant, and high-interest prompt

- Prepare a clear definition of the academic writing type

- Identify, adapt, or design a student-friendly analytic scoring guide

- Identify, adapt, or write an appropriate exemplar text

- Determine language priorities for exemplar analysis and instruction

- Design a prewriting discussion guide with relevant language supports

Step 1: Write an Effective Personal Narrative Prompt

When assigning a prompt to an English learner, it makes sense to follow a complexity progression, in terms of both the organizational demands and the level of personal introspection warranted by the topic. In my ELD classroom experience with English learners in middle and high school, students from diverse backgrounds have displayed varying degrees of comfort discussing issues and experiences related to their family dynamics, their journeys to the U.S., or their processes of understanding and acclimating to new cultural mores.

Mindful that a personal narrative prompt requires more reflection and disclosure than an informative or argument writing prompt, I have found it beneficial to introduce English learners to this genre with one or two relatively benign topics addressing universal experiences like receiving a special gift or teaching someone how to do something. Although I intend to segue to topics that encourage critical examination of their multilingual histories, more neutral initial prompts place the focus on understanding the structural and linguistic features of the writing type. Once students have had a dry run with less subjective prompts, they seem better poised to transition to prompts requiring greater introspection, identity analysis, and linguistic complexity.

I also recommend assigning prompts that are more detailed and explicit than a single provocative question or declarative statement. One reason is that English learners have often been assigned an array of one-sentence prompts for informal quick-writes in previous schooling, such as “Write about your favorite holiday memory” or “What superhero would you like to be?” We want to clearly signal that the assignment warrants more than a journal-entry response while helping them understand the formal prompt expectations. In addition, prompts on English language proficiency and state assessments tend to be rather lengthy, so English learners benefit from learning how to navigate a multisentence prompt.

For a formal assignment, I advise designing a three- to four-sentence prompt that accomplishes the following: 1) builds background; 2) prompts reflection; and 3) provides clear directions for writing. The sample prompts below illustrate this principle.

Sample Introductory Prompts Focused on Universal Experiences

- Recent studies have shown that animals and humans share some common emotions, such as joy, pride, sadness, and jealousy. Think about a time when you observed a household pet or wild animal demonstrating a human emotion. Write a personal narrative describing what happened and how it helped shape your views about animal feelings.

- A personal possession like a framed picture, a wristwatch, or a book may have monetary value, sentimental value, or both. What is one of your most precious childhood possessions? Write a personal narrative describing how you obtained this item, how you felt and reacted when you received it, and the reason you cherish it.

- Describe a childhood event when you did something to make your family particularly proud of your behavior or accomplishment. Perhaps you improved your grades, assisted someone in need, won an award, or learned how to play a musical instrument. Write a personal narrative describing what you did to make your family appreciate and recognize your actions.

Sample Prompts Addressing Multilingual Learner Assets and Experiences

- Being multilingual can be beneficial at home, at school, at work, and in our social lives. Switching from one language to another while communicating with others is both a skill and an advantage. Write a personal narrative describing a recent experience in which you utilized two languages to accomplish a goal, handle a difficult situation, assist a person in need, or connect meaningfully with someone.

- In different cultures and communities, families pay tribute to loved ones who have passed away with special rituals. Families may also honor relatives or community members who are still living, perhaps on the occasion of a milestone birthday or anniversary. Write a personal narrative describing how you honored and celebrated someone special in your life such as your parents, grandparents, or a teacher.

- Our formal given names and our informal nicknames often have special significance. Perhaps you were given your name to honor the legacy of a relative or highlight your unique talent, appearance, or character. Write a personal narrative describing the origin of your given name or a nickname you earned from a family member, classmate, or friend.

- Our given names and nicknames may have personal, familial, or cultural significance. These formal and informal names can also be the source of positive and negative memories. Write a personal narrative describing a time you had a positive or negative experience due to your name, including how you reacted, felt, and possibly learned an important lesson.

Step 2: Prepare a Clear Definition of the Writing Type

Many English learners, novice and long-term alike, are apt to approach a personal narrative prompt with comprehension gaps regarding the essential elements of the writing type.

It is therefore imperative to present an accurate yet accessible definition, one suitable for their age, level of English proficiency, and literacy skills. I offer the following definitions as examples from my ELD practice, the first pitched at an entry point for a younger or emergent speaker with basic English literacy skills, the second more detailed and nuanced for an adolescent English speaker and reader at intermediate to advanced proficiency.

Definition for Novice English Learners

What Is a Personal Narrative?

A personal narrative tells a story about a person’s true experience.

The beginning introduces the characters and the topic.

The middle gives details about the events in the order they happened.

The end summarizes the important details.

Sample Narrative Definition for Intermediate–Advanced English Learners

A personal narrative tells a story from the writer’s life and explains how his or her life changed as a result.

- Introductory sentences identify the context, characters, and purpose of the narrative.

- Detail sentences tell the most important events of the story.

- Transition words or phrases help move the reader through the events.

- Descriptive language, such as action verbs, precise adjectives, and adverbs, make the story more vivid and interesting.

- Concluding sentences explain how the event ended and the importance of the story, what the writer learned, gained, or resolved.

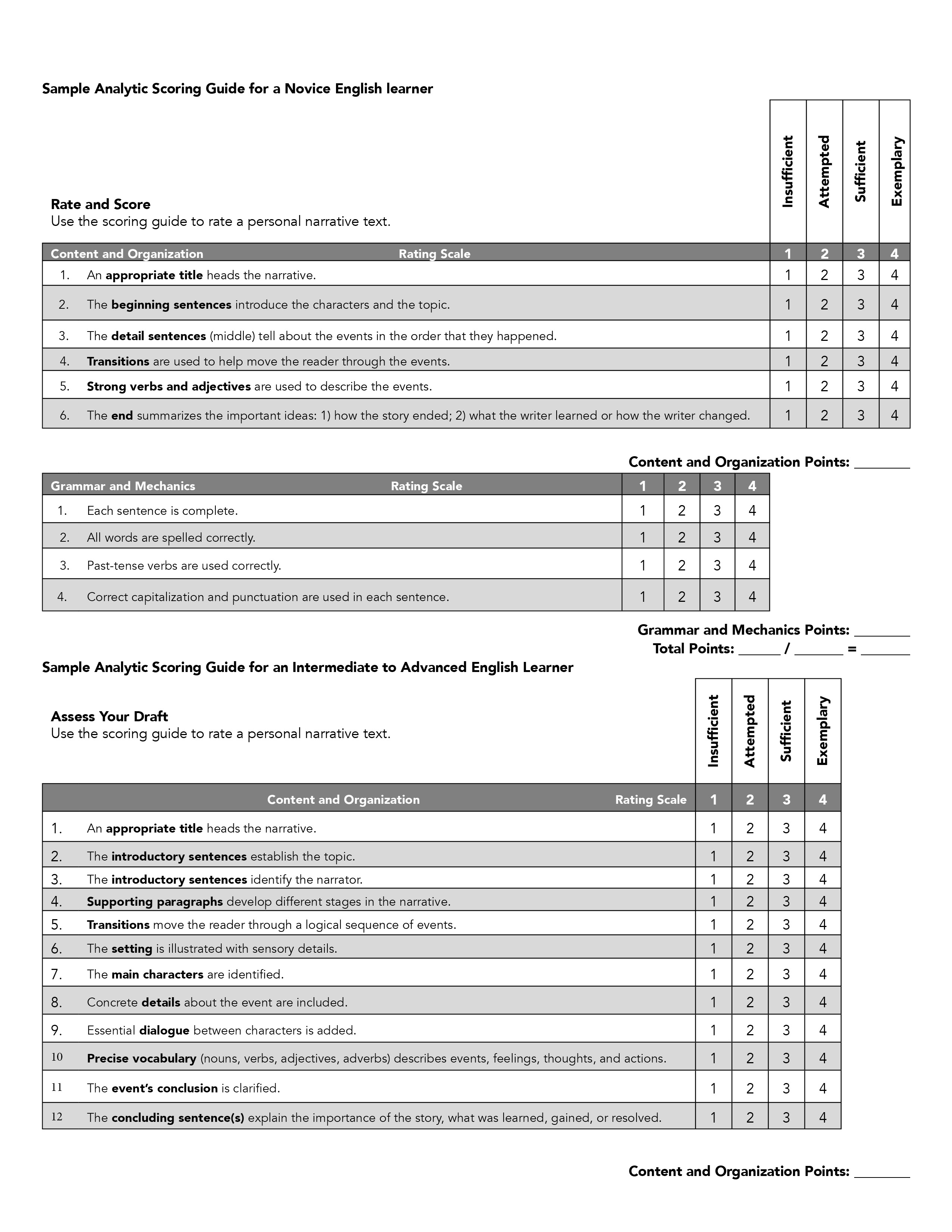

Step 3: Prepare a Student-Friendly Analytic Scoring Guide

An appropriate scoring guide is an essential tool in teaching and assessing English learner writing. Drawing from extensive experience as an ELD instructor, curriculum author, and researcher, a standard single-score holistic rubric designed for teacher use is not the most suitable instrument to place in the hands of either current or former English learners at any grade level. A conventional personal-narrative holistic rubric includes a tome of sophisticated descriptors intended for an adult, professional reader, on a proficiency sale of 1–4, for the genre’s distinct assessment categories: focus/setting; organization/plot; narrative techniques; language use. A neophyte English speaker and reader will undoubtedly find limited to no value in descriptors of the genre’s organizational features like the following: “uses temporal words, phrases, and clauses to manage the sequence of events in a logical progression”; “provides a thoughtful sense of closure from the narrated experience.”

I am an ardent proponent of analytic scoring guides. I purposefully utilize the term scoring guide with English learners rather than rubric, pointing out that I use a rubric with colleagues to compare student work and make decisions about instructional needs and course placement. For my own ELD teaching purposes, however, I provide English learners with a manageable and clearly worded assessment tool to support my instruction for a specific writing type and their student learning. An analytic scoring guide, like those provided below, is a customized teaching and assessment tool that identifies the essential elements of the writing type and allows the reader to assign a separate score to each element.

In contrast, a holistic instrument, designed for summative assessment purposes, assigns a single overall score to a piece of student writing for placement, reclassification, and comparison purposes. If a second-language writer continually receives a disappointing holistic score of one or two from a teacher, it isn’t clear from the dizzying array of rubric descriptors where to focus revision efforts in future work.

An analytic scoring guide is a nimble tool for teacher and peer formative feedback, ideally separating content and organization from grammar and mechanics so English learners can readily comprehend their specific strengths and areas in need of more careful attention. An additional attribute of an analytic scoring guide is that a few items may be weighted more heavily in the final summative assessment, such as use of effective transitions or correct past-tense verb forms, if instructional time has been devoted to these genre features.

Students can be notified that these elements will count for twice as many points, that is eight instead of four, as their personal narrative is scored and graded. Moreover, because an analytic scoring guide spells out the genre features so carefully, it greatly facilitates analysis, discussion, and guided text marking of a writing exemplar.

Step 4: Prepare a Writing Exemplar with Marking Tasks and Frames

Based on consistent feedback from former students, whether in secondary or college ELD coursework, the most valuable writing instruction they received was analysis and marking of an exemplar that met the assignment expectations. The challenge is identifying an exemplar that is not only on topic but also suitable for learners within a specific English proficiency range. Because a relevant exemplar is such a pivotal teaching and learning tool, I advise composing a suitable model or adapting a piece of former student writing. If I devote time to writing an exemplar text for a more advanced ELD cohort, I can easily modify it for learners approaching the task at earlier stages of English proficiency. Optimally, colleagues can collaborate on identification and development of appropriate exemplars for prompts that will become curricular mainstays. Once students have submitted final work, these compositions can be archived with permission and adapted to serve as models or drafts for practice revising and editing.

Along with an assignment exemplar, students benefit immensely from a set of marking tasks and response frames to guide reading, discussion, and text marking. When the exemplar is merely projected on a screen, students lack a tangible resource to interact with and return to for precise language choices and review of correct grammatical forms. A familiar set of marking tasks and response frames can be repurposed as students read and offer feedback on each other’s drafts.

Introductory Prompt and Exemplar

Think about a time you helped someone feel like they belonged. Perhaps it was a student from another city or country entering your class mid-year, a neighbor settling in to a new home, or an athlete who didn’t know any of the other teammates or much about the sport. Write a personal narrative describing what happened, what you learned, or how it changed your relationship.

Helping Someone Belong

When I was in fifth grade, a new student named Gaby joined our class right after the Thanksgiving holiday. Her family had recently moved to the U.S. from Guatemala. Before class, my teacher, Mr. Sloan, asked me if I could be Gaby’s peer ambassador for the week. At that time, I was happy to help a new student who also spoke Spanish, but I didn’t realize that she would become my lifelong friend. At the beginning of class, she looked as frightened as a kitten who had been chased up a tree by an unleashed big dog.

Mr. Sloan sat her down next to me and handed her a folder, text, and pencil case. She kept staring at the supplies and seemed frozen stiff, so I tried to imagine ways I could help her feel more comfortable.

First, I told her to tap my shoulder whenever she felt confused or afraid. Next, I assured her that I would be happy to whisper to her in Spanish whatever she needed to do. At early recess time, I took her gently by the hand and introduced her to a few nice classmates who also spoke Spanish.

Then, they invited us to join them in playing four square, but that was a new game for Gaby so I tried to carefully explain the rules. She turned out to be an impressive athlete who quickly caught on. She even beat the rest of us during lunchtime recess! When the bell rang and we returned to the classroom, she looked so much more relaxed and confident. After school, I told Mr. Sloan that I would be happy to be Gaby’s helper for as long as she needed support.

Now Gaby and I are in seventh grade, and we have become very close friends. We share interests in coding and music besides planning to go to college. Because we both moved to the U.S. from Central America, we are committed to helping new immigrant students feel welcome in our school, just as I did for Gaby in fifth grade.

Text Marking and Discussion Tasks Mark the narrative text elements. Then discuss them with your partner.

- Circle the characters’ names. (One, another) character is ___.

- Underline the setting. The narrative takes place (at, in) ___.

- Double underline the topic of the story. The narrative is about ___.

- Draw a box around transition words or phrases. (One, another) transition is ___.

- Number (1–4) events of the narrative. The (first, second, next, following, final) __ event in the narrative is ___.

- Star four precise words that made the writing more vivid. An example of a precise (noun, verb, adjective, adverb) is ___.

- Put parentheses around the ending of the story. The ending is that ___.

- Put brackets around the importance of the story. The importance is that ___.

Step 5: Determine Language Priorities for Exemplar Analysis and Instruction

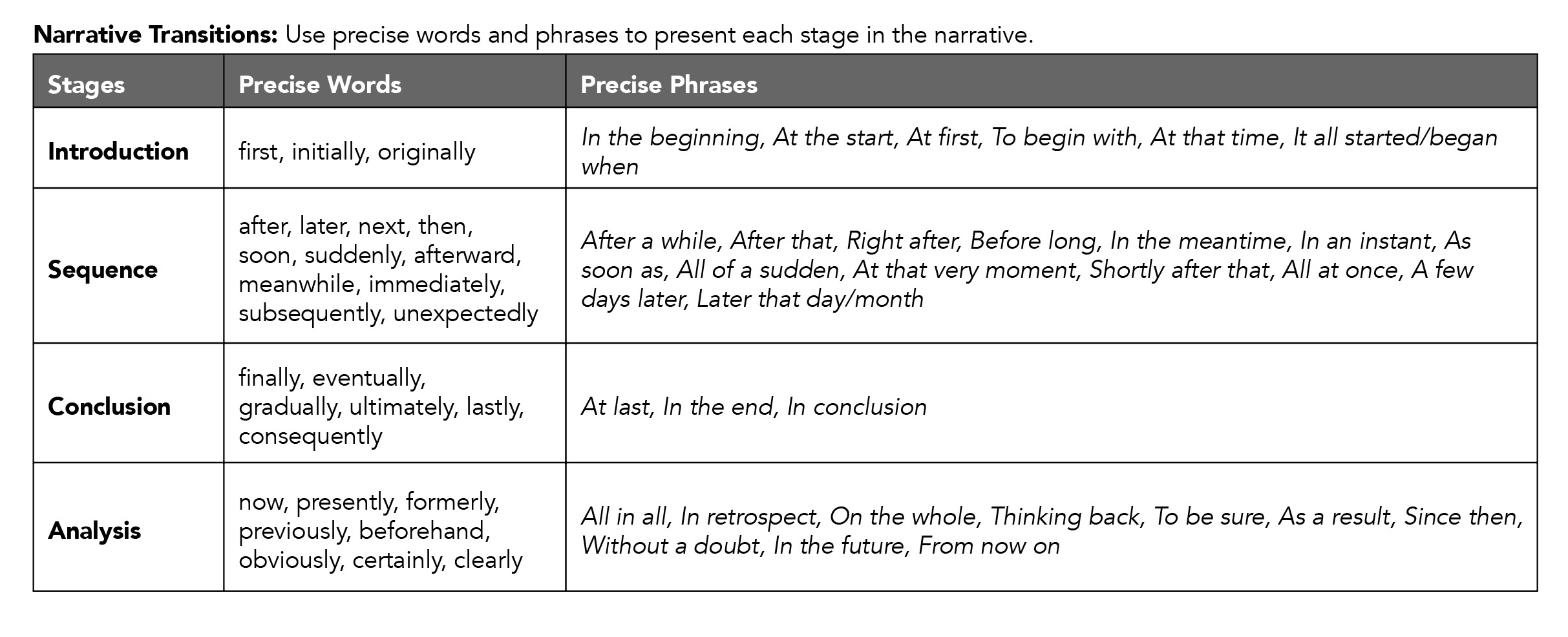

An effective personal narrative requires agility with a range of vocabulary and cohesive devices. An introductory narrative language tool kit should include appropriate transitional devices to logically sequence the event, precise word choices to evoke characters’ thoughts and feelings related to the topic, and strong past-tense verbs to describe completed actions. The reflection component of the conclusion warrants a productive array of verbs to discuss what was learned, gained, or resolved.

I have listed a small number of language objectives relevant to personal narrative text instruction. English learners benefit from guidance in identifying language targets within an exemplar such as transitional words and phrases, correct pronoun reference, and strong verb choices.

My ELD classroom experience has convinced me of the additional need for a brief grammatical tune-up lesson on a priority grammatical target following exemplar analysis such as use of irregular past-tense verb forms to note completed actions within the narrative.

The teaching resource outlining transition words and phrases used to present the four distinct stages in a narrative provides appropriate choices to include in exemplar texts for a range of English language proficiencies. I don’t recommend distributing the resource but instead selecting suitable candidates for the students’ proficiency level to embed in exemplar texts and preparing a more manageable student reference.

Sample Personal Narrative Language Objectives: Intermediate English

- Write an introductory sentence including a precise adjective that prepares the reader for a story describing a surprising experience: surprising, unusual, unexpected.

- Use basic transition words that show the order of events: first, after, then, next, later, finally.

- Use advanced transition words and phrases that show the order of events: initially, at that time, after that moment, from then on, as time passed, eventually.

- Describe a character’s positive emotions using precise adjectives: surprised, excited, overjoyed, thrilled, delighted, proud.

- Describe a character’s completed actions using strong simple past-tense verbs ending in -ed: arrived, departed, dashed, avoided.

- Use strong present-tense verbs to describe what you have gained from an experience: understand, realize, recognize, appreciate.

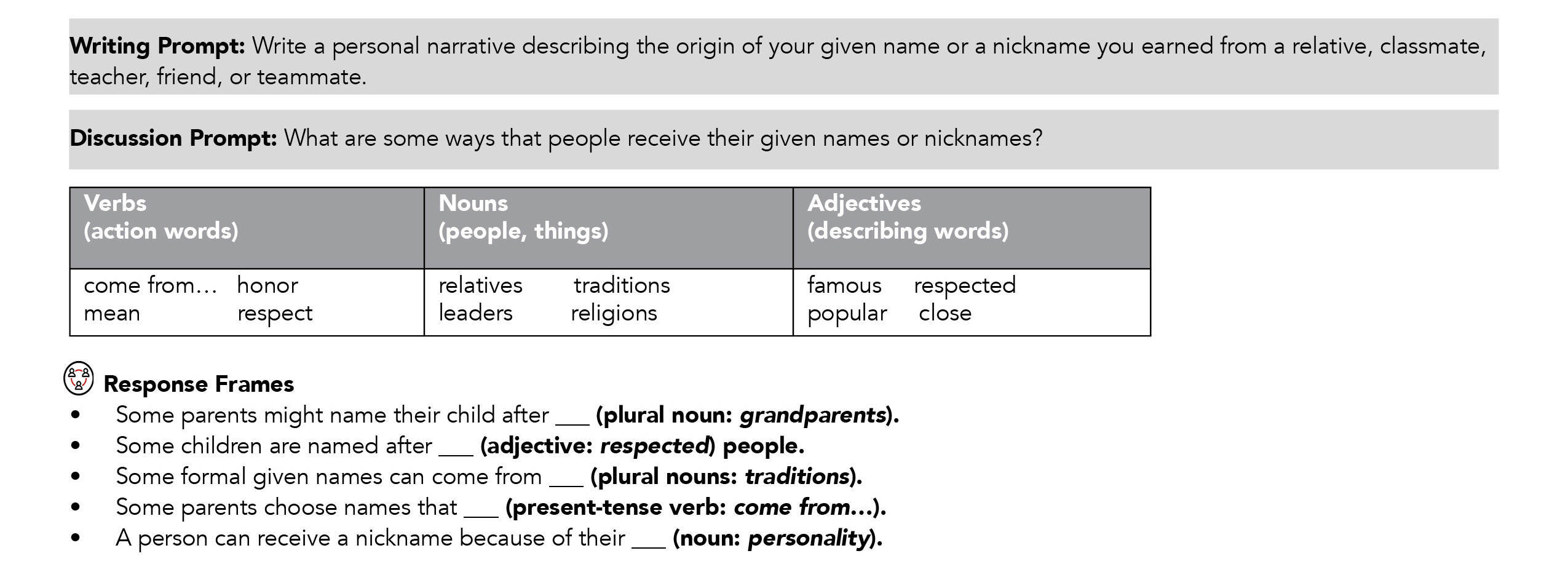

Step 6: Design a Prewriting Discussion Guide with Relevant Language Supports

Graphic tools are widely employed by teachers of English learners to help students generate and organize ideas; however, a concerted effort to expand ideation and equip students with more accurate vocabulary choices and grammatical forms for the specific writing prompt is not as commonplace. English learners reap multiple benefits from engaging in purposeful class discussions with embedded language development prior to drafting personal narratives. They can be stimulated and acknowledged by peers while also building a potent language tool kit to approach the formal writing task with more linguistic mindfulness and precision than their routine journal responses.

The following prewriting discussion is adapted from an ELD unit for multilingual learners focused on identity exploration in my recent publication Language Launch (Kinsella, 2020). The personal narrative assignment includes a targeted array of focused, interactive prewriting lessons for idea generating, vocabulary building, and grammatical awareness.

Concluding Thoughts

A well-crafted personal narrative unit holds great potential for providing multilingual learners with lessons that are thought-provoking and inclusive while advancing their spoken and written language for academic purposes. These writing assignment attributes seem all the more important for diverse learners attending virtual classes with individuals they have never met in person. As we transition to hybrid instruction, I am hoping fellow educators across the nation will devote some precious real-time instructional minutes to a personal narrative unit with more than one opportunity for multilingual learners to build their communicative competence while reflecting on their unique cultural and linguistic histories.

Kate Kinsella, EdD (drkate@drkatekinsella.com), writes curriculum, conducts K–12 research, and provides professional development addressing evidence-based practices to advance English language and literacy skills for multilingual learners. She is the author of a number of research-informed curricular anchors for English learners, including English 3D, Language Launch, and the Academic Vocabulary Toolkit.

References

Bucholtz, M., Lopez, A., Mojarro, A., Skapoulli, E., VanderStouwe, C., and Warner-Garcia, S. (2014). “Sociolinguistic Justice in the Schools: Student Researchers as Linguistic Experts.” Language and Linguistics Compass 8(4), 144–157.

Kinsella, K. (2020). English 3D: Language Launch. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

NASEM. (2018). English Learners in STEM Subjects: Transforming Classrooms, Schools, and Lives. Washington, DC. National Academies Press.

NCEE. (April 2014–4012). Teaching Academic Content and Literacy to English Learners in Elementary and Middle School. Educator’s Practice Guide/What Works Clearinghouse. Washington, DC. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance.

Schleppegrell, M. J. (2017). “Systemic Functional Grammar in the K–12 Classroom.” In Handbook of Research in Second

Language Teaching and Learning (Vol. 3), edited by Eli Hinkel. New York, NY: Routledge.