In the first installment of a two-part article, Jeff Zwiers, Susan O’Hara, and Robert Pritchard present essential shifts for teaching Common Core Standards to academic English learners

The transition to the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) offers a window of opportunity to fortify what and how we teach. It also provides a chance to reflect on how our most marginalized students most effectively learn the most difficult knowledge and skills. The CCSS challenge us to teach students much more than loosely connected pieces of knowledge and test-taking skills. They offer an opportunity to equip diverse students with deeper understandings of content, more expert thinking skills, and stronger communication skills. They offer a rare opportunity, if we seize it, to make some major shifts in moving from surface-level transmission and memorization models to approaches that richly cultivate the cognitive and communicative potentials of every student.

The CCSS have led to a wide range of interpretations for how teaching should change. These changes are usually called “shifts.” Much of the focus has been on outlining the implications of the standards for teaching all students. There has been less emphasis on identifying additional shifts that would benefit academic English learners and students who don’t do well in school. Yet the urgency of meeting their learning needs has grown as teachers and schools are seeing firsthand the more rigorous literacy and communication demands that undergird many of the new standards.

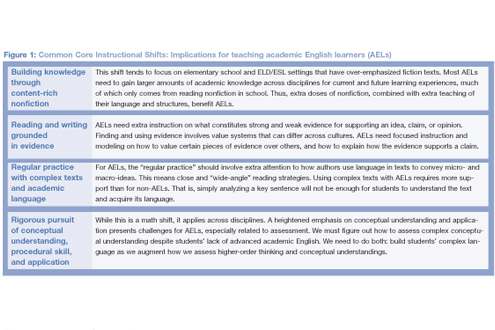

Before addressing the AEL (Academic English Learner) Shifts, the term used in this article, it is helpful to analyze the commonly cited shifts currently being suggested within the education community and consider their implications for teaching academic English learners. Several of the more better-known shifts for teaching all students are found in the first column of Figure 1. In the second column are several important implications and nuances of these shifts for teaching academic English learners.

Additional shifts

In our work with teachers and students, we have uncovered eight additional shifts (AEL Shifts) in instruction and assessment that are needed to help diverse students succeed. Many of these shifts are not new; they are just reminders of (a) practices that teachers have been using for years to make teaching and learning effective and (b) what we know we should have been doing all along in our schools. Then again, several shifts do require us to step out and take a fresh view of pedagogical habits. We describe three in this part and the remaining five in Part II.

From Access to Ownership

Plenty of professional-development resources and programs focus on providing English learners with better “access” to the content. Access tends to mean comprehension. Much of what is called sheltered instruction is focused on providing academic English learners with increased comprehension of a lesson’s content. Yet too often, sheltered instruction can involve significant watering down of complex language in order to provide easier access to texts and content, and in doing so, the sheltering fails to build students’ grade-level language and literacy.

Sheltered instruction often does achieve access, but access is not enough. We need to foster students’ ownership of the language and thinking needed to communicate complex concepts. Ownership means being able to use language and concepts in novel and authentic ways — not merely to answer questions on a test. This shift therefore focuses on supporting students in using language in ways that are valued in the discipline and at grade level.

This shift also consists of making sure academic English learners benefit from working with peers at higher and lower levels of language proficiency. This means untracking their classes and placing them in mainstream classrooms. Of course, this also means adjusting instruction so that all students are supported and have multiple interactions with peers.

In a nutshell, we need to stop sheltering students from interactions with mainstream peers, disciplinary communication experiences, and knowledge-working skills that they will need for future classes, college, and career success.

One way to not over-shelter is to use grade-level complex texts. A classroom snapshot of this is Mr. Ellis’s sixth-grade language arts class in which they are reading a challenging article on genetic engineering. They are using a visual scaffold called “wide-angle reading” (Zwiers, O’Hara, & Pritchard, 2014) to get the big picture of the text and its purposes. Students, in pairs, first survey the article and discuss the possible purposes of the author, the teacher, and the reader. They use pencil, knowing that these might change as they read. They then identify the type of text, text structure, thinking skills needed, organization strategies, questions, and key terms, all of which provide a framework for supporting the complex ideas that emerge in the text. At times, Mr. Ellis zooms in to ask a few close-reading questions about key parts of the article.

Here are several suggestions for implementing this shift:

• Use grade-level texts and intellectually challenging tasks with the appropriate linguistic supports for all learners, and have students engage in both close and wide-angle reading practices (See Zwiers, O’Hara, & Pritchard, 2014).

• Engage in a range of text-based writing and conversation activities in which students are supported in using language and ideas from the texts.

• Have students work in heterogeneous groups and classrooms on text-based tasks.

• Provide opportunities for students to use technology to communicate original ideas and messages.

• Inspire, allow, and support students to come up with their own questions, own answers, own ideas, own evidence, own syntheses, own comparisons, own opinions, own problems, and own texts.

From Pieces to Wholes

One of the most damaging effects of multiple-choice-test-pointed instruction is the focus on many disjointed “pieces” of content knowledge and language. Students attend classes that are not integrated, read textbooks that jump from topic to topic, and take tests full of unrelated short texts and questions. Academic English learners, in particular, have been asked to spend loads of time memorizing word meanings, grammar rules, math shortcuts, and a range of facts culled from long lists of standards. Parts and pieces are easier and cheaper to test, to teach, and to learn. This focus on quantity, rather than quality, considers learning to be the accumulation of discreet facts, word meanings, and grammar rules. “The more accumulation, the better,” some say. This shift, however, emphasizes helping students to put pieces together for a purpose and to use increasingly advanced levels of academic discourse skills to create and communicate original and useful whole ideas in a discipline.

A close cousin of this shift is moving from a focus on short, right answers to a focus on longer, more complex understandings. Students have spent too much time thinking of language as choosing the right answer. This shift encourages students to go beyond picking or knowing right answers to actually using the answers in the construction and communication of a complex idea in the discipline. Many students are yearning for chances to do less choosing, listing, and regurgitating of the pieces of other people’s ideas. They desire to do more creating, sculpting, arguing, and shaping of whole ideas. Fortunately, the new standards emphasize putting ideas together, using critical thinking skills, collaborating, communicating, and doing tasks that better prepare students for the complex tasks of the future.

A classroom snapshot of this shift is Ms. Bernard’s fourth-grade math class. She models with another student how to approach a real problem she has that involves fractions, how to estimate the answer, and how to represent what is happening in different ways. She then has her students practice explaining to one another why they used certain strategies and how they got their answers. She finally has them pair up to create their own real-world problems and write out how to solve them. She puts many of their problems on quizzes and tests.

Here are several suggestions for implementing this shift:

• Provide more authentic and engaging purposes for learning with project-based learning and performance-based assessments. These give students reasons to come to school, to learn toward something, and to work to put the pieces together in order to construct and communicate complex ideas.

• When teaching reading, don’t dive straight into a text to focus on vocabulary or individual sentences without helping students look at the text’s purposes, main ideas, structures, and other big picture, wide-angle dimensions.

• In language arts classes, use whole novels; across all content areas, use whole articles and a variety of complete complex texts.

From Content to Language, Literacy, and Content

This shift is based on a somewhat extreme point of view: complex language and literacy skills that can be learned in each content area are as important as the content itself. We do not dispute that students need to know a discipline’s facts, concepts, and skills in order to learn. Indeed, academic English learners often need more school-valued content knowledge than their peers who are more proficient in academic English. Yet this doesn’t mean that we should reduce language and literacy demands in order to focus on content. Rather, and this is somewhat counterintuitive, we must realize the large roles that language and literacy play in content learning. We must develop our PLK (Bunch, 2013; Zwiers, 2008), or pedagogical language knowledge, which is similar to Shulman’s (1987) pedagogical content knowledge, or PCK. Teachers need to know the language that is running the learning show in each lesson. The more we develop students’ language and literacy skills needed for learning, the better all students will learn the content in enduring ways. And vice versa.

A classroom snapshot of this shift is Mr. Wilson’s ninth-grade science class. He not only wants students to be able to balance chemical equations, but he also wants them to be able to clearly explain, using scientific language, how and why the changes occur. He models his thinking and highlights the language that he has used, such as “According to the law of conservation of mass, if…, then…” He listens for use of this language and other expressions that show attempts to clarify what is happening in the chemical reactions. While observing students working in pairs, he jots down student uses of language to highlight afterward. For example, one student said, “Because we need to have the same number of atoms in the product, we need to put a coefficient of 2 here in front of N2.” Mr. Wilson then used this as a model of starting sentences with “because.”

Here are several suggestions for implementing this shift:

• Work with a literacy and/or English language development specialist to identify the challenging background knowledge and language demands in the texts that you teach, and discuss strategies for addressing these demands.

• Create language objectives and disciplinary literacy objectives that help remind you of the types of language and literacy skills needed by students to learn and show learning.

• Plan with language, literacy, and content learning in mind. When you plan lessons and units, have a clear vision of where you want students to move with respect to language and literacy development.

• Formatively assess students’ language of the discipline by analyzing their writing and listening to their conversations in response to cognitively demanding prompts.

• Balance the focus on oral and written uses of language in support of content learning.

Each of these shifts is a continuum. How far along a teacher or school is in each shift on any given day will vary. In fact, many teachers have already been shifting in these ways since well before the CCSS were introduced. This is what effective teachers do. They learn from successes, mistakes, resources, students, conversations, professional development, and so on. They know what their students need, and they shift and adapt. But we need to keep growing: every teacher and school can improve in one or more of the shifts described above and the five shifts to be described in the next installment of this article.

The complexity of teaching is profound, and students change every year. Academic English learners, in particular, need teachers at the top of their game in knowing what and how to teach in the limited windows of time given. True, it’s messy and challenging to shift away from the familiar, but our students’ futures are in the balance.

References

Cazden, C. (2001). Classroom discourse: The language of teaching and learning. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Bruner, J. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Bunch, G. (2013). Pedagogical language knowledge: preparing mainstream teachers for English learners in the new standards era. Review of Research in Education, 37, 2013, p. 298-341.

Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and Education. New York: MacMillan.

Freire, P. (1978). Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum Publishing Group.

Shulman, L. (1986). “Those who understand: Knowledge growth in teaching.” Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-31.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). “The genesis of higher mental functions.” In R. Reiber (Ed.), The history of the development of higher mental functions (Vol. 4, pp. 97-120). New York: Plennum.

Zwiers, J., O’Hara, S., & Pritchard, R. (2014). Common Core Standards in diverse classrooms: Essential practices for developing academic language & disciplinary literacy. Portsmouth, NH: Stenhouse.

Jeff Zwiers, PhD, is a senior researcher at Stanford University; Susan O’Hara, PhD, is executive director of CRESS, School of Education, University of California, Davis; Robert Pritchard, PhD, is professor of educational leadership at Sacramento State University. This article is adapted from Chapter 1 of Common Core Standards in diverse classrooms: Essential practices for developing academic language & disciplinary literacy, by Jeff Zwiers, Susan O’Hara, & Robert Pritchard, (2014). Stenhouse.