Infants and young children have brains with a linguistic superpower, according to Georgetown University Medical Center neuroscientists, who found that unlike adults who use a specific areas in one or the other of their brain’s two hemispheres to process most discrete neural tasks, young children use both the right and left hemispheres to do the same task. This may explain why children generally recover from neural injury much better than adults.

“The neural basis of language development: Changes in lateralization over age” published this month in PNAS, finds that to understand language (more specifically, processing spoken sentences), children use both hemispheres, which ties in with previous and ongoing research led by Georgetown neurology professor Elissa L. Newport, PhD, a former postdoctoral fellow Olumide Olulade, MD, PhD, and neurology assistant professor Anna Greenwald, PhD.

“This is very good news for young children who experience a neural injury,” says Newport, director of the Center for Brain Plasticity and Recovery, a joint enterprise of Georgetown University and MedStar National Rehabilitation Network. “Use of both hemispheres provides a mechanism to compensate after a neural injury. For example, if the left hemisphere is damaged from a perinatal stroke—one that occurs right after birth—a child will learn language using the right hemisphere. A child born with cerebral palsy that damages only one hemisphere can develop needed cognitive abilities in the other hemisphere. Our study demonstrates how that is possible.”

Their study solves a mystery that has puzzled clinicians and neuroscientists for a long time, says Newport.

In almost all adults, sentence processing is possible only in the left hemisphere, according to both brain scanning research and clinical findings of language loss in patients who suffered a left hemisphere stroke.

However in young children, damage to either hemisphere is much less likely to result in language deficits; language can be recovered in many patients even if the left hemisphere is severely damaged. These facts suggest that language is distributed to both hemispheres early in life, Newport says. However, traditional scanning had not revealed the details of these phenomena until now. “It was unclear whether strong left dominance for language is present at birth or appears gradually during development,” explains Newport.

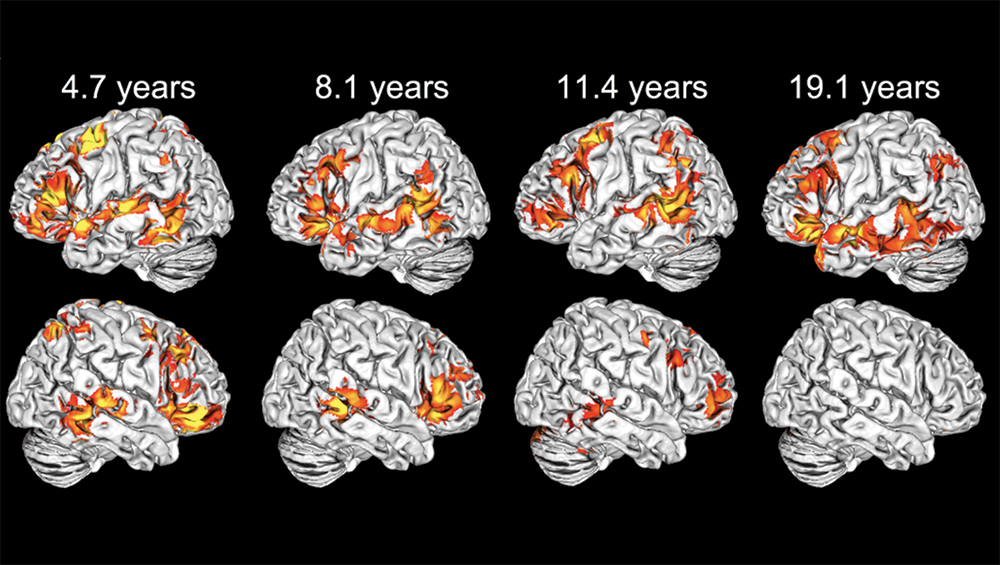

Now, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) analyzed in a more complex way, the researchers have shown that the adult lateralization pattern is not established in young children and that both hemispheres participate in language during early development.

Brain networks that localize specific tasks to one or the other hemisphere start during childhood but are not complete until a child is about 10 or 11, she says. “We now have a better platform upon which to understand brain injury and recovery.”

Researchers found that, at the group level, even young children show left-lateralized language activation. However, a large proportion of the youngest children also show significant activation in the corresponding right-hemisphere areas. (In adults, the corresponding area in the right hemisphere is activated in quite different tasks, for example, processing emotions expressed with the voice. In young children, areas in both hemispheres are each engaged in comprehending the meaning of sentences, as well as recognizing the emotional affect.)

Newport believes that the “higher levels of right hemisphere activation in a sentence processing task and the slow decline in this activation over development are reflections of changes in the neural distribution of language functions and not merely developmental changes in sentence comprehension strategies.”

She also says that, if the team were able to do the same analysis in even younger children, “it is likely we would see even greater functional involvement of the right hemisphere in language processing than we see in our youngest participants (ages four to six years old).

“Our findings suggest that the normal involvement of the right hemisphere in language processing during very early childhood may permit the maintenance and enhancement of right hemisphere development if the left hemisphere is injured,” Newport says.

The investigators are now examining language activation in teenagers and young adults who have had a major left hemisphere stroke at birth. Maybe, young multilinguals should also be researched to see if they retain language activity in the right hemisphere.